Vanessa Renoux, Sculpture of a woman's head, 2020. Sculpture, 73 x 15 x 15 cm.

Modigliani sculptor vs. Modigliani painter

Many great masters in the history of art have expressed their views on reality by experimenting with, both pictorial and sculptural art, just like Pablo Picasso, Umberto Boccioni, Max Ernst, Edgar Degas, Joan Miró and others. Despite the different technical approaches to the two disciplines, in most cases where the same artist has engaged in multiple projects, he has oftentimes manifested the existence of an unambiguous, well-defined, and linear worldview, just as the Modigliani "case" exemplifies. In order to make manifest what has just been stated, it will suffice to compare Woman's Head (1912), one of the Tuscan's best-known sculptures, with the celebrated pictorial masterpiece entitled Elvira with a white collar, (1917), while also taking into consideration a work "halfway" between these two techniques, such as the caryatid Red Bust (1913). Regarding the sculpture dated 1912, it is important to open a small parenthesis, aimed at highlighting how between 1911 and 1913, the Leghorn artist devoted himself mainly to sculpture, inspired by the example of the Romanian Brancusi, a master Amedeo met in Paris. Despite Modigliani's predilection for the latter art, he could only devote himself to it for the aforementioned period, as the powders that were produced during the creation of the sculptures were deleterious to his tuberculosis. Returning to Woman's Head, the work, like most of the artist's sculptures, may have been anticipated by the execution of a preparatory drawing, probably consisting of sharp, incisive lines, which, mainly symmetrical, would be partly associated with architectural stylistic features. Subsequent to the design, the sculptural material was generally worked by the Leghorn, in order to generate studied solutions, which, made by clear-cutting, were clearly against the trend of the more widespread casting technique. Briefly describing the stylistic features of the aforementioned masterpiece, which pertain to Modigliani's sandstone work on a general level, Woman's head presents a tapered face seemingly unfinished, as it is sketched on an unpolished surface, on which a thin nose, oval eyes without pupils, a narrow chin, and a thin, cylindrical neck stand out.

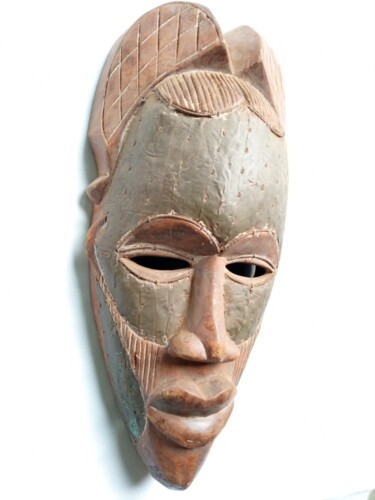

Amedeo Modigliani, Woman's head, 1912. Sculpture, 68.3 × 15.9 × 24.1 cm. MET: New York.

Amedeo Modigliani, Woman's head, 1912. Sculpture, 68.3 × 15.9 × 24.1 cm. MET: New York.

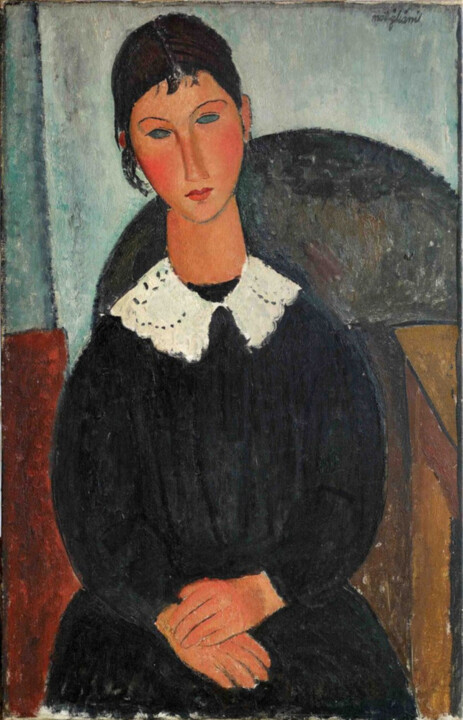

Amedeo Modigliani, Elvira with a white collar, ca. 1917. Oil on canvas, 92 x 65 cm. Paris: Jonas Netter Collection.

Amedeo Modigliani, Elvira with a white collar, ca. 1917. Oil on canvas, 92 x 65 cm. Paris: Jonas Netter Collection.

Such stylistic features also characterize the Caryatids series, which, made beginning in 1912, investigates the aforementioned classical theme through the use of both sculptural and pictorial art. In fact, the very Red Bust of 1913, created through the application of oil colors on cardboard, reveals a profound link between the two techniques, found in the stylized, synthetic and frontal figure of the protagonist, which features an extremely elongated face and neck. On the other hand, speaking of a later masterpiece, the link between pictorial and sculptural creation is repeated in Elvira with a white collar (1918), an oil portrait of a young woman, who, seated in the center of a room, is captured as she is intent on staring at the viewer with her blind eyes. It is precisely in this context that the stylized, tapered faces of the Italian master emerge once again, and he has worked hard to generate a new canon of beauty. At this point a question arises: from what were Modigliani's particular stylistic features inspired? The Leghorn artist knew how to give voice to that "wind" of African influences, which, spread in the Paris of his time, also animated masters such as Picasso and Brancusi, who "exemplified" their stylistic features, taking their cues from more synthetic and primitive exotic viewpoints. As a result, Amedeo's elongated and stylized faces can be interpreted as a kind of "updating" of the more traditional African masks, to which examples drawn from Cycladic, Sumerian, Egyptian, and Greek art dear to the Tuscan were also integrated.

Claude Grand, Hellen, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 70 x 50 cm.

Claude Grand, Hellen, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 70 x 50 cm.

Daniel Gomez, Homage to Modigliani #1, 2021. Concrete on other support, 58 x 21 x 18 cm / 18.00 kg.

Daniel Gomez, Homage to Modigliani #1, 2021. Concrete on other support, 58 x 21 x 18 cm / 18.00 kg.

Focus: the influences of African art.

At the end of the 19th century, the rationality of positivism was being replaced by an impetus aimed at greater emphasis on a more genuine return to spirituality, symbolism, and the deep manifestations of the human soul. Such an aesthetic and philosophical context deeply impressed the artists of the Paris School, who, like Picasso, Modigliani and Matisse, identified precisely in exotic art a means through which to express a return to a more genuine spirituality and introspection. Consequently, both Africanism and exoticism in general were promoted by the aforementioned, who saw them for the first time as authentic forms of artistic expression, now far from being mere works of cultures to be colonized. Certainly, such important innovation of aesthetic canons, was favored by the contact the artists had with the nineteenth-century institution of the Trocadero Museum, a place where the African masks so celebrated by Picasso were kept. Although it seems clear that African art has exerted a fundamental role in the development of Western figurative culture, also found in later movements such as Modernism and Die Brücke, its function is still little known and valued. In order instead to pay homage to this important primitivism, it is worth highlighting the impact that, to this day, Modigliani's Africanism exerts on Artmajeur artists, such as, for example Sibilla Bjarnason, Helen She and Anna Zhuleva.

Sibilla Bjarnason, Modigliani revisited, 2018. Collage / acrylic on canvas, 99 x 81 cm.

Sibilla Bjarnason, Modigliani revisited, 2018. Collage / acrylic on canvas, 99 x 81 cm.

Sibilla Bjarnason: Modigliani revisited

Sensuality lies, more than in a naked body, in the possibility of imagining it as such, referring to all those features, which, in our personal conception of beauty, we find attractive. Fascination is also conferred by the observation of a simple strip of bare skin, which might entice the observer to continue, in his or her head, the narrative of taking off our clothes. These concepts seem to animate with eroticism the languid female figure immortalized by the brush Sibilla Bjarnason, an artist, who, in the title of the work itself, makes clear reference to Amedeo Modigliani, crowning him as the reference point of her figurative investigation. In fact, in the character of the artist in Artmajeur, a reinterpretation of Nude seating on a sofa' , an oil painting by the Tuscan master made in 1917, is evident. In addition, precisely on the subject of the female body, it is important to recall how Amedeo's first solo exhibition, dated 1917, had female nudes as its subject matter. In fact, the event, organized by art dealer Léopold Zborowski at the windows of Berthe Weill's gallery, saw the exhibition of a number of undressed female bodies, which, decidedly far from the conventional canons of the time, aroused the most general indignation. This sentiment culminated in the arrival of law enforcement officials, who asked Weil to lower the shutters because the women depicted displayed, inexcusably for the time, hair on their bodies.

Helen She, Pop Modigliani, 2021. Acrylic / marker / collage on linen canvas, 50 x 70 cm.

Helen She, Pop Modigliani, 2021. Acrylic / marker / collage on linen canvas, 50 x 70 cm.

Helen She: Pop Modigliani

The Modigliani myth also lives again in the work of Helen She, where the Pop stylings of the remake dated 2021 transform a well-known masterpiece of art history, such as Reclining nude (on the left side) (1917), into the more commercial stylized image of a sinuous "soubrette" of our times. Probably, the simplification suffered by Pop Modigliani's protagonist, perhaps alluding to the modern high capacity of image reproduction, is also aimed at celebrating an easier and faster "accessibility" to art world icons. In fact, Reclining nude (on the left side) itself is known to be the largest nude of a woman made by Modigliani, a master who lavished himself on the representation of female awareness, eschewing the more mere illustration of mere muses. Despite the intensity of the multiple female figures attributed to Amedeo, the only woman with whom the artist ever had a more lasting connection was Jeanne Hebuterne, who, being "owned" by the Italian's heart, never appears without veils. Therefore, it is impossible to imagine Amedeo's companion in the provocative pose of the model in Reclining nude (on the left side), whose "unscrupulousness" is also excised from the intense glance she gives the viewer.

Anna Zhuleva, Pop art Modigliani portrait, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 80 x 60 cm.

Anna Zhuleva, Pop art Modigliani portrait, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 80 x 60 cm.

Anna Zhuleva: Pop art Modigliani portrait

The stylistic features of Pop art reinterpret, through their typical and extensive backgrounds of vivid colors, another masterpiece of art history signed Amedeo Modigliani, having for subject Jeanne Hébuterne, the woman he loved most. The portrait with the hat in question, dated 1918, is part of a series of works dedicated to his companion, a muse whom Amedeo portrayed in a variety of ways, but always with the aim of making her appear as a timeless figure with an elongated face and a melancholy gaze. The Italian artist's intent is to elevate such a woman to the ideal of feminine beauty par excellence, so much so that, on some occasions, he even allows the viewer to discover her pupils. It is well known that Modigliani actually only completed the eyes of the effigies whose souls he knew, so that the "seeing" Jeanne allows us to understand the depth of their bond. Unfortunately, such intensity would result in tragedy, as, after Amedeo's death, the woman, at the age of only twenty-two and pregnant, threw herself from the fifth floor of a building, as she was unable to bear the separation of the greatest and only love of her life.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli