Briefly introduce Laylat al-Qadr

Laylat al-Qadr, known as the Night of Power or Destiny, holds immense significance in Islam. It commemorates the night when the first verses of the Quran were revealed to the Prophet Muhammad by the angel Jibreel (Gabriel), marking the beginning of the divine communication that would continue to shape the Islamic faith. Muslims believe Laylat al-Qadr falls within the last ten nights of Ramadan, with particular emphasis on the odd nights. This night is described in the Quran as "better than a thousand months," highlighting its profound spiritual importance. It is a time when Muslims engage in prayer, recitation of the Quran, and reflection, seeking forgiveness, mercy, and blessings from Allah. The exact date of Laylat al-Qadr is not specified, encouraging Muslims to increase their worship throughout the final days of Ramadan in hopes of witnessing this blessed night.

Laylat al-Qadr across different Islamic communities

In the Middle East, the night is celebrated with communal prayers in mosques adorned with lights, scholarly lectures, Quranic recitations, and family gatherings for special meals. South Asia sees Laylat al-Qadr as a time of vibrant faith expression, with homes and mosques lit with lamps and candles, extended Taraweeh prayers, and acts of charity emphasizing forgiveness and mercy. Southeast Asia adds cultural festivities to the spiritual observance, including processions and storytelling about the Prophet Muhammad, fostering a connection to faith and history.

In Western countries, the night offers a chance for interfaith dialogue and community service, with mosques welcoming non-Muslims to share in the observance and Muslims engaging in acts of kindness. Regardless of the region, Laylat al-Qadr acts as a unifying force in Islam, promoting spiritual growth, self-reflection, and a recommitment to the teachings of the faith. The cultural and spiritual celebrations of this night highlight the diverse yet united devotion of the Islamic world, all seeking divine favor and guidance.

Historical Context and Significance

The celebration of Laylat al-Qadr, a key event in Islam commemorating the Quran's revelation, incorporates not just rituals and prayers but also artistic expression. This includes the revered art of calligraphy, displaying Quranic verses to inspire reflection; architectural design in mosques that fosters spiritual worship and community gathering; and the art of illumination, which beautifies manuscripts and spaces with light and color, symbolizing divine guidance. These artistic elements transform the night into a profound spiritual experience, blending worship with a celebration of faith's beauty. Thus, art on Laylat al-Qadr is not only for enjoyment but serves as a deep engagement with the sacred, highlighting the night's significance and enhancing the observance of this spiritually significant occasion.

Artistic Expressions Across Cultures

Laylat al-Qadr, the Night of Power, is a revered event in Islam, celebrated with artistic expressions worldwide, reflecting the cultural diversity of the Muslim community. In the Middle East, illuminated Quran manuscripts, adorned with intricate designs and calligraphy, stand out, especially those highlighting the Surah Al-Qadr. South Asian traditions enrich the night with textile arts and miniature paintings that depict the life of Prophet Muhammad and the night's significance. African Islamic art contributes through zellige tilework and community art projects, enhancing public spaces and fostering unity. In Southeast Asia, batik and wood carving decorate mosques and community centers, narrating the story of Laylat al-Qadr through Islamic calligraphy and motifs. These diverse artistic expressions across the Islamic world not only commemorate Laylat al-Qadr but also celebrate the rich cultural heritage of the Muslim community, illustrating the deep connection between faith and art.

The Significance of Calligraphy

Calligraphy, the art of beautiful writing, holds a place of unparalleled importance in Islamic art, serving as a bridge between the divine and the human. This art form is deeply rooted in the Islamic tradition, stemming from the desire to embody the beauty and perfection of the Quran's words in visual form. Especially in the context of Laylat al-Qadr, calligraphy transcends its aesthetic value, becoming a means to honor and commemorate the night of the Quran’s revelation to Prophet Muhammad. It is on this Night of Power that the profound connection between the written word and divine message is most vividly celebrated.

The significance of calligraphy during Laylat al-Qadr is multifaceted. It represents an act of devotion, a visual form of worship, wherein the act of creating calligraphy is imbued with meditation and reflection on the Quran's messages. Calligraphers, through their skill and spiritual intent, strive to capture the essence of Laylat al-Qadr, making the sacred text accessible and impactful. The visual representation of Quranic verses related to this holy night through calligraphy serves not only as decoration but as a focal point for contemplation and inspiration, guiding the faithful in their prayers and reflections.

One prominent example of calligraphic art associated with Laylat al-Qadr is the calligraphic depiction of Surah Al-Qadr (97th chapter of the Quran), which explicitly mentions the night. This Surah is often beautifully rendered in various styles, such as Thuluth, Naskh, or Diwani, and is displayed in mosques and homes. The elegance and complexity of the script underscore the Surah's significance, creating a visual reminder of the night's power and mercy.

Another example is the calligraphic panels featuring the names of Allah, Muhammad, or phrases like "Allahu Akbar" (God is the Greatest) and "Subhanallah" (Glory be to Allah), which are created specifically for the occasion. These artworks are not only admired for their beauty but are also used to adorn mosques and prayer spaces, enhancing the spiritual atmosphere of Laylat al-Qadr.

Illuminated calligraphy, where verses from the Quran are adorned with gold leaf, vibrant colors, and intricate borders, is another form of calligraphic art associated with this night. Such pieces are highly valued and often become the centerpiece of religious and cultural exhibitions during Ramadan, particularly in anticipation of Laylat al-Qadr. The use of illumination adds a divine glow to the calligraphy, symbolizing the light of guidance and revelation that the Quran brings into the world.

In creating these calligraphic artworks for Laylat al-Qadr, artists often incorporate symbolic elements such as the crescent moon, stars, or geometric patterns that represent the universe's order and the divine nature of creation. These elements, combined with the sacred text, offer a holistic visual experience that reflects the night's celestial and spiritual significance.

Through calligraphy, Muslims express their reverence for the Quran and Laylat al-Qadr, celebrating the night when the scripture was first revealed. This art form encapsulates the beauty of the divine word, serving as a bridge between the faithful and the profound messages of faith, guidance, and mercy contained within the Quran. As such, calligraphy not only adorns the physical spaces where Muslims gather to worship but also enriches their spiritual lives, highlighting the timeless connection between art, faith, and the divine.

Other Art Inspired by Laylat al-Qadr

Decorations

- Mosque Illuminations: Many mosques around the world are specially illuminated during the last ten days of Ramadan to commemorate Laylat al-Qadr. The use of lights and lanterns not only beautifies the mosques but also symbolizes the "Night of Power" as a moment of divine revelation and illumination.

- Home Decorations: Devotees often decorate their homes with lights, lanterns, and banners inscribed with calligraphy to mark the occasion. These decorations create a festive and reflective atmosphere, encouraging family and community gatherings for prayer and recitation of the Quran.

Artworks

- Miniature Paintings: Historically, Islamic miniature paintings have depicted scenes of the night skies on Laylat al-Qadr, symbolizing the descent of angels and the spirit of peace that pervades the night.

- Contemporary Art Installations: Some contemporary Muslim artists create installations and visual art pieces that interpret Laylat al-Qadr's themes, such as divine revelation, peace, and spirituality. These artworks often incorporate modern materials and techniques to engage with traditional themes in innovative ways.

Public Art and Community Projects

- Community Mural Projects: In some communities, artists and residents come together to create murals that celebrate Laylat al-Qadr's themes of peace, reflection, and community. These projects not only beautify public spaces but also foster a sense of communal solidarity and spiritual reflection.

These examples reflect the deep connection between faith and art in Islamic culture, illustrating how Laylat al-Qadr inspires a diverse range of artistic expressions across the globe.

Quran, Calligraphy, and Laylat al-Qadr

Folia from the manuscript consisting of purple paper, with a depiction of a tree on the right

Folia from the manuscript consisting of purple paper, with a depiction of a tree on the right

The Quranic manuscript from the Timurid period

The Quranic manuscript from the Timurid period, sometimes referred to as the Aqquyunlu Quran, is an exquisite piece of religious art from the 15th century, penned on Ming dynasty-produced paper. On June 25, 2020, this manuscript achieved a record-breaking sale at Christie's, fetching £7,016,250, which was over twelve times its pre-sale estimate, thus becoming the priciest Quranic manuscript ever auctioned at that point. Characterizing the manuscript are its 534 leaves, each measuring 22.6 by 15.5 cm, predominantly crafted from gold-speckled paper that was dyed and sourced from Ming China. The paper's blend with lead white grants it a texture comparable to soft silk. The manuscript showcases a spectrum of colors—ranging from pink and purple to cream, orange, blue, and turquoise—and includes pages that feature artistic renderings of natural scenery, plants, and birds. The Arabic text is beautifully inscribed in the naskh calligraphic style, while the titles of the surahs and the divisions of the thirty juz' (sections) are accentuated with the majestic thuluth script.

However, the auction of this manuscript was met with criticism from the academic community, who felt that the sale detracted from its intrinsic historical, cultural, and spiritual importance. Moreover, there were concerns regarding the manuscript's origins, with some critics pointing to Christie's lack of transparency about its history prior to the 1980s, suggesting that this could potentially mask historical instances of looting and illegal trade. The gold illumination, particularly the tree on the right, could symbolize the Tree of Life or the concept of divine creation and sustenance, both fitting themes for the contemplation of the Quran's revelation during Laylat al-Qadr. This night is about the descent of divine wisdom, and artworks like this folio serve to enhance the spiritual atmosphere, providing a visual meditation aid that complements the recitation and reflection on the Quran’s verses. While we cannot definitively link this specific manuscript to Laylat al-Qadr without historical records confirming its use for that purpose, its grandeur and the sacredness of its content align with the reverence of that night. Such a manuscript would be a fitting centerpiece for Laylat al-Qadr observances, where the Quran becomes the focal point of Muslim worship and devotion.

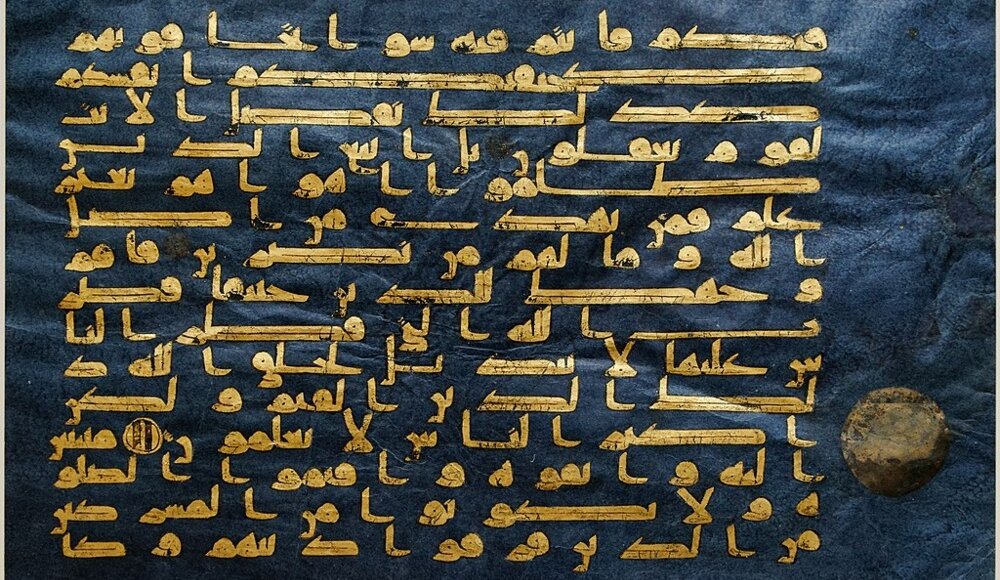

Folio in the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

Folio in the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

The Blue Quran

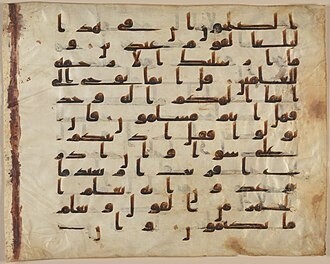

Detached folio. Surah Al-Anbiya Ayah 105-110 from the Samarkand Kufic Quran in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Detached folio. Surah Al-Anbiya Ayah 105-110 from the Samarkand Kufic Quran in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Samarkand Kufic Quran

The Samarkand Kufic Quran, also recognized as the Uthman Quran, Samarkand codex, Samarkand manuscript, and Tashkent Quran, is a manuscript of the Quran from the 8th or 9th century, penned in the Kufic script within what is now modern Iraq. This historic manuscript was later transported by Tamerlane to Samarkand, which is in today's Uzbekistan, and it currently resides in the Hast Imam library in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. This manuscript is reputed to have been in the possession of Uthman ibn Affan, the third caliph. Orthographic and palaeographic analyses suggest the manuscript likely originates from the 8th or 9th century. Radiocarbon dating indicates a 95.4% probability that the manuscript dates between 775 and 995 AD. Another folio, kept by the Religious Administration of Muslims in Tashkent, has been dated between 595 and 855 AD, with a 95% probability.

Tradition vs. Academic Analysis Traditionally, this Quranic copy is considered among those ordered by Uthman ibn Affan. Islamic tradition holds that in 651, 19 years following Prophet Muhammad's passing, Uthman convened a committee to compile a standardized Quran text. While Uthman dispatched five of these official copies to major Islamic cities of the time, retaining one for himself in Medina, it's unlikely the Samarkand Quran is one of these. The only other presumed surviving copy is in Turkey's Topkapı Palace, though further research suggests the Topkapı manuscript dates to a later period. After Uthman's reign, Ali, his successor, reportedly took the Uthmanic Quran to Kufa (present-day Iraq). Centuries later, Tamerlane captured this region and transported the manuscript as a trophy to Samarkand. Alternatively, it's said that Khoja Ahrar, a Sufi master from Turkestan, brought the Quran to Samarkand from the ruler of Rum as a gift after healing him. The manuscript remained in Samarkand's Khoja Ahrar Mosque for four centuries. Verified History In 1869, Russian General Abramov acquired the manuscript from the mosque's imams and presented it to Konstantin von Kaufmann, the Governor-General of Turkestan, who then forwarded it to the Imperial Library in Saint Petersburg (now the Russian National Library).

The manuscript garnered scholarly attention, leading to a facsimile edition published in 1905 by Orientalists, becoming a rarity. Russian Orientalist Shebunin provided the first comprehensive dating and description in 1891. Following the October Revolution, Lenin gifted the Quran to the Muslims of Ufa in Bashkortostan as a gesture of goodwill. Later, after requests from the Turkestan ASSR, the manuscript was relocated to Tashkent in 1924, where it has remained. The Samarkand manuscript is currently housed in the Telyashayakh Mosque's library in Tashkent's old "Hast-Imam" (Khazrati Imom) district, near the grave of the 10th-century scholar Kaffal Shashi. Additionally, a folio from the sura Al-Anbiya is part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection in New York City, USA. The manuscript, missing its beginning and ending, lacks vocalization in its text, reflecting the Arabic script's style of that era. When we consider its relation to Laylat al-Qadr, the Night of Decree or Power, this historical Quranic folio takes on added significance. Laylat al-Qadr is the night during which Muslims believe the first revelation of the Quran was sent down to the Prophet Muhammad, beginning the journey of its divine transmission. Manuscripts such as the Samarkand Kufic Quran embody the reverence with which the Quran has been regarded throughout Islamic history.

They are physical manifestations of the devotion to preserving and venerating the holy text, which is at the heart of Laylat al-Qadr's observance. On Laylat al-Qadr, Muslims engage in increased prayer and recitation of the Quran, seeking to gain the blessings and mercy that are believed to be particularly abundant on this night. A manuscript of such historical and spiritual value as the Samarkand Kufic Quran would thus serve as a potent symbol of the divine message's endurance and the unbroken chain of its transmission from the time of the Prophet to the present day. It connects worshippers with their ancestors in faith, acting as a tangible link to the night when the words it contains were first received.

Selena Mattei

Selena Mattei