Portrait by Daniele da Volterra, c. 1545

Portrait by Daniele da Volterra, c. 1545

Who was Michelangelo?

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, commonly known as Michelangelo, was an Italian artist who lived during the High Renaissance. He was born in the Republic of Florence on March 6, 1475, and passed away on February 18, 1564. Michelangelo was a sculptor, painter, architect, and poet, and his work was greatly influenced by classical antiquity. He had a significant impact on Western art and is considered an exemplary Renaissance man, much like his contemporary Leonardo da Vinci. Michelangelo is well-documented due to the large amount of surviving correspondence, sketches, and reminiscences. He was praised by his contemporaries as the most accomplished artist of his time.

Michelangelo gained fame at a young age with two of his most famous sculptures, the Pietà and David, which he created before turning thirty. Although he didn't consider himself a painter, his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, particularly the scenes from Genesis on the ceiling and The Last Judgment on the altar wall, are regarded as highly influential in Western art history. He also played a key role in the development of Mannerist architecture with his design of the Laurentian Library. Later in life, at the age of 71, Michelangelo became the architect of St. Peter's Basilica, succeeding Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. He completed the western end of the basilica and designed the dome, which was modified after his death.

Michelangelo was the first Western artist to have his biography published while he was still alive. Three biographies were published during his lifetime, with Giorgio Vasari's biography praising him as surpassing any artist, past or present, in all three artistic disciplines. During his lifetime, Michelangelo was often referred to as Il Divino, meaning "the divine one." His contemporaries admired his ability to evoke awe in viewers with his art, a quality known as terribilità. Other artists attempted to imitate his expressive style, leading to the emergence of Mannerism, a short-lived movement following the High Renaissance.

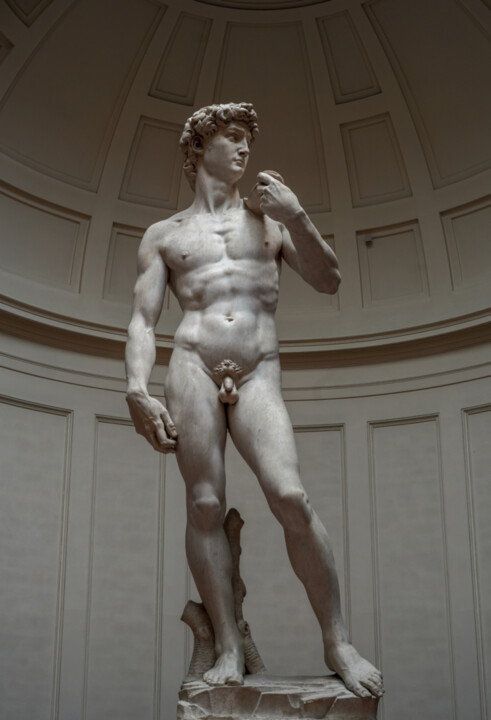

Michelangelo, David, c. 1501-1504. Marble sculpture, 517 cm × 199 cm. Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, Italy.

Michelangelo, David, c. 1501-1504. Marble sculpture, 517 cm × 199 cm. Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, Italy.

Michelangelo and the Renaissance Era

During the Renaissance, Michelangelo was highly sought after for lucrative commissions, which led to his extensive work in the Sistine Chapel. The project involved intricate decoration of the chapel's ceiling and was completed in the 16th century. Among the various sections of the vast fresco, the Creation of Adam stands out as one of the most significant and artistically impressive parts. This painting depicts a renowned religious moment from Christian teachings, which holds great importance in Italy, a country deeply rooted in Christianity. The scene captures God breathing life into Adam, who would become the first man, and later joined by Eve, marking the beginning of the human race. The theme of Adam and Eve has been a popular subject in countless paintings, particularly during the Renaissance period when religion wielded significant influence in society.

The iconic depiction of the connection between Adam's and God's fingers, symbolizing the creation of life, has garnered its own fame. Many people prefer this cropped version of the larger work and acquire it as an art print, poster, or stretched canvas to adorn their homes. The panel featuring the Creation of Adam was one of the final additions to the Sistine Chapel's ceiling, which has attracted countless visitors over the past 500 years. Regular maintenance work is conducted to preserve this extraordinary fresco and prevent any damage.

The enduring legacy of the Creation of Adam has inspired and captivated countless individuals, earning respect and admiration from both art scholars and the general public.

Michelangelo created four panels within the Sistine Chapel, depicting episodes from the book of Genesis, which are still well-known among the substantial Christian population in Europe and many other continents. Italian art, in general, played a leading role in spearheading the Renaissance movement in Europe, influencing contemporary artistic developments that we appreciate today. The Creation of Adam has become an iconic image recognized by almost everyone, regardless of their knowledge of the artist or the painting's intended meaning.

This renowned artwork can easily be considered as famous as other significant works, such as Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa. Michelangelo, like his contemporary da Vinci, showcased an impressive range of skills, as demonstrated in his creation of the David sculpture. Today, Creation of Adam prints are regularly purchased worldwide, reflecting the enduring popularity of Italian art from the 15th and 16th centuries. Italian art played a pivotal role in introducing new ideas and techniques to European art, breathing new life into an artistic landscape that had become relatively stagnant during the Middle Ages.

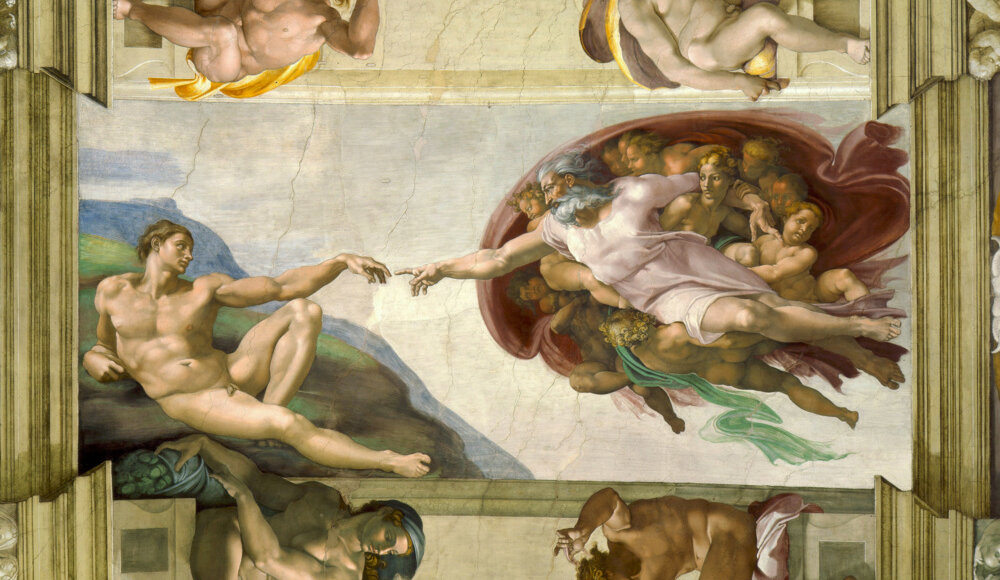

Michelangelo Buonaorroti, The Creation of Adam, 1508-12. Fresco, 280×570 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo Buonaorroti, The Creation of Adam, 1508-12. Fresco, 280×570 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

The Creation of Adam (c. 1511)

On the right side, there is a depiction of God, suspended in the air, surrounded by a halo supported by angels and cherubim. On the left side, we see Adam lying down on a meadow, overlooking a grassy slope. Adam, the first human, is in a semi-reclined position, completely naked, with his arm resting on his right knee. His right arm is resting on the ground, propping up his torso. He appears youthful, with strong and muscular features. His right leg is stretched out along the slope, while his left leg is bent. Adam is portrayed in profile, and it seems as though he is coming to life as he looks towards God and raises his left arm in His direction.

God is adorned in a rose-colored robe, and He is depicted stretched out towards the left, supported by angels. His long beard and gray hair are gently moved by the wind. The angels and God are surrounded by a wide, kidney-shaped purple veil. Below them, a thin, transparent green fabric hangs and flutters under the angel who supports God. The encounter between God and Adam takes place against a background that lacks specific details.

In the scene, we catch a glimpse of the hand of a young Ignudo beneath Adam's body. The Ignudo refers to the male human figures positioned at the corners of the narrative panels.

In contrast to the previous depictions of God by other artists, Michelangelo's portrayal in this artwork is a bold departure. Traditionally, God has been depicted as a majestic and all-powerful ruler of humanity. One would expect such a divine figure to be painted wearing regal attire and exuding a sense of grandeur. However, Michelangelo takes a different approach by presenting God as a simple, elderly man clad in a light, unadorned tunic, with much of his body exposed. This representation raises an intriguing question: What if this humble, aged face is the true visage of God? It offers an intimate portrayal of His essence. God is depicted as approachable, tangible, and intimately connected to His creation, as His figure takes on a curved shape, reaching out towards Adam.

Color and texture

The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo is an example of a fresco painting, where the artist applied paint onto wet plaster. The color palette used in the painting appears light, consisting primarily of flesh tones such as various shades of brown and creamy colors. Additionally, there are touches of yellow for the hair of certain figures, while God's hair is depicted in a cooler grayish-blue color and Adam's hair appears as a darker brown with lighter highlights.

The artist skillfully employed darker areas of shading on the figures, effectively emphasizing their shapes and anatomy to create a sense of depth. While there are other colors present in the composition, they are not excessively vibrant. These include the greens representing the grass to the left and the scarf to the right, as well as the blue-gray hues representing either the rocky formation or the sky behind Adam. These cooler color schemes contrast with the deeper shade of red seen in the cloth behind God, which is a warmer color.

Overall, there is a harmonious use of color throughout the composition, primarily due to the similar skin tones employed. The backdrop features contrasting colors such as green, blue, and red, providing a different color value compared to the lighter tones used for the figures. The remaining background of the fresco is a neutral white-gray color, further highlighting the main figures of God and Adam in the foreground. This background could be interpreted as white clouds against the sky. The drapery and clothing have an implied texture, appearing light and translucent. Furthermore, the figures themselves are depicted with smooth skin textures, with some displaying plump flesh while others exhibit more muscular definition.

The flowing and soft appearance of the figures' hair is worth noting, particularly God's hair, which appears to billow to the right of the composition, seemingly influenced by an unseen wind or breeze.

Lines

The positioning of God and Adam in the composition creates a sense of balance. They are strategically placed to divide the artwork into two distinct parts. Adam's form is often described as "concave," while God's form is seen as "convex." This stark contrast between the two figures not only adds visual interest but also hints at a deeper meaning and the relationship between God and Adam.

Moreover, the backdrops behind each figure predominantly feature curved shapes, which stand in contrast to the strong horizontal line formed by the outstretched arms and joined hands of God and Adam. This horizontal line serves to connect the two previously mentioned parts of the composition.

East side of the Sistine Chapel, from the altar end.

East side of the Sistine Chapel, from the altar end.

Symbology

The background of the scene in Adam's Creation does not contain intricate details, symbolizing the birth of humanity. This minimalist backdrop allows the characters to stand out prominently against the light background, conveying a clear and iconic message. According to tradition, God is supported by angels and cherubim, who interestingly take on the appearance of human figures, specifically teenagers and children. These angelic beings are portrayed with substantial and realistic bodies, emphasizing their physical presence and effort in supporting God. Furthermore, their faces are highly distinctive, each bearing different expressions.

The depiction of Adam's Creation is the most renowned scene within the vault of the Sistine Chapel. Its fame is largely attributed to the iconic image of the two fingers coming close to touching. In this image, God the Father extends His arm towards Adam, positioned below, while Adam raises his own hand above. Both figures have their arms outstretched, with their index fingers depicted just moments away from making contact. Michelangelo aimed to immortalize the precise instant when the Creator is about to establish physical contact with His creation, infusing Adam with the spark of life. The potency of this image, which has become an emblem of creation, is also enhanced by the elegance of the gestures and postures of the two figures. Additionally, Adam's figure possesses a captivating visual strength due to the meticulous sculpting that accentuates the volumes of his nude body. Some historians note a similar gesture in Sandro Botticelli's Annunciation of Cestello, further emphasizing the significance of this gesture in art history.

Now let's turn our attention to the red backdrop behind the image of God. Some believe that this backdrop resembles a brain. This has led to the conclusion that God intentionally withheld intelligence from Adam, keeping him unaware of the knowledge of good and evil. It was only after Adam had sinned that God allowed him to possess this knowledge. However, if the analysis of this painting has taught us anything, it is that God's creation of man was not merely a matter of bringing him into existence; it was about forging a deep relationship with him. Upon closer examination of the painting, one can truly appreciate the boldness with which it was created. Michelangelo's brushstrokes are confident and energetic, leaving no room for chance. Numerous books have been written, and reinterpretations have been made, yet the true beauty of the Creation of Adam lies not in its status as a timeless masterpiece, but in its ability to resonate with every single person on this earth. It represents the beginning of all of us, regardless of our differences. This painting has been interpreted countless times, yet it still eludes complete understanding. There is something about beholding it that defies verbal expression, no matter how poetic. In those more than a hundred brushstrokes, Michelangelo painted life itself. He depicted the source of life, the commencement of life, and by including the image of the Christ child, he captured the concept of eternal life. He transports us to that moment before it all began, bringing us back to the genesis of humanity, when the human race was but a vague concept in the air. The incredible attention to detail in this piece is delightful, and its seamless integration with the other elements of the ceiling is awe-inspiring.

It is remarkable how many artists have attempted, yet failed, to truly capture the moment of Adam's creation. Michelangelo, however, successfully captures the entirety of the process, leaving nothing out. This fresco endures as one of the most remarkable artistic achievements. As Adam reclines on the earthly terrain, his physical strength is evident to any observer. He embodies the idealized figure of a Greek or Roman male, with his grace and rippling muscles. However, despite his physical perfection, this creation remains incomplete. Adam still reaches out to God, demonstrating his reliance on the Creator. God sustains him, and even though Adam appears whole, he extends himself to receive the simple touch of God. The image of God mirrors the image of Adam, and as they gaze into each other's eyes, an intense and beautiful connection is established between them. Adam looks at his creator with longing, and in this moment, Michelangelo captures the essence of what it means to be human. The painting portrays the threshold of creation as Adam stretches out to receive the nourishment necessary for his physical form to survive. Meanwhile, God reaches out to bestow upon His creation the spirit and the soul. By capturing this singular moment, the creation of Adam's physical and spiritual self is eternally etched in the memory of every generation.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Cumaean Sibyl, c. 1511. Fresco, 375×380 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Cumaean Sibyl, c. 1511. Fresco, 375×380 cm. Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Meaning

The primary interpretation of this painting revolves around the creation of humankind and the beginning of the human race. However, upon closer examination, the artwork delves into the profound relationship forged between the Creator and His creation. With a simple extension of His arms, God brings Adam into existence and directs his attention towards the Christ child, who serves as Adam's savior. In this portrayal, the Creator exhibits omniscience, foreseeing the fall of humanity after succumbing to temptation from the devil. Thus, God anticipates this downfall and offers a ready solution through Christ.

Nevertheless, there remains a significant ambiguity within the painting. Are Adam and God letting go of each other, or are they reaching out to one another? The depiction of their fingers makes it challenging to discern whether God and man are satisfying their shared desire to coexist, or if they are parting ways, with man embarking on an independent life. When observing Adam's posture, we notice a sense of relaxation. This can be interpreted to mean that although he is alive, he is still lacking something vital. Consequently, Adam reaches out to God, longing to receive the element that distinguishes him from other creatures roaming the earth. On the other hand, God's focused appearance suggests an active engagement, as if diligently working to perfect His creation. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the figures are reaching out to each other in a union rather than separating.

Interestingly, even geographers have interpreted this painting as depicting two landmasses joined by a narrow strip but separated by a vast canal. Likewise, scientists have analyzed the image as a symbol of the birth of humanity. They draw their hypothesis from the red backdrop, which they interpret as a representation of a human uterine mantle, while the green scarf symbolizes a recently severed umbilical cord.

All these interpretations, to some extent, converge on the same idea. However, the question remains: why did Michelangelo depict the hands in that particular way? Why not make them touch? Contemplating this detail can be frustrating. Yet, this single aspect is what has made the painting renowned. The small space between the two fingers, measuring just under an inch, compels viewers to take a second and third look at the entire picture. Despite the conclusions reached regarding the painting's meaning, it remains enigmatic. Upon closer inspection, one is inclined to perceive what is absent – to sense a force that seems to exist between the two fingers. It is akin to an electric charge, and as the image embeds itself in the mind, a realization emerges, making the observer aware of the painting's profound significance. This is the very beginning; one misstep, and humanity would have taken an entirely different path. Delicacy is involved, and by observing God's unwavering focus on the task at hand, one can sense His pursuit of nothing short of perfection.

It becomes even more intriguing when one envisions the two fingers making contact. Oh, the sensation Adam must have experienced as the touch of immortality permeated his very soul. Michelangelo captures what the church has endeavored to explain to its followers for centuries – the divine spark of life. He presents evidence that God and man are nothing if not the perfect reflection of one another. Through the Creation of Adam, Michelangelo silently encompasses the past, present, and future of humanity within a single frame. One could say that this image was crafted at the very dawn of time, for its depiction is truly incredible. To the untrained eye, it may appear as a mere representation of two figures reaching out to one another. Yet, upon closer examination, that fleeting moment before God's finger breathes life into Adam's finger becomes the essence of everything we comprehend and believe.

The painting exalts God in various ways. The mere fact that He initiates an entire race of people with a simple touch of a finger should be sufficient to establish His position as the Almighty. However, Michelangelo takes it a step further. God does not need to physically touch Adam for an observer to feel the power, strength, and life being transferred from one finger, across the gap, and into the other finger. It is this element that rightfully garners the painting's recognition. However, there is another perspective to consider. For those unfamiliar with Michelangelo or his work, and who have not encountered the painting's title or the story of creation, it may be challenging to comprehend the essence of the Creation of Adam. From such a standpoint, without knowledge of the spark between the fingers, the presence of the Christ child, or any association with the birth of mankind, the painting simply portrays two figures inclining towards each other.

The delicate connection between the creator and creation only becomes apparent once the viewer understands the subject matter of the painting. However, there is another aspect to consider. The notion of power portrayed in this artwork is not a result of the image itself. Most people are familiar with the story behind the painting, which can blind them to the fact that it simply depicts two figures delicately reaching out to one another, both filled with longing and restraint. Their fingers are stretched out, almost touching, but their hands extend into a void of emptiness. Moreover, the angels supporting the form of God appear to be struggling in their task. When divorced from the influence of the creation narrative, the painting transforms into a representation of love and friendship. It transcends being solely about God's Creation of Adam and instead conveys the universal desire for human connection. This aspect of the artwork evokes both comfort and heartbreak. It is difficult to imagine humanity without the presence of God, yet envisioning the relationship between these two figures as strictly one-sided is not entirely comforting either.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Delphic Sibyl, c. 1508-10. Fresco, 350×380 cm . Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Delphic Sibyl, c. 1508-10. Fresco, 350×380 cm . Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

Context of creation

In 1505, Michelangelo was summoned back to Rome by the newly elected Pope Julius II. The pope commissioned him to construct a grand tomb, which was intended to feature forty statues and be completed within five years.

However, due to various interruptions and competing demands placed on Michelangelo under the patronage of the pope, the tomb was never finished to the artist's satisfaction despite him dedicating 40 years to the project. The tomb, located in the Church of S. Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, is renowned for its central figure of Moses, completed in 1516. Two other statues originally destined for the tomb, known as the Rebellious Slave and the Dying Slave, are now housed in the Louvre Museum.

During this period, Michelangelo undertook the monumental task of painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, a project that spanned approximately four years from 1508 to 1512. According to the account of Michelangelo's biographer Condivi, Bramante, who was involved in the construction of St. Peter's Basilica, harbored resentment toward Michelangelo's commission and influenced the pope to assign him an unfamiliar medium in hopes that he would fail.

Originally tasked with painting the Twelve Apostles on the triangular pendentives supporting the ceiling, Michelangelo successfully convinced Pope Julius to grant him artistic freedom and propose a more ambitious and intricate scheme. The final composition depicted various scenes, including the Creation, the Fall of Man, the Promise of Salvation through prophets, and the genealogy of Christ. The artwork formed part of a larger decorative scheme within the chapel that conveyed key Catholic Church doctrines.

The vast composition covered an area of over 500 square meters and featured more than 300 figures. The central portion showcased nine episodes from the Book of Genesis, encompassing God's Creation of the Earth, the Creation of Humankind and their fall from grace, and the depiction of Noah and his family as representatives of humanity. Adorning the pendentives supporting the ceiling were twelve individuals who prophesied the coming of Jesus, including seven prophets of Israel and five Sibyls, prophetesses from the Classical world. Notable paintings on the ceiling included The Creation of Adam, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the Deluge, the Prophet Jeremiah, and the Cumaean Sibyl.

The Sistine Chapel as it may have appeared in the 15th century (19th-century drawing).

The Sistine Chapel as it may have appeared in the 15th century (19th-century drawing).

Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel

Despite his initial reluctance, Michelangelo Buonarroti accepted the commission in 1508 to paint nine scenes from Genesis on the vault of the Sistine Chapel, which also included figures of prophets, sibyls, and ancestors of Christ.

The project posed numerous challenges. The vast surface of the vault, combined with Michelangelo's refusal to enlist the help of assistants, made the task even more demanding. The curved shape of the vault presented optical distortion issues, and the height of the ceiling necessitated expensive scaffolding. Additionally, the pope was eager for the work to be completed promptly.

However, despite these obstacles, Michelangelo demonstrated his extraordinary genius and managed to complete the frescoes by 1511, finishing in less than four years.

Initially, Michelangelo began with the last scenes in the narrative order, featuring numerous small-sized figures. As he progressed, he simplified the compositions, depicting larger and fewer figures. He grew more comfortable working on a grand scale and relied less on preparatory cartoons. To expedite the process and reduce costs, he even devised an innovative mobile scaffold himself.

Metaphorically, the entire vault can be seen as a celebration of the human body, emphasizing its strength, beauty, and expressive potential. Michelangelo explored various poses, highlighting every muscle as if sculpting in paint. The nude form was extensively examined in all its variations, while natural landscapes and architectural elements took a secondary role in the composition.

The colors employed by Michelangelo were vibrant, brilliant, and shimmering, adding to the overall visual impact of the frescoes.

A section of the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

A section of the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Here is the list of subjects depicted by Michelangelo on the vault of the Sistine Chapel.

Band in the center of the vault, from the altar toward the back wall: Scenes from Genesis.

God separates The light from the darkness

God creates the sun and the moon

God separates the earth from the waters

The creation of Adam

God creates Eve

Original sin

Noah's sacrifice

The universal flood

The intoxication of Noah

Outer bands of the vault:

Prophet Jonah

Prophet Jeremiah

Libyan Sibyl

Persian Sibyl

Prophet Daniel

Prophet Ezekiel

Cumaean Sibyl

Erythraean Sibyl

Prophet Isaiah

Prophet Joel

Delphic Sibyl

Prophet Zechariah

In the triangles at the windows: Ancestors of Christ.

In the four corners of the vault:

The punishment of Aman

The bronze serpent

David and Goliath

Judith and Holofernes

Interesting facts

Finding himself also painting vaults and domes with figures and figures above his head, Michelangelo often found himself working in uncomfortable positions. This gave him back pain and serious vision problems.

Selena Mattei

Selena Mattei