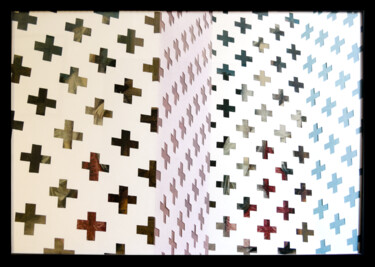

Sumit Mehndiratta, Optical construction, 2021. Sculpture, Wood / Digital Painting / Collage on wood, 114.3 x 114.3 x 10.9 cm.

Sumit Mehndiratta, Optical construction, 2021. Sculpture, Wood / Digital Painting / Collage on wood, 114.3 x 114.3 x 10.9 cm.

Kinetic Art, or Programmed Art, was born after World War II in conjunction with the decline of geometric abstraction. It is an artistic movement whose purpose is to illustrate the study of the mechanisms of vision, aspiring to a pictorial and plastic rendering of dynamism, optical phenomena and light. Just like abstractionism, the language employed by programmed art is aniconic, that is to say, without images, even though it differs from abstract movement in that it goes beyond any compositional ambition. In fact, the intent of the kinetic current is to overcome the traditional conception of art as a pure form of expression, aiming at involving the viewer on a purely perceptual and psychological level, rather than formal or emotional.

Valka Parusheva, Untitled 1, 2021. Collage on wood, 70x70 cm.

Valka Parusheva, Untitled 1, 2021. Collage on wood, 70x70 cm.

David Barnes, Marie Antoinette, 2019. Collage on wooden fabric, 75 x 107 cm.

David Barnes, Marie Antoinette, 2019. Collage on wooden fabric, 75 x 107 cm.

But what were the historical precedents of this art form?

Certainly, the origins of Programmed Art can be traced back to the experiences of Futurism, Dadaism, Constructivism, Concretism and Bauhaus, movements, trends and schools, whose instances were updated and renewed by kinetic artists, who experimented with a new way of relating art and technology. The most important precursors of this last current were: Marcel Duchamp, Naum Gabo, Antoine Pevsner, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Bruno Munari. In fact, date back to the period between 1913 and 1920 the most innovative experiments of Duchamp, among which stands out, in the context of programmed art, the iconic Bicycle Wheel (1913).

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1913. Metal wheel, wood, paint, 129.5 × 63.5 × 41.9 cm. New York: Museum of Modern Art. @_emme_dg

As for Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner, they spoke of Kinetic Art as early as 1920, when they mentioned its peculiarities in their Realist Manifesto. Ten years later, and more precisely in 1930, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy defined as kinetic the mechanism that made his Light-Space-Modulator, one of the first electrically powered sculptures, move. Finally, of extreme importance were the Useless machines created, in the 1930s, by Bruno Munari, devices to be hung from the ceiling which, composed of very light materials, were free to move in space. In addition, the Italian master was also responsible for the creation of the Manifesto del macchinismo (1952), in which the artist invited his colleagues to abandon the traditional methods of art, in order to begin to produce masterpieces using only machines.

Stacy Boreal, Silver spheres, 2021. Aluminum / acrylic on MDF panel, 100 x 70 cm.

Stacy Boreal, Silver spheres, 2021. Aluminum / acrylic on MDF panel, 100 x 70 cm.

Kinetic Art

In spite of these illustrious precedents, to speak of Programmed Art as a true avant-garde movement, one had to wait until 1955, the year in which, at the prestigious Denise Rene Gallery in Paris, the exhibition Le Mouvemente was held. The central theme of this exhibition was movement, well exemplified by the works of famous artists such as Alexander Calder, Marcel Duchamp, Jesus Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely and Victor Vasarely. This epochal exhibition highlighted the contrasting peculiarities of the nascent movement, which, while on the one hand promoted research into optical illusion effects, on the other, also focused on pure movement, determined both naturally and mechanically.

Alexander Calder, Double Gong, 1953. San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. @sagewoodmodernismweek

Yaacov Agam, Elysée hall, 1974. Paris: Pompidou Center . @janinesarbu

It was only in 1960, and more precisely in the city of Zurich, that this new form of art was indicated in the meaning with which we understand it today, or using the expression: Kinetic Art. This name was created on the occasion of the exhibition Kinetische Kunst, held at the Kunstgewerbemuseum, where the famous Enzo Mari exhibited, among others. It is important to note that during the 1960s, in addition to being recognized as a true movement, Programmed Art evolved, presenting multiple variants, including Lumino Kinetic art and Optical Art. During this same period, the popularity of kinetic art grew rapidly and strongly, through the organization of multiple exhibitions, culminating in the iconic 1965 event, held at Moma (New York) and entitled Beyond Informal. Finally, the golden age of programmed art, the 1960s and 1970s, lives on in the work of many popular contemporary artists, such as Bridget Riley, Rebecca Horn and Yaacov Agam.

Ferruccio Gard, Mostra abstract chromatism, 2018. Acrylic on canvas, 80 x 80 cm.

Ferruccio Gard, Mostra abstract chromatism, 2018. Acrylic on canvas, 80 x 80 cm.

Gianfranco Meggiato, Sun Sphere, 2020. Sculpture, bronze on metal, 23 x 20 x 20 cm / 5.00 kg.

Gianfranco Meggiato, Sun Sphere, 2020. Sculpture, bronze on metal, 23 x 20 x 20 cm / 5.00 kg.

Kinetic Art by the artists of Artmajeur

The optical, mechanical and spatial research of Kinetic Art continues, both in the work of the famous exponents of contemporary art, and in the parallel, innovative and experimental investigation carried out by the artists of Artmajeur. In fact, the works of the latter, including, for example, those of Gysin Broukwen, Jiri Genov and Seungwoo Kim, have definitely brought new life to this historic movement. On some occasions, however, it becomes evident how the research of the artists of Artmajeur also brings back reminiscences of the teachings of the great masters of the past, within a dialogue in which the connection between eras seems to never cease.

Gysin Broukwen, Kinetic face, 2019. Collages on paper, 100x70 cm.

Gysin Broukwen, Kinetic face, 2019. Collages on paper, 100x70 cm.

Gysin Broukwen: Kinetic face

Broukwen's digital print on paper, entitled Kinetic face, deals with the typical themes of the research of kinetic art in its variant of Optical art. This last movement, also known as OP-Art, was born around the sixties, with the aim of deepening the study of multidimensional illusion. In fact, Optical art aims to offer the viewer works rich in points of view, which convey, almost like revelatory visions, impressions of movement, of hidden or deformed images. This mode of artistic research also pursues the aim of stimulating and deeply involving the viewer, inducing him into a state of perceptive instability. With regard to the Kinetic face print, it is made up of small monochrome geometries that fit together and presents a variegated chromaticism, which gives different levels of depth to its many parts. In fact, in the central area of the work the optical illusion becomes much stronger, presenting itself as a deeper dimension within which the viewer can get lost or take refuge. Finally, the peculiarities and intentions of Broukwen's research can be seen as a continuation of the work of Victor Vasarely, founder and one of the main exponents of OP-Art, whose work is characterized by the use of geometric shapes, aimed at generating in the viewer strong illusions of three-dimensionality and movement.

Jiri Genov, Silent Advisor, 2020. Sculpture on metal, 2020. 71.5 x 21 x 39 cm / 18.50 kg.

Jiri Genov, Silent Advisor, 2020. Sculpture on metal, 2020. 71.5 x 21 x 39 cm / 18.50 kg.

Jiri Genov: Silent Advisor

Silent Advisor, a sculpture created by Jiri Genov, strongly re-proposes the simplicity of movement investigated by the artistic tendencies that preceded kinetic art, in particular, by Dadaism, since it has affinities with Duchamp's masterpiece: Bicycle Wheel. Indeed, in this 1913 ready-made, a bicycle wheel installed upside down, and supported by a fork, is free to perform its rotational movement. Similarly, Genov's sculpture, reporting another simple mechanism, moves by sympathetically rocking its head, as if to issue a benevolent nod of consent. In fact, referring to the author's own words, the sculpture was designed with this purpouse: the viewer should ask the work any question and, subsequently, push the button that activates its assertive movement. Therefore, this humorous sculpture, dated 2020, may have probably been inspired by the lock-down when, in the prevailing loneliness, a metal interlocutor would have been invaluable.

Seungwoo Kim, Circle XXXV, 2021. Sculpture, plastic / plaster / resin on metal, 16 x 30 x 16 cm / 10.00 kg.

Seungwoo Kim, Circle XXXV, 2021. Sculpture, plastic / plaster / resin on metal, 16 x 30 x 16 cm / 10.00 kg.

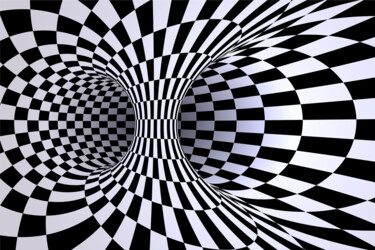

Seungwoo Kim: Circle XXXV

Seungwoo Kim's kinetic sculpture, made from two buttons, recalls the iconic painting Blaze 1 (1962), by Bridget Louise Riley, a British painter and one of the main exponents of the OP-Art movement, in terms of chromatism and repetition of the circular shape. The black and white zigzag lines of this latest masterpiece create the illusion of a vortex, which creeps into the center of the image, instilling in the human brain the vision of a swirl of concentric rings. In fact, the painting seems to move back and forth, suggesting an inward rotational motion. Although the work was done in black and white, as the eye tries to focus on the swirl in motion, additional prismatic colors are also visible. As for the work of the artist from Artmajeur, it turns out to be a very personal interpretation of the optical concepts expressed in Blaze 1, since, in this case, the visual illusion arises from the multiplicity of the buttons, which overlap, creating a dynamic spherical shape. Finally, it is the materials of Kim's artistic research that bring us back to the real world, after having lost ourselves in the complex mechanisms of vision.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli