Flemish art played a central role in the development of European painting between the 15th and 17th centuries, distinguishing itself through the innovative use of oil painting and an exceptional attention to detail. Among the most characteristic subjects of this artistic tradition are still lifes, interiors, and genre scenes, each with its own unique features and symbolic significance.

Flemish still lifes are renowned for their extraordinary ability to depict everyday objects with incredible realism and refined color compositions. These works, often enriched with symbolic elements, reflect the concept of vanitas, emphasizing the fleeting nature of life and the transience of material possessions. Skulls, extinguished candles, wilted flowers, and ripe fruits are some of the recurring motifs that evoke the ephemerality of existence. Painters such as Osias Beert elevated still life painting to extraordinary levels of mastery.

Flemish interior representations, on the other hand, are characterized by the meticulous depiction of domestic spaces, which become the stage for bourgeois life. These works offer a window into the society of the time, highlighting the home as a space of order and well-being. A notable example is the work of Jan Jozef Horemans the Younger, known for his depictions of bourgeois interiors and portrayals of merchants and shopkeepers.

Flemish genre scenes illustrate moments of everyday life, from popular celebrations to markets, taverns, and domestic activities. These paintings are not mere representations of common tasks but often convey moral and social messages. David Teniers the Younger was one of the most celebrated Flemish painters of the 17th century, renowned for his skill in capturing daily life, idyllic landscapes, and genre scenes with unparalleled mastery.

It is therefore interesting to highlight how the influence of the iconic subjects of Flemish art extends to the present day, inspiring contemporary artists on ArtMajeur who reinterpret these traditional genres with new visual languages.

"Harvest" (2008) Painting by Tatiana Mcwethy

"Harvest" (2008) Painting by Tatiana Mcwethy

Juicy fruits (2023) Painting by Yana Rikusha

Juicy fruits (2023) Painting by Yana Rikusha

The Legacy of Flemish Art in Still Lifes

The paintings of Tatiana McWethy and Yana Rikusha demonstrate how the Flemish tradition continues to live on and inspire contemporary art. Despite their modern sensibilities, both artists draw from the techniques and themes of the old masters, keeping alive the legacy of a golden age in European painting. Their attention to detail, masterful use of light, and pursuit of compositional harmony connect these works to the great tradition of Flemish painting, proving that the beauty of still life is timeless and ever relevant.

In Harvest by Tatiana McWethy, we can observe the use of strong chiaroscuro, typical of Flemish painting, which enhances the volume of objects and creates a sense of dramatic depth. The arrangement of items on the table—where the fruit almost seems to spill over toward the viewer—recalls the baroque compositions of Frans Snyders and Jan Fyt. Additionally, the inclusion of a richly decorated tablecloth and reflective materials, such as the metallic bowl, evokes the meticulous attention to detail that characterized Flemish masters.

Similarly, Juicy Fruits by Yana Rikusha embraces this tradition through a more minimalistic and modern composition, yet one that remains equally powerful. The artist employs a delicate color palette and soft lighting to create an intimate and refined atmosphere. The reference to Flemish artists is evident in the hyper-realistic rendering of surfaces—from the texture of pomegranate peels to the transparency of a glass of water. The choice to include an architectural element in the background, such as the decorative tile hanging on the wall, echoes the detailed interiors of artists like Willem Kalf, creating a sense of orderly and harmonious domestic space.

Le Désert Bleu (2022) Painting by Manuel Dampeyroux

Le Désert Bleu (2022) Painting by Manuel Dampeyroux

Empty Room # 64 (2008) Photography by Marta Lesniakowska

Empty Room # 64 (2008) Photography by Marta Lesniakowska

The Flemish Interior and the Contemporary Interior

The works of Manuel Dampeyroux and Marta Lesniakowska demonstrate how the legacy of Flemish art continues to thrive in contemporary art: the attention to light, the rigorous perspective construction, and the evocative use of interiors connect these artists to the masters of the past. However, while the traditional Flemish interior was often animated by human figures interacting with the space, modern interpretations sometimes omit the human presence, replacing it with a more abstract and metaphysical reflection. This shift highlights how the concept of the interior is not merely a physical representation of a place but also a mental and emotional dimension, capable of engaging with time and memory.

Le Désert Bleu by Manuel Dampeyroux carries forward this legacy, which was never limited to depicting physical spaces but rather transformed interiors into psychological landscapes, where the arrangement of objects and the interplay of light contributed to a sense of balance and order. The ArtMajeur painter follows this tradition through a rigorously staged composition: the room, dominated by an "essential" color palette and deep blue tones, recalls Flemish interiors, where natural light filtering through a side window creates a suspended, contemplative atmosphere.

The artist employs the concept of pictorial silence to instill in the scene a feeling of suspended time, a characteristic also found in Flemish paintings, where figures seem frozen in action. Additionally, the use of reflective elements, such as the fireplace positioned at the center of the composition, echoes the carefully studied perspective of the old masters, who often placed fireplaces or windows as visual vanishing points to organize space and guide the viewer's gaze.

However, what distinguishes this contemporary reinterpretation from the traditional Flemish interior is the way the human figure is treated. Unlike Flemish works, where people were immersed in everyday gestures, in Le Désert Bleu, the two women present in the scene appear more like symbolic projections than narrative subjects. Identical in clothing and posture, they sit on opposite sides of the composition in a static and absorbed attitude, their eyes closed, as if suspended between reality and inner contemplation.

Another central aspect of the quintessential Flemish interior is the role of light in defining space and creating a sense of three-dimensionality. Marta Lesniakowska’s photograph Empty Room #64 adopts this approach through an in-depth analysis of the relationship between brightness and architectural structure. The large central window, through which a diffuse, glacial glow enters, recalls the same openings that illuminated the rooms in the works of Jan Jozef Horemans the Younger, where natural light gently sculpted the volumes of objects and furniture.

However, unlike Flemish interiors, where the human presence was almost indispensable to narrate daily life, Lesniakowska’s photograph completely abandons the human figure, transforming the scene into a reflection on memory and absence. The use of red sofas and the contrast with the cold, time-worn walls echo the chromatic interplay typical of Flemish masters, who often incorporated warm-colored fabrics and furnishings to break the monotony of enclosed spaces.

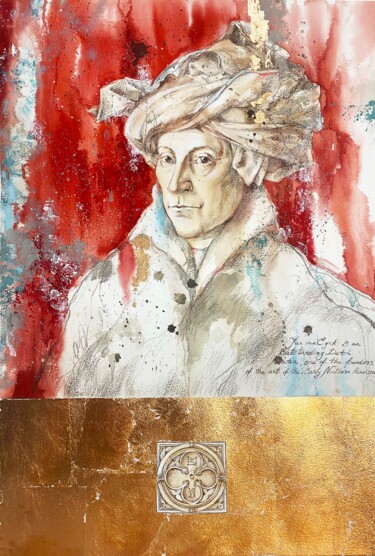

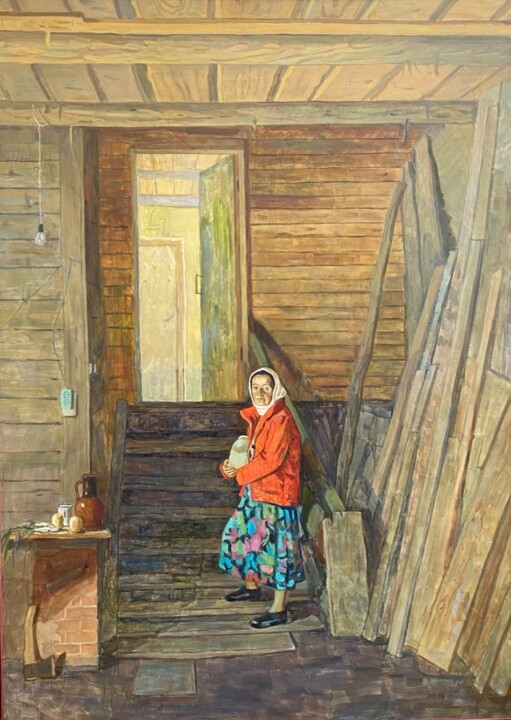

Woman with the milk jar (2023) Painting by Anastasiia Goreva

Woman with the milk jar (2023) Painting by Anastasiia Goreva

Neighborhood Nights (2024) Painting by Trayko Popov

Neighborhood Nights (2024) Painting by Trayko Popov

Genre Scenes Yesterday and Today

Although belonging to different artistic contexts and sensibilities, both of the works above share the intent of capturing fragments of everyday life—an objective also pursued by the often-cited Flemish art. Goreva, with her solemn depiction of a peasant woman, evokes the quiet strength of the everyday portraits created by the masters of the genre, while Popov explores the social and collective dimension of the genre scene, turning the viewer into a silent witness of urban life.

Starting with Anastasiia Goreva’s painting Женщина с банкой молока (Woman with a Jar of Milk), the work fits perfectly within this tradition due to its meticulous attention to detail and the construction of an environment rich in meaning. The artist does not simply depict a female figure but transforms her into an archetype, an icon of strength and resilience. Dressed in a striking red that makes her the visual focal point of the composition, the woman stands against a simple and austere domestic setting, composed entirely of wooden elements. Her gaze directed at the viewer and the firm placement of her hands around the jar of milk suggest a moment of pause and contemplation, as if she has been caught in a suspended instant of her daily routine.

While Goreva explores the domestic and intimate dimension of the genre scene, Trayko Popov, in Neighborhood Nights, expands the visual field and brings the narrative into the public sphere, depicting social life through the windows of an urban neighborhood.

The scene is constructed with a vibrant and contrasting color palette: the deep blue of the night sky contrasts with the warm glow of the interior lights, creating a sense of intimacy and community. Each window tells its own story, inhabited by figures who converse, dine, relax, or immerse themselves in moments of solitude.

It becomes evident that, compared to the Flemish tradition, Neighborhood Nights moves away from classical realism. The artist opts for a more pronounced stylization and an almost expressionist use of color, reducing hyperrealistic details in favor of greater visual and emotional immediacy. This stylistic shift does not represent a break with tradition but rather an evolution and expansion of the everyday perspective made famous by the Flemish masters.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli