Ding Li Kung-Fu

Discover contemporary artworks by Ding Li Kung-Fu, browse recent artworks and buy online. Categories: zimbabwean contemporary artists. Artistic domains: Painting. Account type: Artist , member since 2010 (Country of origin Zimbabwe). Buy Ding Li Kung-Fu's latest works on ArtMajeur: Discover great art by contemporary artist Ding Li Kung-Fu. Browse artworks, buy original art or high end prints.

Artist Value, Biography, Artist's studio:

Cresta Kungfu Wushu • 10 artworks

View allRecognition

Biography

-

Nationality:

ZIMBABWE

- Date of birth : 1982

- Artistic domains:

- Groups: Zimbabwean Contemporary Artists

Ongoing and Upcoming art events

Influences

Education

Artist value certified

Achievements

Activity on ArtMajeur

Latest News

All the latest news from contemporary artist Ding Li Kung-Fu

Kung fu

"Kung fu" redirects here. For other uses, see Kung fu (disambiguation).

This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters.

Part of the series on Chinese martial arts

List of Chinese martial arts

Terms

* Kung fu (功夫)

* Wushu (武術)

* Qigong (氣功)

Historical places

* Shaolin Monastery (少林寺)

* Wudang Mountains (武當山)

* Mount Emei (峨嵋山)

* Kunlun Mountains (崑崙山)

Historical people

* Five Elders (五祖)

* Yim Wing-chun / Yan Yongchun (嚴詠春)

* Hung Hei-gun / Hong Xiguan (洪熙官)

* Fong Sai-yuk (方世玉)

* Dong Haichuan (董海川)

* Yang Luchan (楊露禪)

* Wu Quanyou (吳全佑)

* Ten Tigers of Canton (廣東十虎)

* Chen Fake (陈发科)

* Chan Heung / Chen Xiang (陳享)

* Wong Fei-hung / Huang Feihong (黃飛鴻)

* Sun Lu-t'ang (孫祿堂)

* Huo Yuanjia (霍元甲)

* Yip Man / Ye Wen (葉問)

* Bruce Lee / Li Xiaolong (李小龍)

Legendary figures

* Bodhidharma / Putidamo / Damo (菩提達摩)

* Zhang Sanfeng (張三丰)

* Eight immortals (八仙)

Related

* Hong Kong action cinema

* Wushu (sport)

* Wuxia (武俠)

Mandarin- Hanyu Pinyin wǔshù

Chinese martial arts, also referred to by the Mandarin Chinese term wushu (simplified Chinese: 武术; traditional Chinese: 武術; pinyin: wǔshù) and popularly as kung fu (Chinese: 功夫 pinyin: gōngfu), are a number of fighting styles that have developed over the centuries in China. These fighting styles are often classified according to common traits, identified as "families" (家, jiā), "sects" (派, pài) or "schools" (門, mén) of martial arts. Examples of such traits include physical exercises involving animal mimicry, or training methods inspired by Chinese philosophies, religions and legends. Styles which focus on qi manipulation are labeled as internal (内家拳, nèijiāquán), while others concentrate on improving muscle and cardiovascular fitness and are labeled external (外家拳, wàijiāquán). Geographical association, as in northern (北拳, běiquán) and southern (南拳, nánquán), is another popular method of categorization.

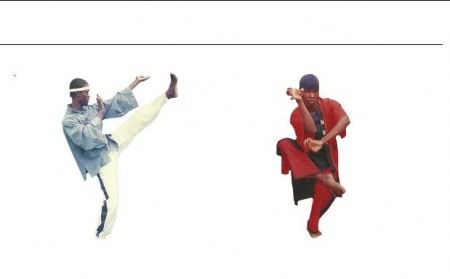

Kung fu As An Art Form

Terminology

Kung-fu and wushu are terms that have been borrowed into English to refer to Chinese martial arts. However, the Chinese terms kung fu (Chinese: 功夫; pinyin: gōngfū) and wushu (simplified Chinese: 武术; traditional Chinese: 武術; pinyin: wǔshù About this sound listen (Mandarin) (help·info); Cantonese: móuh-seuht) have distinct meanings;[1] the Chinese literal equivalent of "Chinese martial art" would be Zhongguo wushu (traditional Chinese: 中國武術; pinyin: zhōngguó wǔshù).

Wǔshù literally means "martial art". It is formed from the two words 武術: 武 (wǔ), meaning "martial" or "military" and 術 (shù), which translates into "discipline", "skill" or "method."

The term wushu has also become the name for modern sport of wushu involving the performance of Chinese bare-handed and weapons forms (Chinese: 套路, pinyin: tàolù) adapted and judged to a set of contemporary aesthetic criteria for points developed since 1949 in the People's Republic of China.[2][3]

The term "kung fu"

In Chinese, kung fu can also be used in contexts completely unrelated to martial arts, and refers colloquially to any individual accomplishment or skill cultivated through long and hard work.[1] Wushu is a more precise term for general martial activities.

History

The genesis of Chinese martial arts has been attributed to the need for self-defense, hunting techniques and military training in ancient China. Hand-to-hand combat and weapons practice were important in training ancient Chinese soldiers.[4][5]

Ancient depiction of fighting monks practicing the art of self-defense.

According to legend, Chinese martial arts originated during the semi-mythical Xia Dynasty (夏朝) more than 4,000 years ago.[6] It is said the Yellow Emperor Huangdi (legendary date of ascension 2698 BCE) introduced the earliest fighting systems to China.[7] The Yellow Emperor is described as a famous general who, before becoming China’s leader, wrote lengthy treatises on medicine, astrology and the martial arts. He allegedly developed the practice of jiao di and utilized it in war.[8]

Early history

Shǒubó (手搏), practiced during the Shang dynasty (1766–1066 BCE), and Xiang Bo (similar to Sanda) from the 7th century BCE,[9] are two examples of ancient Chinese martial arts. In 509 BCE, Confucius suggested to Duke Ding of Lu that people practice the martial arts as well as the literary arts[9]; thus, martial arts began to be practiced by laypeople outside the military and or religious sects. A combat wrestling system called juélì or jiǎolì (角力) is mentioned in the Classic of Rites (1st century BCE).[10] This combat system included techniques such as strikes, throws, joint manipulation, and pressure point attacks. Jiao Di became a sport during the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE). The Han History Bibliographies record that, by the Former Han (206 BCE – 8 CE), there was a distinction between no-holds-barred weaponless fighting, which it calls shǒubó (手搏), for which "how-to" manuals had already been written, and sportive wrestling, then known as juélì or jiǎolì (角力). Wrestling is also documented in the Shǐ Jì, Records of the Grand Historian, written by Sima Qian (ca. 100 BCE).[11]

A hand to hand combat theory, including the integration of notions of "hard" and "soft" techniques, is expounded in the story of the Maiden of Yue in the Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue (5th century BCE).[12]

In the Tang Dynasty, descriptions of sword dances were immortalized in poems by Li Bai. In the Song and Yuan dynasties, xiangpu (a predecessor of sumo) contests were sponsored by the imperial courts. The modern concepts of wushu were fully developed by the Ming and Qing dynasties.[13]

Philosophical influences

The ideas associated with Chinese martial arts changed with the evolution of Chinese society and over time acquired some philosophical bases: Passages in the Zhuangzi (庄子), a Daoist text, pertain to the psychology and practice of martial arts. Zhuangzi, its eponymous author, is believed to have lived in the 4th century BCE. The Tao Te Ching, often credited to Lao Zi, is another Daoist text that contains principles applicable to martial arts. According to one of the classic texts of Confucianism, Zhou Li (周禮/周礼), Archery and charioteering were part of the "six arts" (simplified Chinese: 六艺; traditional Chinese: 六藝; pinyin: liu yi, including rites, music, calligraphy and mathematics) of the Zhou Dynasty (1122–256 BCE). The Art of War (孫子兵法), written during the 6th century BCE by Sun Tzu (孫子), deals directly with military warfare but contains ideas that are used in the Chinese martial arts.

Daoist practitioners have been practicing Tao Yin, physical exercises similar to Qigong that was one of the progenitors to Tai Chi Chuan, from at least as early as 500 BCE.[14] In 39–92 CE, "Six Chapters of Hand Fighting", were included in the Han Shu (history of the Former Han Dynasty) written by Pan Ku. Also, the noted physician, Hua Tuo, composed the "Five Animals Play"—tiger, deer, monkey, bear, and bird, around 220 BCE.[15] Daoist philosophy and their approach to health and exercise have influenced the Chinese martial arts to a certain extent. Direct reference to Daoist concepts can be found in such styles as the "Eight Immortals" which uses fighting techniques that are attributed to the characteristics of each immortal. [16]

Shaolin and temple-based martial arts

Main article: Shaolin Monastery

The Shaolin style of wushu is regarded as the first institutionalised Chinese martial art.[17] The oldest evidence of Shaolin participation in combat is a stele from 728 CE that attests to two occasions: a defense of the Shaolin Monastery from bandits around 610 CE, and their subsequent role in the defeat of Wang Shichong at the Battle of Hulao in 621 CE. From the 8th to the 15th centuries, there are no extant documents that provide evidence of Shaolin participation in combat. However, between the 16th and 17th centuries there are at least forty sources which provide evidence that not only did the monks of Shaolin practice martial arts, but martial practice had become such an integral element of Shaolin monastic life that the monks felt the need to justify it by creating new Buddhist lore.[18] References of martial arts practice in Shaolin appear in various literary genres of the late Ming: the epitaphs of Shaolin warrior monks, martial-arts manuals, military encyclopedias, historical writings, travelogues, fiction and poetry. However these sources do not point out to any specific style originated in Shaolin.[19] These sources, in contrast to those from the Tang period, refer to Shaolin methods of armed combat. This include a skill for which Shaolin monks had become famous—the staff (gùn, Cantonese gwan). The Ming General Qi Jiguang included description of Shaolin Quan Fa (Pinyin romanization: Xiao Lin Quán Fǎ or Wade-Giles romanization Shao Lin Ch'üan Fa, 少 林 拳 法 "fist principles"; Japanese pronunciation: Shorin Kempo or Kenpo) and staff techniques in his book, Ji Xiao Xin Shu (紀效新書), which can be translated as "New Book Recording Effective Techniques". When this book spread to East Asia, it had a great influence on the development of martial arts in regions such as Okinawa [20] and Korea.[21]

The modern era

The fighting styles that are practiced today were developed over the centuries, after having incorporated forms that came into existence later. Some of these include Bagua, Drunken Boxing, Eagle Claw, Five Animals, Hsing I, Hung Gar, Lau Gar, Monkey, Bak Mei Pai, Praying Mantis, Fujian White Crane, Wing Chun and Tai Chi Chuan.

In 1900-01, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists rose against foreign occupiers and Christian missionaries in China. This uprising is known in the West as the Boxer Rebellion due to the martial arts and calisthenics practiced by the rebels. Though it originally opposed the Manchu Qing Dynasty, the Empress Dowager Cixi gained control of the rebellion and tried to use it against the foreign powers. The failure of the rebellion led ten years later to the fall of the Qing Dynasty and the creation of the Chinese Republic.

The present view of Chinese martial arts are strongly influenced by the events of the Republican Period (1912–1949). In the transition period between the fall of the Qing Dynasty as well as the turmoils of the Japanese invasion and the Chinese Civil War, Chinese martial arts became more accessible to the general public as many martial artists were encouraged to openly teach their art. At that time, some considered martial arts as a means to promote national pride and build a strong nation. As a result, many training manuals (拳谱) were published, a training academy was created, two national examinations were organized as well as demonstration teams travelled overseas,[22] and numerous martial arts associations were formed throughout China and in various overseas Chinese communities. The Central Guoshu Academy (Zhongyang Guoshuguan, 中央國術館/中央国术馆) established by the National Government in 1928[23] and the Jing Wu Athletic Association (精武體育會/精武体育会) founded by Huo Yuanjia in 1910 are examples of organizations that promoted a systematic approach for training in Chinese martial arts.[24][25][26] A series of provincial and national competitions were organized by the Republican government starting in 1932 to promote Chinese martial arts. In 1936, at the 11th Olympic Games in Berlin, a group of Chinese martial artists demonstrated their art to an international audience for the first time. Eventually, those events lead to the popular view of martial arts as a sport.

Chinese martial arts experienced rapid international dissemination with the end of the Chinese Civil War and the founding of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949. Many well known martial artists chose to escape from the PRC's rule and migrate to Taiwan, Hong Kong,[27] and other parts of the world. Those masters started to teach within the overseas Chinese communities but eventually they expanded their teachings to include people from other ethnic groups.

Within China, the practice of traditional martial arts was discouraged during the turbulent years of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1969–1976).[3] Like many other aspects of traditional Chinese life, martial arts were subjected to a radical transformation by the People's Republic of China in order to align them with Maoist revolutionary doctrine.[3] The PRC promoted the committee-regulated sport of Wushu as a replacement to independent schools of martial arts. This new competition sport was disassociated from what was seen as the potentially subversive self-defense aspects and family lineages of Chinese martial arts.[3] Rhetorically, they also encouraged the use of the term Kuoshu (or Guoshu meaning "the arts of the nation"), rather than the colloquial term gongfu, in an effort to more closely associate Chinese martial arts with national pride rather than individual accomplishment.[3] In 1958, the government established the All-China Wushu Association as an umbrella organization to regulate martial arts training. The Chinese State Commission for Physical Culture and Sports took the lead in creating standardized forms for most of the major arts. During this period, a national Wushu system that included standard forms, teaching curriculum, and instructor grading was established. Wushu was introduced at both the high school and university level. The suppression of traditional teaching was relaxed during the Era of Reconstruction (1976–1989), as Communist ideology became more accommodating to alternative viewpoints.[28] In 1979, the State Commission for Physical Culture and Sports created a special task force to reevaluate the teaching and practice of Wushu. In 1986, the Chinese National Research Institute of Wushu was established as the central authority for the research and administration of Wushu activities in the People's Republic of China.[29] Changing government policies and attitudes towards sports in general lead to the closing of the State Sports Commission (the central sports authority) in 1998. This closure is viewed as an attempt to partially de-politicize organized sports and move Chinese sport policies towards a more market-driven approach.[30] As a result of these changing sociological factors within China, both traditional styles and modern Wushu approaches are being promoted by the Chinese government.[31] Chinese martial arts are now an integral element of Chinese culture.[32]

Styles

Main article: Styles of Chinese martial arts

See also: List of Chinese martial arts

The Yang style of Taijiquan being practiced on the Bund in Shanghai

China has a long history of martial traditions that includes hundreds of different styles. Over the past two thousand years many distinctive styles have been developed, each with its own set of techniques and ideas.[33] There are also common themes to the different styles, which are often classified by "families" (家, jiā), "sects" (派, pai) or "schools" (門, men). There are styles that mimic movements from animals and others that gather inspiration from various Chinese philosophies, myths and legends. Some styles put most of their focus into the harnessing of qi, while others concentrate on competition.

Chinese martial arts can be split into various categories to differentiate them: For example, external (外家拳) and internal (内家拳).[34] Chinese martial arts can also be categorized by location, as in northern (北拳) and southern (南拳) as well, referring to what part of China the styles originated from, separated by the Yangtze River (Chang Jiang); Chinese martial arts may even be classified according to their province or city.[22] The main perceived difference between northern and southern styles is that the northern styles tend to emphasize fast and powerful kicks, high jumps and generally fluid and rapid movement, while the southern styles focus more on strong arm and hand techniques, and stable, immovable stances and fast footwork. Examples of the northern styles include changquan and xingyiquan. Examples of the southern styles include Bak Mei, Choy Li Fut and Wing Chun. Chinese martial arts can also be divided according to religion, imitative-styles (象形拳), and family styles such as Hung Gar (洪家). There are distinctive differences in the training between different groups of the Chinese martial arts regardless of the type of classification. However, few experienced martial artists make a clear distinction between internal and external styles, or subscribe to the idea of northern systems being predominantly kick-based and southern systems relying more heavily on upper-body techniques. Most styles contain both hard and soft elements, regardless of their internal nomenclature. Analyzing the difference in accordance with yin and yang principles, philosophers would assert that the absence of either one would render the practitioner's skills unbalanced or deficient, as yin and yang alone are each only half of a whole. If such differences did once exist, they have since been blurred.

Training

Chinese martial arts training consists of the following components: basics, forms, applications and weapons; different styles place varying emphasis on each component.[35] In addition, philosophy, ethics and even medical practice[36] are highly regarded by most Chinese martial arts. A complete training system should also provide insight into Chinese attitudes and culture.[37]

Basics

The Basics (基本功) are a vital part of any martial training, as a student cannot progress to the more advanced stages without them; Basics are usually made up of rudimentary techniques, conditioning exercises, including stances. Basic training may involve simple movements that are performed repeatedly; other examples of basic training are stretching, meditation, striking, throwing, or jumping. Without strong and flexible muscles, management of Qi or breath, and proper body mechanics, it is impossible for a student to progress in the Chinese martial arts.[38][39] A common saying concerning basic training in Chinese martial arts is as follows:[40]

内外相合,外重手眼身法步,内修心神意氣力。

Which can be translated as:

Train both Internal and External.

External training includes the hands, the eyes, the body and stances. Internal training includes the heart, the spirit, the mind, breathing and strength.

Stances

Stances (steps or 步法) are structural postures employed in Chinese martial arts training.[41][42] They represent the foundation and exaggerated form of a fighter's base. Each style has different names and variations for each stance. Stances may be differentiated by foot position, weight distribution, body alignment, etc. Stance training can be practiced statically, the goal of which is to maintain the structure of the stance through a set time period, or dynamically, in which case a series of movements is performed repeatedly. The horse-riding stance (骑马步/马步 qí mǎ bù/mǎ bù) and the bow stance are examples of stances found in many styles of Chinese martial arts.

Meditation

In many Chinese martial arts, meditation is considered to be an important component of basic training. Meditation can be used to develop focus, mental clarity and can act as a basis for qigong training.[43][44]

Use of qi

Main article: Qigong

The concept of qì or ch'i (氣/气) is encountered in a number of Chinese martial arts. Qi is variously defined as an inner energy or "life force" that is said to animate living beings; as a term for proper skeletal alignment and efficient use of musculature (sometimes also known as fa jin or jin); or as a shorthand for concepts that the martial arts student might not yet be ready to understand in full. These meanings are not necessarily mutually exclusive.[note 1]

One's qi can be improved and strengthened through the regular practice of various physical and mental exercises known as qigong. Though qigong is not a martial art itself, it is often incorporated in Chinese martial arts and, thus, practiced as an integral part to strengthen one's internal abilities.

There are many ideas regarding the control of one's qi energy to such an extent that it can be used for healing oneself or others: the goal of medical qigong. Some styles believe in focusing qi into a single point when attacking and aim at specific areas of the human body. Such techniques are known as dim mak and have principles that are similar to acupressure.[45]

Weapons training

Most Chinese styles also make use of training in the broad arsenal of Chinese weapons for conditioning the body as well as coordination and strategy drills.[46] Weapons training (qìxiè 器械) are generally carried out after the student is proficient in the basics, forms and applications training. The basic theory for weapons training is to consider the weapon as an extension of the body. It has the same requirements for footwork and body coordination as the basics.[47] The process of weapon training proceeds with forms, forms with partners and then applications. Most systems have training methods for each of the Eighteen Arms of Wushu (s