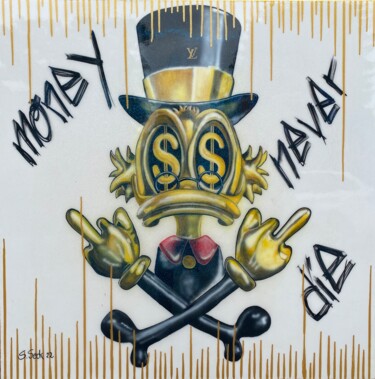

Tony Rubino, Rubino money calling gangster entrepreneur Christmas, 2022. Painting, acrylic / lithography on canvas, 50.8 x 50.8 cm.

Tony Rubino, Rubino money calling gangster entrepreneur Christmas, 2022. Painting, acrylic / lithography on canvas, 50.8 x 50.8 cm.

To talk about money, or simply take the trouble to flaunt it in a showy and elitist manner, it is not necessary to open your mammoth wallet in front of the bus stop in order to flaunt the renowned American Express Centurion Card to your waiting neighbor. In fact, it is possible to allude to your most absolute state of affluence through multiple less direct and "vulgar" expedients. It is precisely the art world that provides us with some interesting food for thought, in that, before arriving at Warhol's stylized representation of the American dollar, it made explicit, through the depiction of richly dressed subjects, placed in glorious interiors and surrounded by symbols alluding to ease, princely living conditions. All this, was implemented with great class, rejecting the more contemporary, albeit mocking and ironic, attitude of ostentation of trappers, subjects capable of shoving the green means of their wealth in people's faces, not to mention other body parts. In any case, not to defend the latter, it is obligatory to say that each era has known its own forms of manifestation of wealth, which remain, at present, subjective, relative and immeasurably multiple. Leaving aside more contemporary trends, in order to return to mentioning the aforementioned topical, as it has been understood by the more traditional history of art, it is obligatory to refer to two italian masterpieces, aimed at immortalizing two illustrious women, just as they were intent on flaunting magnificent specimens of preciousness, allusive to their majestic lineage: Agnolo Bronzino's Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni (1545-46) and Sandro Botticelli's Portrait of a Young Woman (1475). About the first oil on panel, it is good to highlight how, the identity of its youngest effigy, was unveiled and made official, only in 1949, that is, when the Art Historian Luisa Becherucci, referring to the ancient words of the famous Giorgio Vasari, recognized in the Duchess's chaperone the descendant Giovanni. In this context it seems legitimate to ask: how did the Bronzino have the opportunity to come into contact with, and immortalize, such celebre nobility, even becoming the court painter of Cosimo I? The latter Duke, an able procurer of talent, could not miss Bronzino's genius, which he had the opportunity to test in the realization of the frescoes in the chapel of Eleonora in the Palazzo Vecchio, which can be dated between 1541 and 1545. Returning to the "rich," very rich ($$$), portrait in question, it necessarily had to do justice to the rank of Eleonora of Toledo, a Spanish noblewoman and daughter of the viceroy of Naples, who was the first wife of the aforementioned Cosimo I de' Medici, second and last duke of the Florentine Republic and, later, first grand duke of Tuscany, a role she exercised until her death, which occurred in 1574. In the circa 1545 masterpiece, considered to be one of the highest expressions of 16th-century Florentine Renaissance portraiture, Eleonora di Toledo is seated frontally as she flaunts all her financial ease, without arming herself with waving "big bucks", bottles of Champagne, fancy cars and extravagant banquets, but wearing, in a very sober, serious and elegant manner a precious gown decorated with the finest damask embroidery, accompanied by a fine pearl necklace, which encircles her chaste cleavage with two turns.

Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo, c. 1545. Oil on panel, 115 × 96 cm. Florence: Uffizi Gallery.

Bronzino, Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo, c. 1545. Oil on panel, 115 × 96 cm. Florence: Uffizi Gallery.

The realistic rendering of this luxury, which gives us all the idea of its precious manufacture, is due to Bronzino's Mannerist style, aimed at bringing to life figures, as well as details, of great exactitude and sharpness of outline. Another masterpiece of art history, also enriched by the sumptuous presence of pearls, which in this case even come to multiply, taking different locations on the support, is the aforementioned Portrait of a Young Woman (1475) by Sandro Botticelli. However, before delving into the mere description of the aforementioned luxury, it is good to unveil what is, to this day, considered to be the most probable identity of the effigy, who, presenting somatic traits similar to Venus (1482-85), Spring (c. 1848) and Ideal Lady (1475-1480), made by the Tuscan master, could indeed be, on this occasion as well, Simonetta Vespucci. The latter, nicknamed the "peerless one," represented one of the most celebrated noblewomen of the Florentine Renaissance, whose unparalleled beauty featured in the works of many artists of the time, although, only with Botticelli did she, according to the gossip of the time, also forge a dubious emotional bond. Since, however, the undisputed object of our attentions is not the charm of this woman, but her money, let us come to the point, describing how, in the three-quarter pose in which Vespucci has been portrayed, the masterpiece of 1475 enhances a showy medallion she wears around her neck, probably the reverse copy of an ancient heirloom, in which the features of Apollo and Marsyas are reproduced. In addition, the preciousness of such a jewel might even be increased if, as many sources suggest, it would have previously belonged to Lorenzo de' Medici. The girl, not content with this pageantry, wasted, who knows my how much time, arranging her thick hair into a sophisticated hairstyle, within which a variety of pearls were woven, culminating in a complex, richly decorated headdress. Finally, the richness narrated by art history did not spare the viewer access to the most luxurious interiors, such as, for example, those described in Archdukes Albert and Isabella visiting a collection (c. 1621-1623) by Jan Brueghel and Hieronymus Francken II and in Family Portrait of Louis XIV with Madame de Ventadour (8th century) by Nicolas de Largilliere.

Botticelli, Portrait of a Young Woman, 1475-1480. Frankfurt: Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

Botticelli, Portrait of a Young Woman, 1475-1480. Frankfurt: Städel Museum, Frankfurt.

In conclusion, if you now think that wealth is something pertaining exclusively to the world of the living, you are sorely mistaken! In fact, the vanitas genre has often accommodated, alongside eerie skeletons, dead animals and spent candles, gaudy jewelry. In the latter context, exemplified by Brueghel Jan the Younger's still life, titled Still Life with Cup and Vase of Flowers and Box with Jewels (ca. 1620), the truest moral essence of the genre emerges, aimed at making us think that: subsequent to our demise, it will be the skeleton who will make himself beautiful with our jewels, enjoying for eternity what we have earned with the sacrifices of a lifetime. After these latest disturbing revelations, contemporary art retorts, proposing lighter subjects aimed at celebrating the "god" money, through unprecedented viewpoints well exemplified by the work of Artmajeur artists such as, Esteban Vera, Art Vladi and Dominik Rutz.

Wo$H, B86516208A, 2022. Painting, spray paint / acrylic / marker / resin / collages on MDF Board, 85 x 85 cm.

Wo$H, B86516208A, 2022. Painting, spray paint / acrylic / marker / resin / collages on MDF Board, 85 x 85 cm.

Esteban Vera, Money, 2019. Painting, Acrylic / spray paint on canvas, 90 x 110 cm.

Esteban Vera, Money, 2019. Painting, Acrylic / spray paint on canvas, 90 x 110 cm.

Esteban Vera: Money

Vera's painting, as explicated by the artist himself, immortalizes the icon of the most famous and best-selling board game of all time, namely Monopoly, personified by a sleek mustachioed little man, who, initially called Rich Uncle Pennybags, literally the rich uncle with the bag full of coins, finally took on the appellation Mr. Monopoly in 1999. The features of the well-known character, devised by cartoonist Dan Foz, drew inspiration from the famous financial tycoon John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913), who similarly used to conceal himself behind a thick mustache, sections of a beard at his time extremely fashionable. Mr. Monopoly, together with the great celebrity the game has collected, has become, over the years, a veritable star, so much so that in 2006 Forbes included him in its list of the 15 richest fictional characters of all time, placing him ahead of Bruce Wayne, i.e., the extremely wealthy businessman behind the Batman mask. Having come to this point, the question arises: how did the world of Monopoly enter art? Was there perhaps an forerunner, which favored the creation of the original and unprecedented work of the artist from Artmajeur? The answer is affirmative! The progenitor of the spread of this Monopoly-themed art subject is Alec Monopoly, a man generally masked with a bandana and hat, but strictly armed with a spray can, who has now become a golden kid of contemporary street art. His works, which are among the most sought-after all over the world, however, have a "nefarious" origin: the artist began depicting Mr. Monopoly because, at the height of the financial crisis in 2008, he wished for a return to Wall Street prosperity, spending much of his time devoting himself precisely to Monopoly's monetary "positivism."  Art Vladi, Money, 2016. Painting, acrylic on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Art Vladi, Money, 2016. Painting, acrylic on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Art Vladi: Money

Vladi's painting, titled Money, directly alludes to that sort of paper "gasoline," aimed at fueling all the movement of our world, to the tune of "strumming" wallet openers and closers. Within the figurative narrative, however, the mention of the "god" money occurs through a simple inscription, which finds its place above the gaping jaws of a crocodile, surrounded by a colorful background covered with other "tags." Is all this context meant to allude to a certain aggressiveness, inherent in the man who lends himself to big money deals? Such a hypothesis could be justified, first of all, by the gaping mouth of the dinosaur's oldest cousin, together with the presence of tags, intended to allude to achieving the best version of ourselves, undoubtedly achievable through prosperous earnings. In any case, the "pressure" captured so far could also be interpreted with less intensity, precisely by reflecting on the fact that, the crocodiles themselves remain open-mouthed even when relaxed, in order to stabilize their body heat. As far as art history is concerned, on the other hand, the combination of crocodile and money, particularly luxury goods, has come to fruition, in a more "realistic" way, in Tyler Shields' iconic photo titled "Gator," a shot, which, present in multiple variants, immortalizes an alligator intent on snatching a woman's purse out of her hand, alluding to all the fragility and precariousness in which the lifestyle of the wealthy is immersed.

Dominik Rutz, Style break #1 money, 2022. Painting, resin / lacquer / pigments on wood, 70 x 50 cm.

Dominik Rutz, Style break #1 money, 2022. Painting, resin / lacquer / pigments on wood, 70 x 50 cm.

Dominik Rutz: Style break #1 money

Rutz's painting repurposes an unidentifiable number of banknotes, which, superimposed one on top of the other, seem to allude to such wealth that the pictorial support is extremely reduced and inadequate to contain them. This attack is answered by the wood itself, which, by staining itself red and hosting an x in its lower right part, seems to rebel against the hegemony of the dollar, pointing to it for what it really is: bearer of wars, blood and selfishness. After these personal interpretations, it is a must to refer to something more concrete, namely the popular artists in art history who, like Rutz, have used money within their artistic investigation, such as, for example, Mister E and David LaChapelle. The former is an American artist known for his creative use of $100 bills, which he hopes to convert, from icons of evil, to healthier bearers of ambition. In fact, referring to Mr. E's own words he reveals, "Through my work, I want to show the beautiful side of money. Money represents freedom; it should inspire people to work hard and motivate everyone. Money can allow people to have the freedom to do what they choose, to be charitable, to live without stress." Speaking of LaChapelle, on the other hand, The American photographer and video artist, primarily famous for his hyper-realistic, highly saturated and often controversial editorial portraits of celebrities, has tackled the "god" money in his "Negative Currencies" series. The latter investigates dollars, euros, etc., turning them into a kind of a negative photographic film, in which both sides of the bills are visible at the same time. Such expedient is used by the artist to make people think, as, while beautiful and bright, his banknotes should remind them how money is the main cause of speculation in the world we live in.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli