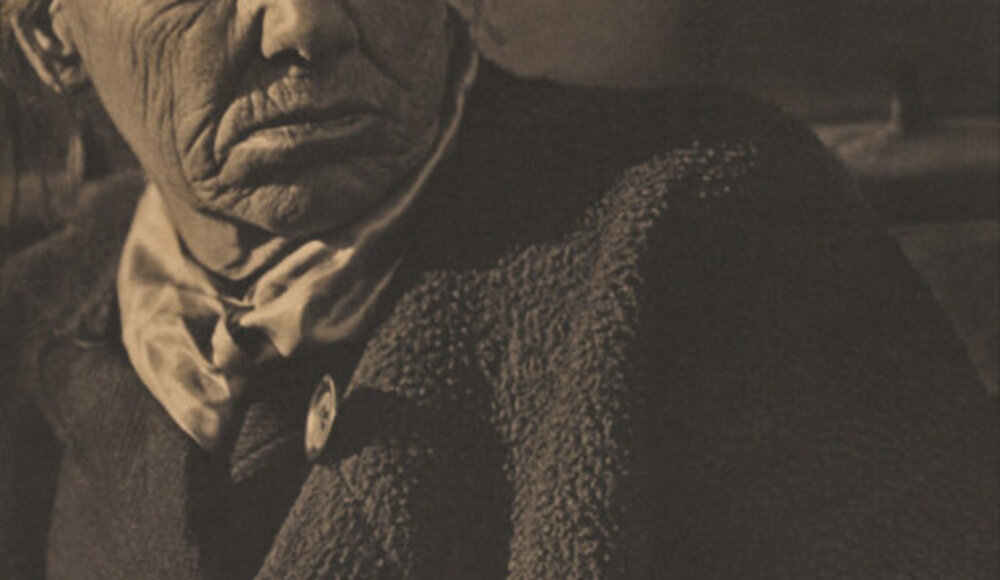

Paul Strand by Alfred Stieglitz (1917), via Wikipedia.

Paul Strand by Alfred Stieglitz (1917), via Wikipedia.

Who was Paul Strand?

Paul Strand (October 16, 1890 – March 31, 1976) was an influential American photographer and filmmaker. He played a pivotal role, alongside notable modernist photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston, in establishing photography as a recognized art form during the 20th century. In 1936, Strand was one of the founding members of the Photo League, a cooperative of photographers united by shared social and creative objectives. Over the course of his six-decade career, Strand produced a diverse and extensive body of work, capturing various genres and subjects across the Americas, Europe, and Africa.

Life

Paul Strand, originally named Nathaniel Paul Stransky, was born on October 16, 1890, in New York. His parents, Jacob Stransky and Matilda Stransky (née Arnstein), were Bohemian merchants. At the age of 12, his father gifted him a camera. On January 21, 1922, Strand married the painter Rebecca Salsbury. He frequently photographed her, often in intimate and tightly framed compositions. After divorcing Salsbury, Strand married Virginia Stevens in 1935. They divorced in 1949. He then married Hazel Kingsbury in 1951, and they remained married until his death in 1976.

Around the time Strand left for France, his close friend Alger Hiss was facing a libel trial, and they maintained correspondence until Strand's death. While Strand himself was never an official member of the Communist Party, many of his collaborators were either party members (such as James Aldridge and Cesare Zavattini) or prominent socialist writers and activists (like Basil Davidson). Several of his friends were also either Communists or suspected of being so, including Member of Parliament D. N. Pritt, film director Joseph Losey, Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid, and actor Alex McCrindle. Strand had close involvement with Frontier Films, one of the more than 20 organizations identified as "subversive" and "un-American" by the U.S. Attorney General. When asked in an interview why he decided to go to France, Strand mentioned that at the time of his departure, "McCarthyism was becoming rife and poisoning the minds of an awful lot of people."

During the 1950s, Strand insisted that his books be printed in Leipzig, East Germany, reportedly due to the availability of a printing process that was not accessible in other countries. This decision led to his books initially being banned in the American market due to their association with communism. Following his move to Europe, declassified intelligence files obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, which are now preserved at the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, revealed that Strand was closely monitored by security services.

Paul Strand, Portret, Washington Square Park (1917), via Wikipedia.

Paul Strand, Portret, Washington Square Park (1917), via Wikipedia.

Photography

During his late teenage years, Paul Strand studied under the guidance of renowned documentary photographer Lewis Hine at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School. It was during a field trip with Hine's class that Strand first visited the 291 art gallery, which was operated by Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen. The exhibitions of modernist photographers and painters held at the gallery deeply influenced Strand, prompting him to take his photography hobby more seriously. Stieglitz played a significant role in promoting Strand's work, showcasing it in the 291 gallery, featuring it in his photography publication Camera Work, and incorporating it into his own artwork in the Hieninglatzing studio. Some of Strand's early work, such as the well-known photograph Wall Street, explored formal abstractions, which influenced artists like Edward Hopper and his distinct urban vision. Other works by Strand reflected his commitment to using photography as a means of advocating for social reform.

When taking portraits, Strand employed a unique technique. He would mount a false brass lens on the side of his camera while simultaneously using a hidden working lens concealed under his arm. This allowed him to capture candid shots without his subjects being aware that their picture was being taken. While some criticized this method, it became a characteristic aspect of Strand's approach. He was one of the founders of the Photo League, an organization of photographers dedicated to using their art to promote social and political causes. Strand and Elizabeth McCausland were particularly active members of the league, with Strand assuming the role of an influential figure. Both Strand and McCausland were clearly aligned with left-leaning ideologies, with Strand displaying strong sympathy towards Marxist ideas. They, along with Ansel Adams and Nancy Newhall, contributed to the League's publication, Photo News.

Over the following decades, Strand expanded his creative pursuits into motion pictures alongside still photography. His first film, Manhatta (1921), also known as New York the Magnificent, was a silent film depicting the daily life of New York City, created in collaboration with painter and photographer Charles Sheeler. Manhatta included a shot reminiscent of Strand's famous Wall Street photograph from 1915. During 1932 to 1935, Strand resided in Mexico, working on Redes (1936), a film commissioned by the Mexican government that was released in the US as The Wave. He also contributed to other films such as the documentary The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) and the pro-union, anti-fascist film Native Land (1942).

Between 1933 and 1952, Strand did not have his own darkroom and relied on the facilities of others to develop his photographs. In December 1947, the Photo League was included on the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations (AGLOSO). In 1948, CBS commissioned Strand to contribute a photograph for an advertisement titled "It is Now Tomorrow." The photo depicted television antennas atop buildings in New York City. On January 17, 1949, Strand signed a statement in support of Communist Party leaders who were facing the Smith Act trials. Alongside other notable individuals such as Lester Cole, Martha Dodd, W.E.B. Dubois, Howard Fast, and Joseph H. Levy, Strand expressed his solidarity with figures like Benjamin J. Davis Jr., Eugene Dennis, and William Z. Foster.

In June 1949, Strand departed from the United States to showcase his film "Native Land" at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in Czechoslovakia. Afterward, for the remaining 27 years of his life, he resided in Orgeval, France. Despite not learning the language, he led an impressive and creative life with the assistance of his third wife, fellow photographer Hazel Kingsbury Strand. During this later period, although Strand was renowned for his earlier abstract works, he returned to still photography and produced some of his most significant pieces in the form of six book "portraits" of different places. These include "Time in New England" (1950), "La France de Profil" (1952), "Un Paese" (which featured photographs of Luzzara and the Po River Valley in Italy, Einaudi, 1955), "Tir a'Mhurain / Outer Hebrides" (1962), "Living Egypt" (1969, co-authored with James Aldridge), and "Ghana: An African Portrait" (with commentary by Basil Davidson; 1976).

Some photographs

Paul Strand, Wall Street (1915), via Wikipedia

Paul Strand, Wall Street (1915), via Wikipedia

Wall Street (1915)

Wall Street holds great historical significance, both in Paul Strand's body of work and in the development of photographic art. It marked a distinct departure from Strand's previous style of soft-focused Pictorialism, which involved using the camera and darkroom techniques to create images resembling the less fashionable painting style of the time, as judged by modernist standards. This photograph serves as an early example of Strand's inclination to combine elements of documentary realism and abstraction within the same composition.

On one hand, Strand presents the viewer with an objective and straightforward depiction of a street scene, capturing pedestrians walking while their elongated shadows are cast by the sun. On the other hand, the image displays a high-contrast interplay of light and darkness, as the shadows formed by the recesses of the imposing Morgan Trust Bank building create a slanted geometric pattern.

In contrast to his contemporaries like Alvin Langdon Coburn and Karl Struss, who focused on capturing activity and movement in their urban images, Strand took a more deliberate approach. He often directed his attention towards slower movements and static scenes. Notably, with Wall Street, Strand was surprised that he managed to capture such a sharp image of the moving individuals, considering the relatively slow processing time required for the photographic plates. It is said that Edward Hopper became captivated by this photograph and incorporated some of the same formal techniques into his own paintings.

Porch Shadows (1916)

During the summer of 1916, Paul Strand spent his vacation at a rented cottage in Twin Lakes, Connecticut. Influenced by the European avant-gardes, particularly the Cubists, Strand had already come to the realization that "All good art is abstract in its structure." Intrigued by the question posed by European painters regarding the nature of a picture, the relationships between shapes, and the filling of spaces, Strand embarked on an exploration. He used ordinary objects from everyday life, such as kitchen furniture, crockery, and fruit, and employed his large plate camera to elevate these mundane items into pure two-dimensional patterns.

The resulting collection of photographs included some of the earliest instances of purely abstracted images in the field of photography. One such example is Porch Shadows, which epitomizes Strand's approach. Upon closer examination, we might discern that the object depicted is nothing more than a regular round table placed on a porch. However, Strand alters our perception by first rotating the image. The geometric shapes that emerge—thin stripes, parallelograms, and a large triangle—are created by the interplay of light and shadow produced by the intense sunlight streaming through the slats of the terrace window.

Blind Woman, New York (1916)

Strand held the belief that capturing authentic urban portraits in a discreet manner was not only crucial but also morally justifiable. He aimed to contribute something meaningful to the world without exploiting the subjects in the process. This early portrait, initially published in Camera Work, was taken in Five Points, the impoverished immigrant neighborhood in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and reflects Strand's socialist and artistic mission. The photograph portrays a solitary woman in a medium close-up shot. A hand-painted sign hangs around her neck, indicating her blindness, while a numbered badge on her black smock identifies her as a licensed newspaper vendor. Although her gaze is directed outside the frame, the image reveals that she remains unaware of the close proximity of the camera, despite her blindness. To capture such captivating portraits, Strand employed a strategy where he rigged his camera with a false lens pointing forward, while the actual working lens was concealed at a ninety-degree angle under his arm, out of the subject's sight.

Geoff Dyer, in his influential book "The Ongoing Moment" examining photographic trends, suggested that the off-center pupils of the blind woman reflected Strand's own unconventional lens setup. Furthermore, Dyer proposed that the blind subject represented the desired invisibility sought by the photographer himself. Despite practical and ethical complexities, Strand maintained that the purpose of portraiture was to convey the presence of the photographed individual to others, leaving a lasting impression. This photograph quickly became an icon of the emerging American photography movement, blending the humanism of social documentation with the bold and simplified forms of modernism, as acknowledged by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The Lusetti Family, Luzzara, Italy (1953)

The Lusetti Family photograph represents Paul Strand's later period, after he had resettled in Europe. It is featured in his book titled "Un Paese, Portrait of an Italian Village," published in 1955. This photograph signifies a notable departure from his American portraiture, such as the "Blind Woman, New York," as his subjects now posed specifically for Strand's camera. Strand had been invited by Cesare Zavattini, a Neorealist screenwriter, to visit Luzzara, his agricultural hometown in the northern Po River Valley of Italy. Upon being accepted into the Luzzara community (Strand stood in the central town square every day until they became accustomed to his presence), he spent two months photographing the village and its inhabitants, which had once been a stronghold for anti-fascist resistance. Angela Secchi, a young farmer's daughter and one of his subjects, later recounted her experience: "He [Strand] took a large hat from my uncle's head and placed it on mine. Then he took my uncle's scarf and an old, crumpled smock, and instructed me to wear it over my dress. He wanted me to appear like a poor country girl." This contrived depiction of village life, catering to the tourist's gaze, contrasted with Strand's "Straight" aesthetic.

It was Cesare Zavattini's responsibility to provide the accompanying text that would infuse Strand's images with their socio-political significance. The Lusetti family portrait features a mother and five of her eight sons, all of whom were veterans of World War II. Their vacant and pained expressions hint at a shared experience of trauma. However, the true meaning of the image becomes apparent when we learn that four of the mother's children had died in infancy. Furthermore, her husband, the boys' father, a local communist partisan, had been brutally beaten by Fascist assailants on two occasions before ultimately losing his life while in active service. An unfortunate irony of the project was that only one thousand copies of the book were produced and sold at a high price. Angela Secchi later recalled, "People were amazed because the book cost the same as a bicycle," making it unaffordable for the modest budgets of the villagers.

Anna Attinga Frafra, Accra, Ghana (1964)

In his final installment of geographical series, Paul Strand traveled to Ghana where he spent three months between 1963 and 1964 photographing the country and its people. With the cooperation of President Kwame Nkrumah at the time (who was later ousted), Strand embarked on the project. However, the book titled "Ghana: An African Portrait," which featured a companion text by Africanist scholar Basil Davidson, was not published until 1976, four years after Nkrumah's death.

The objective of Strand's project, as described by African Studies scholar Zachary Rosen, was to present Ghana as "a new African nation with a population ready for industrial growth." Simultaneously, Strand aimed to showcase his respect for Ghana's heritage by employing a series of juxtapositions. These pairings included images of technological and economic progress alongside depictions of traditional and natural environments. Strand believed that the role of a documentary photographer was to capture the lives of ordinary people. He expressed, "The people I photograph are honorable members of the human family, and my concept of a portrait is to present someone who can be recognized as a fellow human being, with all the qualities and potentialities one can expect from people worldwide."

This humanistic philosophy is evident in his portrait of a young student named Anna Attinga Frafra. She is portrayed wearing a white sleeveless shirt against a plain white wall. Plant fronds intrude from the left side of the frame, but the viewer's attention is drawn to the three textbooks she carries atop her head. When Rosen stated that Strand successfully avoided producing "patronizing anthropological photographs," this particular image likely exemplifies his intention. It captures the personality of a subject who came to represent progressive thinking and an independent African state.

Percé Beach, Gaspé, Québec (1929)

In 1929, Paul Strand embarked on a trip to Canada accompanied by his wife, Rebecca Salsbury. During this journey, he captured a landscape that came to be known as Percé Beach. While it fulfills the primary criteria of a landscape photograph, there are aesthetic connections to Strand's iconic Wall Street photograph, which he had created twelve years earlier. Instead of a building, however, the dominant element in this photograph is a large body of water. The cliffs, entering from the left side of the frame, cast their shadows over the sea, replacing the pavements seen in Wall Street.

In an intriguing statement, Strand discussed color in his photography, despite working exclusively in black and white. He often used tinted papers that simulated the atmosphere of the location where he was shooting. For Percé Beach, he employed papers with cold blue tones, matching the ambiance of the scene. Additionally, Strand was fascinated by the concept of how spaces are filled. He believed that achieving a balance between weight and air in the photograph was crucial to its composition. The weight is conveyed through the darker tones present in rocks, roofs, and boats, while the notion of air is depicted through the light in the sky and its reflection on the water's surface.

Strand's commitment to portraying the lives of ordinary people can also be observed in this photograph. In the lower foreground of the frame, there is a narrative centered around workers. We see small figures, in this case, "dwarfed" by the forces of nature instead of man-made architecture, engaging with a large fishing boat. It remains unclear whether they are preparing to set sail or are in the process of mooring the vessel. However, the photograph leaves no doubt about the boat's significance in their lives and livelihoods.

Native Land (1942)

With his film Native Land, Paul Strand aimed to shed light on the violations of civil liberties in America during the 1930s. The focus of the film was primarily on the erosion of the Bill of Rights, which faced threats from corporate entities. These corporations employed spies and contractors to undermine and dismantle labor unions. Native Land, co-directed by Strand and Leo Hurwitz, who was a member of the Communist Party and later blacklisted, served as both a call to action for workers and a reminder of their constitutional rights. The film featured narration by the prominent African-American singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson.

Described as a "semi-documentary" or "docu-drama," Native Land blended real newsreel footage, including scenes from the infamous Memorial Day massacre of 1937 where ten striking protesters were killed by the Chicago police, with a fictional narrative. The fictional storyline depicted the subjugation and murder of sharecroppers whose union had been infiltrated by spies. In line with Strand's artistic and ideological perspective, Native Land aimed to challenge the conventional narrative style prevalent in classical Hollywood cinema. It shifted the portrayal of ordinary American laborers from subordinate or comedic roles to becoming the central heroes driving the plot.

Upon its release, Native Land was acclaimed as one of the most impactful and thought-provoking documentary films ever made by influential New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther. However, unfortunate timing played a role in its reception. The film was released shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, a time when the country sought unity and had little appetite for socio-political self-examination.

Legacy

In 1984, Paul Strand was honored with induction into the International Photography Hall of Fame (IPHF). The endorsement for his induction praised his ability to capture the everyday world with precision and truth. While some may debate whether Strand should be solely credited as the architect of Straight Photography, there is no denying that his work played a significant role in fostering the belief that only a camera could depict the world with such intricate detail, clarity, and purity. In the hands of a skilled photographer, it demonstrated that photography could hold its own within the broader modernist movement.

In his book, "The Photograph," scholar Graham Clarke suggested that Strand should be grouped with Stieglitz and other 'Straight' photographers associated with the f/64 Group, such as László Moholy-Nagy, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans, Robert Capa, Ansel Adams, and Edward Weston. According to Clarke, this select group of photographers contributed to the notion that the modern photographer was an inspired philosopher who transformed mundane reality into something new and ideal.

However, what set Strand apart from his peers was his endeavor to blend the philosophical aspects of Straight Photography with a strong socio-realist approach. He rejected the romanticized vision of the modern artist as a virtuosic genius. In his 1946 obituary for Stieglitz, Strand spoke not as an individual artist but as part of a collective that included fellow activists like Abbott, Zavattini, historian Basil Davidson, film director Joseph Losey, and poet Hugh MacDiarmid. Strand's legacy can best be summarized in his own words: "We realize, as perhaps he [Stieglitz] did not, that the freedom of the artist to create and share their work with the people is intrinsically linked to the fight for the political and economic freedom of society as a whole."

Key concepts

Strand held the belief that photography as an art form should transcend the creation of staged and idealized images, a practice known as Pictorialism, which was despised by modernists. He acknowledged that the camera possessed a unique advantage over other visual arts, as it could capture a singular moment in time and space with unparalleled precision, unlike what could be achieved by hand or in real-time. His Straight Photography, therefore, presented the purest and most authentic path towards a deeper and more genuine photographic experience.

Influenced by the formalist approach and cubist paintings of Cézanne, Braque, and Picasso, Strand became fascinated with the notion that photographic images could be deconstructed compositionally. In Straight Photography, he utilized large format cameras to produce images with striking contrasts, minimal depth (appearing two-dimensional), semi-abstract elements, and geometric repetitions. These images relied on their size and surrounding context to have their complete impact, often intended to be displayed on the revered white walls of specialized photography galleries.

While many artists in his circle adhered strictly to the "art-for-art's-sake" doctrine, Strand had a broader perspective. He believed that art should have the ability to connect with the viewer on both a spiritual and social level. As a result, he became associated with the notion that fine art can, and should, incorporate both abstraction and realism simultaneously. This meant that within a single photograph or documentary film, elements of both abstraction and realism could coexist harmoniously.

Summary

The history of modern art demonstrates that America provided a fertile environment for many significant pioneers in twentieth-century photography. Among them, Paul Strand stood out with a distinct position. Strand is often recognized as the originator of "Straight Photography," a pure style of photography that used large format cameras to capture and present new perspectives on ordinary or previously overlooked subjects as fine art. Strand's 'Straight' approach was so influential that it was embraced by other prominent photographers, including the members of the f/64 Group who shared similar ideals with Strand. Over the following decades, many other Straight photographers also adopted this aesthetic. However, Strand went further by expanding the 'Straight' style into the realm of documentary photography. He gained high regard and became a leading figure for those seeking social and political change through both still and motion pictures.

Selena Mattei

Selena Mattei