Gérard Capron, Harlequin, 2020. Acrylic on linen canvas, 65 x 54 cm.

Gérard Capron, Harlequin, 2020. Acrylic on linen canvas, 65 x 54 cm.

Harlequin: where does his iconography come from?

In 1888-90 Paul Cézanne painted the Harlequin, in 1901 Pablo Picasso made the Thoughtful Harlequin and in 1919 Juan Gris immortalized the Harlequin with guitar. These are just some of the most famous interpretations of a topic, which has been widely exploited by artistic investigation between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But have you ever wondered about the reasons behind the popularity of this character? Moreover, where does his iconography come from? The answers lie both in the carnival festival and in the "Commedia dell'Arte", traditions that, between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, met and mixed. In fact, Harlequin, who first became part of the repertoire of the fixed types of the "Commedia dell'Arte", later also influenced the masks of the carnival.

Gabriel Baptiste, Carnival night, 2009. Oil on linen canvas, 81 x 65 cm.

Gabriel Baptiste, Carnival night, 2009. Oil on linen canvas, 81 x 65 cm.

The historical interlacement: carnival and "Commedia dell'Arte"

The carnival, a popular feast all over the world, finds its most remote origins in the celebrations of the Greek Dionysia and the Roman Saturnalia, even if, in its modern form, it recalls more the medieval events during which, in order to honor the free movement of spirits, human beings had to "lend" their bodies, hiding behind masks. The most ancient documented carnival, even more similar to the modern versions, is instead the one of 1094, which took place in Venice, in an atmosphere of public entertainment marked by mockery and masks. Just starting from this last city, the above mentioned tradition spread all over Italy, distinguishing itself, in every region, for typical characteristics and peculiarities. From the second half of the sixteenth century, however, the masks of the carnival underwent a strong contamination, welcoming within them the new characters of the "Commedia dell'Arte". This last theatrical genre, born in Italy in the mid-sixteenth century, spread throughout Europe and remained in vogue until the mid-eighteenth century, boasts medieval origins, dating back to the time when jesters and acrobats entertained the public during festivities and carnival. In fact, it was precisely these jesters who, towards the sixteenth century, transformed these performances into a real profession, becoming professionals who were welcomed into the new paid theaters. The theatrical representations of the "Commedia dell'Arte" were distinguished by the peculiarity of not following a script, but outlines or scenarios, which traced the guidelines of each character, who drew on his repertoire of phrases and improvised sayings. Finally, another characteristic was the use of masks, which were at the origin of the fixed types of each company, having their own repertoire of actions and attitudes, aimed at facilitating the understanding of theatrical representations and the recognition of the character. These masks also indelibly influenced those of the carnival, which, as a type of festivity, was perfectly akin to hosting the protagonists and typical "Commedia dell'Arte" jokes.

Serg Louki, Harlequin, 2020. Watercolor on paper, 30 x 40 cm.

Serg Louki, Harlequin, 2020. Watercolor on paper, 30 x 40 cm.

Harlequin: Iconography and Character

Officially, Harlequin is a mask of the "Commedia dell'Arte", dating back to the 16th century and originating in Lombardy (Italy), more precisely in the city of Bergamo. In reality, however, the history of this character is much broader, varied, ambiguous, discordant and controversial, since it probably also appeared in Greek and Latin culture, in medieval Nordic fables and in the tradition of France in the V century. In addition, the fact that Harlequin was often interpreted as a figure of diabolical origin, operating in the legends of almost all European states, inexorably compromised its origin. Therefore, it was only after the introduction of this mask into the "Commedia dell'Arte" that it became definitively associated with Italian culture, becoming the symbol of the cunning, foolish, thieving, lying and cheating servant, in perpetual conflict with his master and constantly concerned with obtaining the money necessary to appease his insatiable appetite. Regarding the iconography, Harlequin's face, originally similar to the snout of an animal, a monster or an evil being, was traditionally hidden by a black mask and a forked white cap, whose shape is intended to allude to his ancient diabolical horns. The multicolored tights, instead, probably obtained from the patches of his family's clothes or received as a gift from friends on the occasion of the carnival, was worn to attract and mislead the foolish public. Another characteristic of the character was his stick, which was used to threaten and attack his rivals, in order to grab as much food as possible. With the passing of time, however, these characteristics were refined: the original patched tights were replaced by a multicolored dress with the characteristic and refined lozenge pattern and the original demonic features of the black mask were refined.

Xavier Froissart, Big red Harlequin, 1994. Oil on canvas, 130 x 97 cm.

Xavier Froissart, Big red Harlequin, 1994. Oil on canvas, 130 x 97 cm.

Harlequin: Contemporary Iconography

Like the great masters of the past mentioned above, also the artists of Artmajeur have found in Harlequin a fascinating subject, to be investigated in its many iconographic and character peculiarities, perfectly interpretable with originality, crossing new contexts and always unedited and captivating points of view. An example of this are the paintings made by Artmajeur's artists, Makovka, Henri Eisenberg and Livia Alessandrini.

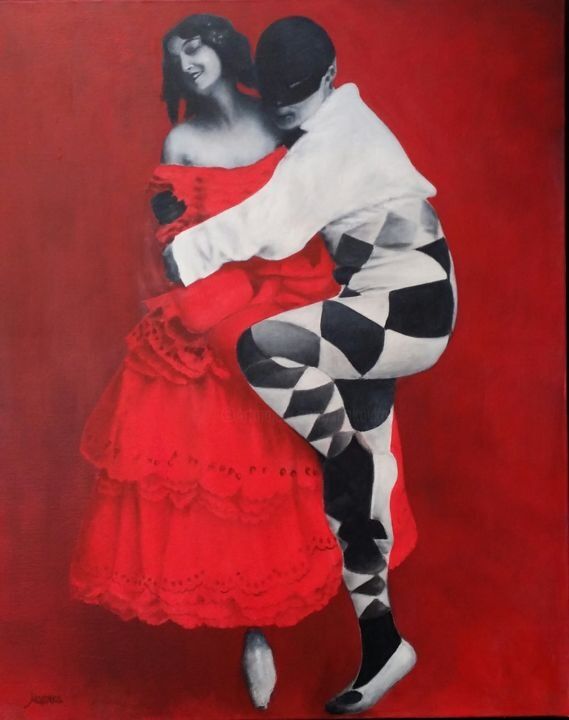

Makovka, Columbine and Harlequin, 2013. Painting, 92 x 73 cm.

Makovka, Columbine and Harlequin, 2013. Painting, 92 x 73 cm.

Makovka: Columbine et Harlequin

Makovka's painting nicely illustrates one of the most talked-about love stories of the "Commedia dell'Arte", namely that between Harlequin and Columbine. This lively, pretty, cunning, full of verve and quite a liar, has all the characteristics to impress the cheating servant, who, in fact, is often animated by a very strong jealousy towards her. Consequently, Makovka's artwork, in which Harlequin grasps his beloved with passion and lust for possession, appears to be totally in line with the tale of the "Commedia dell'Arte", even if the latter has undergone considerable restyling. In fact, the clothes, hairstyles and headgear of the characters have been made with a strong contemporary touch, in order to make a love story that has lasted for centuries current and eternal.

Henri Eisenberg, Harlequin on the bubble, or the height of lightness, 2015. acrylic on linen canvas, 46 x 33 cm.

Henri Eisenberg, Harlequin on the bubble, or the height of lightness, 2015. acrylic on linen canvas, 46 x 33 cm.

Henri Eisenberg: Harlequin on the bubble, or the height of lightness

In Eisenber's surreal painting, Harlequin, a cunning and trickster servant, finds himself operating in a new context, performing actions that are totally outside his character, that is, hovering on a soap bubble suspended in the air. The aforementioned, his face no longer concealed by the mask, faces the new challenge with a mocking grin, giving an example of his ability to adapt and survive, always accompanied by an ironic and friendly attitude that distinguished his character.

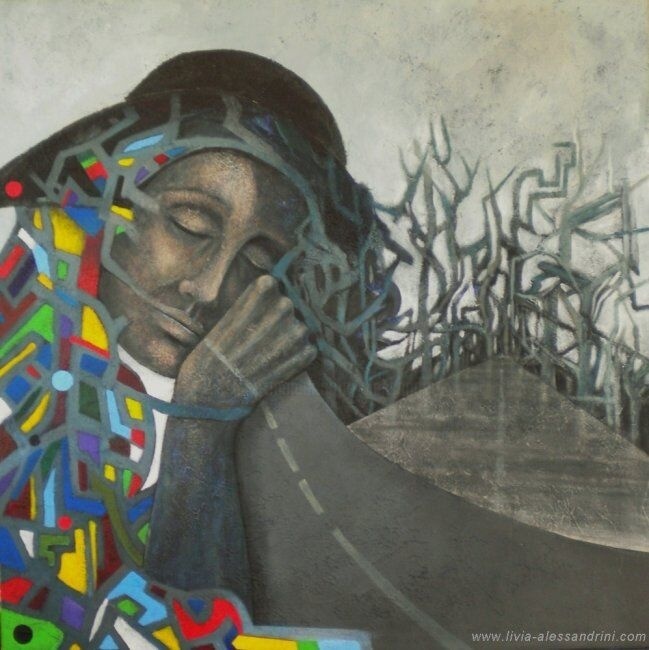

Livia Alessandrini, The road, 2010. Painting, 70 x 70 cm.

Livia Alessandrini, The road, 2010. Painting, 70 x 70 cm.

Livia Alessandrini: The road

In Livia Alessandrini's innovative and surreal painting, Harlequin abandons forever the context of the carnivalesque mockery, assuming an attitude that does not suit his character very well, such as that of rest, meditation and apparent reflection, accompanied by the accomplishment of a gesture that is actually impossible. In fact, the servant holds a road in his arms, while the contours of the trees stand out close to his giant face, recalling the gray lines that define the colors of his geometric dress. Such a dreamy and surreal atmosphere transmits us a great serenity, definitely replacing the playfulness that distinguishes the "Commedia dell'Arte".

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli