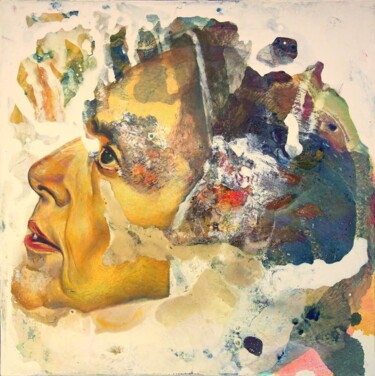

ARTEMISA'S MENINAS (2021)Painting by Rai Escale.

ARTEMISA'S MENINAS (2021)Painting by Rai Escale.

The top ten as a way of teaching art history...

When an art historian approaches the study of the work of a great artist, such as, in this specific case, Diego Velázquez, he or she analyzes, both his or her biography and pictorial production, approaching the latter by investigating it in chronological order, in order to record the progression and evolution of the point of view of the master in question. At the point, however, when the expert has to approach the amateur account of his subject of study, in order to make the subject in question attractive to the masses, it is advisable to divulge only the key and salient points of the above-explained lengthy research, sometimes inclusive of critical viewpoints and comparisons between artists that are quite complex, specific and detailed. In this light, the popularizing stratagem of the top 10 proves to be extremely effective, as the reader is certainly interested in the mere and simplified discovery of the artist's best-known works, although from reading the latter one cannot expect to acquire comprehensive expertise on the subject, as they are exempt from the necessary biographical and, chronologically speaking, stylistic introduction. Therefore, my top 10, as well as many others in circulation, will necessarily be introduced by a brief presentation of the Spanish master, capable of bringing out his stylistic peculiarities, etc., which will subsequently be recognizable through the observation of the ten works I have elected as progressive manifestos of Diego Velázquez's figurative investigation.

A VELAZQUEZ (2020)Painting by Felipe Achondo.

A VELAZQUEZ (2020)Painting by Felipe Achondo.

Diego Velázquez: 5 key points to understand him

Biographical: Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599-1660) was a Spanish painter, considered to be the leading artist in the court of King Philip IV, as well as one of the most representative masters of the Baroque era, within which he distinguished himself mainly through his practice of the portrait genre.

Painter's role: Diego Velázquez's main position was that of prestigious court painter for Spain's King Philip IV; in fact, during the Baroque period, he was paid to create works for royalty, although he maintained an extreme commitment to portraying people and scenes of everyday life as well.

Stylistic: Velázquez's portraits present an individualistic, naturalistic and direct style, which have led to the Spanish master being recognized as a precursor of Realism and Impressionism, capable of privileging authenticity over Romanticism and other modes, which, historical or somewhat traditional, were common at the time to deal with the pictorial genre in question. The artist's accuracy and painterly truth can be seen, among other things, in the depictions of his most typical details, noted for their multiple nuances, rendered by free and loose brushstrokes, as well as the use of gradients of light, color and form, which allowed him to bring portraiture and scene painting out of its stationary confines, crowning him as one of the most important masters of Spain's Golden Age.

Technical: noteworthy is the skill found in the Spanish master's practice of the chiaroscuro technique, by which is indicated that precise treatment of lights and shadows, which, extremely enhanced, give rise to high pictorial contrasts, having the purpose of highlighting particularly relevant points in the work, capable of also giving rise to a complex atmospheric perspective.

Compositional: Velazquez carefully studied the arrangement of subjects within his works, as he conceived of them as a strategic tool, capable of directing the viewer to grasp the peculiarities for which the masterpieces were intended. In order to render such intentions, the painter also used to make use of diagonal structures, complex focal points and separate planes, capable of manipulating the viewer's eye by leading it to the focal points of the work, where the deeper understanding of the work was realized.

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Sebastián de Morra, c. 1644. Oil on canvas, 106.5 cm × 81.5 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Sebastián de Morra, c. 1644. Oil on canvas, 106.5 cm × 81.5 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Portrait of Sebastián de Morra

Diego Velázquez: top 10 works of art

10. Portrait of Sebastián de Morra (1644)

The masterpiece in question, dated circa 1644, depicts Sebastián de Morra, a dwarf jester at the court of Philip IV of Spain, who has been depicted staring intently at the viewer, assuming a posture, probably intended to suggest a disguised intent of denucia parseguito by the Spanish master, who would perhaps have wanted to criticize the court's treatment of "little" jesters, who, since the medieval period, were hired by sovereigns as laughing-stocks and deformed entertainers. This rather contemptuous attitude would also be evidenced by the viewpoint taken toward such characters by court painters prior to Velázquez, who used to paint the subjects in question with the coldness, disregard, rigidity and, at times, contempt, that would be reserved for a kind of humanized domesticated animals. Contrary to this tradition, however, Velázquez immortalized the dwarves with extreme respect, as he believed that there was beauty in simply painting the truth, despite the fact that it might appear in the eyes of some to be unpalatable or at all standardized in its forms. In keeping with this point of view, the artist, instead of portraying the dwarves as mere deformed entertainers, highlighted the humanity of these subjects, which, at times, appeared to be far superior to that of other court figures immortalized. In this way, the innovative and sensitive Velázquez attributed to the dwarves the same humanity with which he used to paint the royal family, demonstrating how after getting to know several "little men," he was probably able to go beyond their appearance and simply recognize their human nature.

Diego Velázquez, Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan, 1630. Oil on canvas, 223 cm × 290 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Diego Velázquez, Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan, 1630. Oil on canvas, 223 cm × 290 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

9. Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan (1630)

Before Velázquez akin subject matter was immortalized by, among others, Giorgio Vasari, a celebrated Italian painter, architect and art historian born in 1511, who, in 1564, painted The Forge of Vulcan, a mythological masterpiece rich not only in messages and metaphors comprehensible within the cultured milieu of the Medici court, but also in a multitude of characters. The latter, embodied by workers intent on fidgeting, provide the backdrop for the encounter between Minerva and the god Vulcan, subjects who are executed in contorted poses typical of the Mannerism of the time. Well distinguished from the latter description is the later work by the Spanish master, who, with fewer characters arranged on the same plane, immortalizes the encounter between Apollo and Vulcan, referring to the episode in which the former of the two visited the latter in his forge in order to reveal to him that his wife Venus was the lover of Mars, god of war. Such a shocking confession can precisely be found in the expression Velázquez painted on Vulcan's face, which is gathered in a feeling, in which idignation and astonishment are skillfully mixed. This entire mythological context, in which the blacksmith's helpers who hear the "divine gossip" are also included, is told by the painter in a somewhat novel way, as it is rendered through stylistic devices capable of lowering an ultra-earthly episode into reality, just as if it were the scene of a bourgeois novel.

Diego Velázquez, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, 1618. Oil on canvas, 63 cm × 103.5 cm. National Gallery, London.

Diego Velázquez, Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, 1618. Oil on canvas, 63 cm × 103.5 cm. National Gallery, London.

8. Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (1620)

Captured in the foreground on the canvas support are Martha, that is, the young woman intent on pounding garlic in the mortar, likely engrossed in the preparation of a probable Spanish aioli sauce, who is accompanied by elderly woman palsied behind her, a place from which lends itself to indicate a scene that finds location in the opposite part of the painting, visible from a window, or a mirror. In the latter frame, Jesus, depicted seated, is captured in a didactic attitude that he addresses to Mary, as well as to an elderly woman who seems to want to interrupt the Master. The complex interplay of cross-references just described, which will find its fullest expression in Las Meninas, differs well from the simpler pyramidal construction of the same subject by Jan Vermeer, intended to come to life in a later masterpiece, i.e., dated 1656, in which the story is told, once again, of that Gospel episode of Jesus' visit to the home of Martha of Bethany and her sister Mary, which occurred while the former, representing the active life, was intent on household chores, when the latter, an exponent of the spiritual life, was concentrating exclusively on the activity of listening to Christ.

Diego Velázquez, Equestrian Portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares, c. 1636. Oil on canvas, 313 cm (123 in) × 239 cm (94 in). Museo del Prado.

Diego Velázquez, Equestrian Portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares, c. 1636. Oil on canvas, 313 cm (123 in) × 239 cm (94 in). Museo del Prado.

7. Equestrian Portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares (1634)

Velázquez's masterpiece, because of the characteristics found in its subject, falls fully within the genre of the equestrian portrait, that is, in that category of paintings or sculptures, aimed at showing subjects riding a horse, a peculiarity that has found its first expression since antiquity, so much so that the most famous example turns out to be the statue of Emperor Marcus Aurelius in Capitoline Square in Rome. In the case of the Portrait of the Count Duke of Olivares on Horseback, depicting Don Gaspar de Guzmán y Pimentel, prime minister of Philip IV of Spain, it is important to consider how, again, the work portrays the subject triumphantly on horseback, a pose that, however, at the time was generally reserved for monarchs, rather than for the office of the person in question. In spite of these inconsistencies, it is important to highlight how the prime minister was the object of the painter's attentions even later on, just as can be seen in a portrait from 1635, which, against a neutral background, depicts the Duke of Olivares, while adorned in a black suit with a white ruff, presenting a rather tired and swollen face, apparently aged in comparison to the equestrian masterpiece of the year before. It was probably politics that aged him, as it is well known how he, during his tenure, worked to adopt fiscal and administrative reforms, but without much success...

Diego Velázquez, Dwarf with a Dog, Ca. 1645. Oil on canvas, Height: 142 cm; Width: 107 cm. Royal Collection (New Royal Palace, Madrid).

Diego Velázquez, Dwarf with a Dog, Ca. 1645. Oil on canvas, Height: 142 cm; Width: 107 cm. Royal Collection (New Royal Palace, Madrid).

6. Dwarf with Dog (1640-45)

Dwarf with Dog, an oil on canvas from the Prado, depicts a court jester, who, richly dressed and upright, is flanked by the cumbersome presence of a mastiff, whose bulk underscores the modest height of the main figure, who, most likely, leashes the larger animal with some apprehension. The dwarf in question, identified by many as the court jester Don Antony "the Englishman," or with fellow countryman Nicholas Hodson, takes us into the "cult" that art history has reserved for these figures since the earliest centuries, so much so that in ancient Egypt many votive statuettes of dwarves,which, within shrines, were intended to embody the fertility cult, have been found in addition to skeletons with dwarfism. In addition, dwarves were often depicted in the tombs of the elite of the time, as dancers and dancers, musicians, royal attendants, jewelers, attendants of various kinds. It was, however, from the Renaissance onwards that these characters reached the height of their popularity, becoming a veritable status symbol, since, for the lords of European courts, it was a sign of prestige to flaunt this type of adviser or lady-in-waiting. An example of this is the recurrence with which, during the 16th century, within the Florentine court of Cosimo I dè Medici, the now iconic dwarf Morgante was depicted. Finally, coming to the era of the Spanish master, in addition to the portraits made by Velázquez himself, equally well known are the English portraits of Richard Gibson and Anne Shepherd; or that of Sir Jeffrey Hudson, the little servant of Queen Enrichetta Maria of France.

Diego Velázquez, Old Woman Frying Eggs, c. 1618. Oil on canvas, 100.5 cm × 119.5 cm. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Diego Velázquez, Old Woman Frying Eggs, c. 1618. Oil on canvas, 100.5 cm × 119.5 cm. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh.

5. Old Woman Frying Eggs (1618)

To understand Old Woman Frying Eggs, it is necessary to make a premise, briefly explaining what is meant by genre painting. The latter, part of the practice of genre scenes, encompasses all those works of art, aimed at capturing events taken from everyday life, a peculiarity that made it long considered inferior to historical-religious and portrait painting. Nevertheless, genre painting became widespread, mostly in the Netherlands and in the small format, starting in the first half of the 16th century, boasting the likes of Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Adriaen and Isaac van Ostade, David Teniers the Younger, Aelbert Cuyp, Johannes Vermeer and Pieter De Hooch. Returning to Diego Velázquez, the masterpiece in question, created during the artist's Sevillian period, depicts modest characters, personified by a woman cooking or frying an egg, illuminated, through a skillful use of chiaroscuro, by a light source coming from the left, capable of generating strong luminous contrasts, ready to shape even to the features of the second character: a boy who appears on the far left of the support. Both of the two phases of life in question, which take shape in the aforementioned subjects, have been forged by a somewhat photographic realism, capable of capturing with equal accuracy the tools of the trade, such as the plates, cutlery, pans, pestles, jugs and mortars of daily use.

Diego Velázquez, Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress, 1659. Oil on canvas, 127 cm × 107 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Diego Velázquez, Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress, 1659. Oil on canvas, 127 cm × 107 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

4. Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress (1659)

Maria Theresa of Habsburg (1638-1683), daughter of King Philip IV of Spain and Elizabeth of France, also known as Maria Theresa of Austria, is an extremely recurring subject within the work of Velázquez, who, in the case of the 1659 masterpiece in question, wished to portray her while wearing a very elegant blue dress, skillfully rendered by short strokes of pure color, now on view in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Prior to this work, however, the features of Maria Theresa as a child were immortalized in 1653 in Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Peach Dress and later in Portrait of the Infanta doña Margarita of Austria (c. 1665), as well as in The infanta Maria Theresa of Spain (1652), a fact that makes us wonder: to what is the popularity of this character due? In fact, the Spanish master had to focus on this subject on several occasions, as his portraits were sent to Vienna in order to be able to show the progressive maturation of the girl to Leopold I of Habsburg, the maiden's uncle to whom she had been betrothed.

Diego Velázquez, Venere Rokeby, 1648 ca. Oil on canvas, 122,5×175 cm. National Gallery, Londra

Diego Velázquez, Venere Rokeby, 1648 ca. Oil on canvas, 122,5×175 cm. National Gallery, Londra

3. Venus Rokeby (1648)

The masterpiece in question represents an authentic jewel of art history, in that it is the only nude, of the total four made by the artist, to have come down to us, through which, we can also attest to the stylistic debts that the Spaniard accrued from the example of works of similar subject, mainly made by Tintoretto, Titian and Rubens. In any case, the most plausible model would seem to be that of the Venus of Urbino (Titian), given the relaxed pose assumed by Diego's goddess, who, however, differs from the Italian master in having captured his model from behind, while she is intent on observing her image reflected in a mirror held by Cupid. It is precisely this latter figure that makes the identity of the protagonist, who, traditionally generally portrayed with light hair, now has thick dark hair, immediately recognizable. Finally, doing a bit of healthy gossip, the work, one of the last painted by the artist, seems to have used as a model the features of the young Roman painter Flaminia Triunfi, with whom the painter probably had an affair and perhaps even a son named Antionio Da Silva, whom he abandoned when, after his stay in Italy, he had to return to Spain at the king's request.

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Innocent X, c. 1650. Oil on canvas, 141 cm × 119 cm. Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome.

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Innocent X, c. 1650. Oil on canvas, 141 cm × 119 cm. Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome.

2. The Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650)

The Portrait of Innocent X was painted by Diego Velásquez borrowing a technique akin to that of Titian, in that the Spaniard constructed his subject from quick, fat brushstrokes, often, as in the case of the red mozzetta, also highly charged and poorly shaded. In any case, this is not the most relevant aspect of the painting, which, a manifestation of a perfect psychological study of the character, consecrated Velázquez as one of the greatest interpreters of portraiture of his time. In fact, The pontiff's face, oriented to the right but with his gaze pointed toward the viewer, presents eyes with a decisive and intense expression, which are accompanied in their revelation by the wrinkling of his eyebrows. Enriching what is described are the painted tight lips, which, together with the posture and the right hand, elegantly abandoned on the armrest, stand to allude to great ease and self-mastery. The pictorial description actually coincides with the real one, as Giovanni Battista Pamphili (1574-1655) was considered a man of rather difficult and reserved character, who was later also immortalized by Francis Bacon in his well-known Screaming Pope series. The latter, conceived from Velásquez's model, gave rise to a group of portraits in which the subject in question is revealed to the viewer as deformed and distorted, in order to re-present a metaphorical journey into the interiority of the individual and, at the same time, into the hell of existence.

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656 circa. Oil on canvas, 318×276 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656 circa. Oil on canvas, 318×276 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

1. Las Meninas (1656)

The multiple subjects present in Las Meninas, captured by the skillful brush of Diego Velázquez, appear brought together within one of the rooms of the Madrid Real Alcázar, that is, the residence of Philip IV, located in the Spanish capital, where the artist immortalized, as the pricipal character of his masterpiece, the daughter of the king's new wife: the Infanta Margarita Teresa. The latter appears surrounded by her ladies of the court, as well as other members of the latter, so much so that the painting even features a self-portrait of the painter, whose stable presence in the court of Philip IV works to create one of the most unforgettable illusions in the history of art: the viewer's attention is in fact initially captured by the figure of Marguerite and then, at a later stage, just after noticing the presence of the Spanish master, identifies with the subject the painter is engaged in portraying in his canvas. A more attentive eye, on the other hand, might become estranged in the detail of the mirror, in which Philip IV and Marianne become the undisputed protagonists, while a great many viewers would have the opportunity to wonder into the nature of the motion of the character immortalized on the staircase, the Cimabellan José Nieto, whose intention we will never know: to arrive or to leave the place portrayed forever.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli