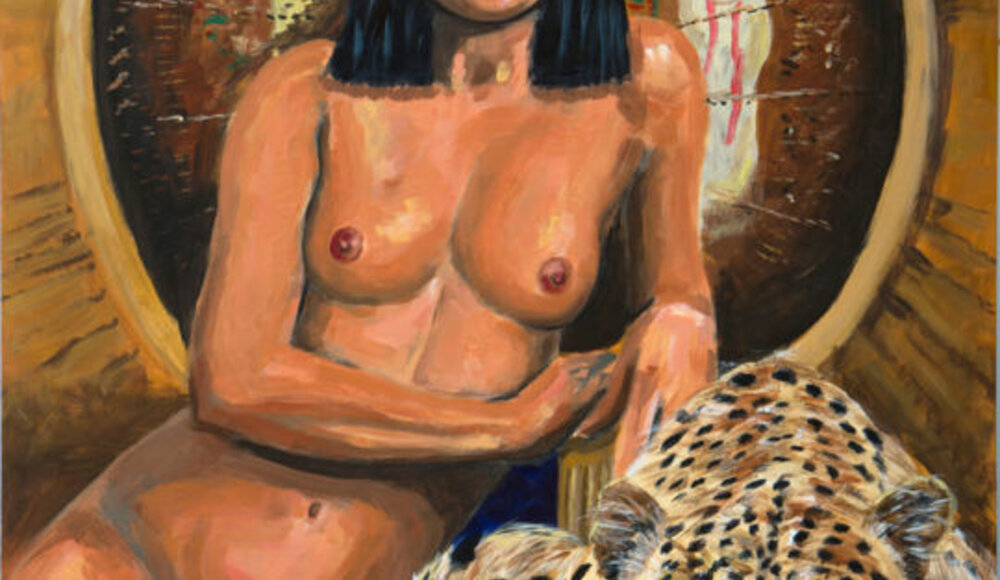

Pictor Mulier, Naked Cleopatra with her leopard, 2017. Acrylic on wood, 80 x 60 cm.

Pictor Mulier, Naked Cleopatra with her leopard, 2017. Acrylic on wood, 80 x 60 cm.

Albena Vatcheva, Cleopatre, 2021. Oil on linen canvas, 50 x 100 cm.

Albena Vatcheva, Cleopatre, 2021. Oil on linen canvas, 50 x 100 cm.

Cleopatra (69-30 BC), Egyptian queen and the last monarch of the Ptolemaic kingdom, is better known for her talents as a charmer than for her governmental talents, so much so that it was thanks to her charm, bestowed by her intelligence, personality and culture, rather than her beauty, that she ascended the throne for the second time, that is, when, after bewitching Julius Caesar, she succeeded in finally getting rid of her rival and brother Ptolemy XIII. However, the love affair between Rome and Egypt did not end with the death of the aforementioned politician, for, after Caesar's assassination, Cleopatra met and seduced the "victor of the East," Mark Antony, with whom she entered into a passionate affair, which ended in one of the most notorious and tragic tales in history. It is precisely such dramatic, legendary, poetic and passionate events that have made the figure of the queen extremely popular in art-historical circles, so much so that it is possible to reconstruct a figurative type of narrative, which, through the centuries, has been expressed through precise and recurring themes. Especially, since the Renaissance, pictorial works aimed at illustrating the life of the ruler have dealt with, presenting great affinities between them, such subjects: the death of Cleopatra, the banquet and the meeting with Antony, to which it is possible to add the less popular subjects of the landing at Tarsus, "feminism" and lust. Speaking of the death of Cleopatra, a subject already present in ancient frescoes, such as the one in the House of Joseph II in Pompeii (1st century), it is worth mentioning, this time within the post-Renaissance artistic investigation, Rosso Fiorentino's panel painting dated about 1525, a work that the Tuscan artist executed during his stay in Rome, where he came into contact with ancient statuary, which deeply inspired him. In fact, his Death of Cleopatra appears to be a "reinterpretation" of the Sleeping Ariadne, a statue now in the Vatican Museums (Rome), which, precisely because of its bracelet, was once identified as a depiction of the aforementioned queen of Egypt. The same story of the departure was narrated by an oil on canvas of about 1648, namely Guercino's Cleopatra dying, a work that, preserved at the Strada Nuova Museums (Genoa), presents a simple construction of the scene, within which the reduced chromatic range, lends refinement and monumentality to the figure of the queen, who appears sensually distended at the moment she is mortally bitten by an asp. Regarding the less popular subject of Cleopatra's landing at Tarsus, it is impossible not to refer to Claude Lorrain's oil on canvas dated 1642-43, which, preserved at the Louvre Museum, captures classical architecture, placing it in a landscape of pure invention, aimed at depicting the ancient port illuminated by a golden light, which catches the characters almost in counter light.

Rosso Fiorentino, Death of Cleopatra, c. 1525. Oil on panel. 94.7 x 73 cm. Braunschweig: Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum.

Rosso Fiorentino, Death of Cleopatra, c. 1525. Oil on panel. 94.7 x 73 cm. Braunschweig: Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum.

Giambattista Tiepolo, Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra, 1745-1748. Fresco. Venice: Palazzo Labia, Ballroom

Giambattista Tiepolo, Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra, 1745-1748. Fresco. Venice: Palazzo Labia, Ballroom

The theme of the banquet, on the other hand, is exhaustively exemplified by the work of Giambattista Tiepolo, major painter of the Venetian eighteenth century, who, in the oil Banquet of Antony and Cleopatra (1743), gave the latter the features of his wife Maria Cecilia Guardi, a woman he captures within one of the numerous banquets organized by the aforementioned lovers. In particular, the painting is meant to immortalize the precise moment when, in response to Antony, who claims to be able to offer the most expensive dinner, Cleopatra dips a precious pearl in vinegar in order to demonstrate her unbeatable wealth. The same master also interpreted another popular theme, aimed at portraying the queen of Egypt; in fact, between 1745 and 1748, he executed the fresco Encounter between Antony and Cleopatra, a work that was part of a pictorial cycle he created at the Ballroom of Palazzo Labia (Venice). In that masterpiece, Antony, wearing classical armor, is depicted in the center of the painting, while Cleopatra, who finds placement to the left of it, wears elegant and opulent 18th-century-made clothes. These protagonists, surrounded by other characters and animals, are placed within a staircase descending downward, in which the presence of classical architecture is imposed, taking shape through columns, pilasters, Corinthian capitals, a round arch and an architrave. Speaking instead of the late 19th century, it is at this moment in history, and more precisely in 1887, that an extremely innovative, "feminist," self-conscious and unprecedented interpretation of the aforementioned Queen is placed. In fact, in the English weekly The Graphic of the time, John William Watherhouse's Cleopatra, a woman, can be found among the twenty-one interpretations of female heroines, who, without corset and without shame, is intent on staring fixedly at the viewer, shamelessly provoking him. Finally, in this context of "female emancipation" is also another work of art, which is characterized by an even more self-conscious, explicit and erotic sexuality: the lustful Cleopatra by Hans Makart. It is precisely in this last masterpiece that the queen, set in a luxurious atmosphere, appears extremely sensual, allusive and intoxicated with pleasures.

Randa Hijazi, The Egyptian Monalisa, 2017. Acrylic / collage on canvas, 170 x 140 cm.

Randa Hijazi, The Egyptian Monalisa, 2017. Acrylic / collage on canvas, 170 x 140 cm.

Lubchik, Nefertiti ancient Egypt, 2019. Oil on canvas, 60 x 60 cm.

Lubchik, Nefertiti ancient Egypt, 2019. Oil on canvas, 60 x 60 cm.

Cleopatra tells the story of the women of ancient Egypt

Cleopatra is certainly an icon, that is, one of the most popular women in history, as well as in ancient Egypt, a civilization in which, however, there were a variety of models of femininity, including: Pharaoh women, such as, for example, Nitocris (6th Egyptian dynasty) and Nefrusobek (12th Egyptian dynasty); great royal brides, such as Tiy and Nefertiti; goddesses Isis, Hathor, Bastet and Sekhmet; and royal women, such as Diefatnebti and Meresankh I. Such richness is due to the fact that the Egyptian civilization, unlike many other ancient and modern peoples, while not recognizing social equality, upheld the essentiality of the complementarity of tasks intended for men and women, so that the latter were actually respected and valued, even if intended, when they were neither goddesses nor sovereigns, for the specific task of taking care of the family's prosperity. In this all-female context, the artworks of Artmajeur artists, just like some of the great masterpieces of art history, helped to celebrate the memory of the most famous and immortal Egyptian women.

Marta Zawadzka, Nefertiti, 2022. Acrylic, ink, oil, spray paint on canvas, 120 x 120 cm.

Marta Zawadzka, Nefertiti, 2022. Acrylic, ink, oil, spray paint on canvas, 120 x 120 cm.

Marta Zawadzka: Nefertiti

Nefertiti (c. 1370 BCE - 1330 BCE) was an Egyptian queen of the 18th dynasty, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten, consort with whom she was responsible for the creation of a new, henotheistic religion. The woman of "change" has been depicted in multiple paintings, reliefs, sculptures and drawings, among which, the oldest turn out to be the representations found within TT188 (Theban Tomb 188), i.e., one of the Tombs of the Nobles located in the area of the Theban Necropolis, situated on the west bank of the Nile, in front of the city of Luxor (Egypt). Despite the significance of this ancient find, the most popular work depicting the ruler is probably the Bust of Nefertiti, a portrait of the queen executed by Thutmose in about 1342 BCE, made of limestone covered with stucco and painted. This masterpiece, now housed in the Neues Museum in Berlin, has very realistic proportions and facial expression, in which the slender, long and elegant neck, the well-defined chin and a slight serene smile designed to illuminate an intense gaze stand out. In addition, the two halves of the face, which are extremely symmetrical, present a light-brown tinted pigmentation, where the lips, slightly more intense, stand out lightly. Finally, the woman presents, in addition to the traditional blue headdress, a quintessential Egyptian fashion must-have: the typical makeup made by applying Kajal around the eyes, still recognized as a hallmark of the Nile civilization. In this geographic and temporal context Zawadzka's contemporary painting is "placed," aimed at re-proposing, within a colorful and lively abstract background, the minimalist outline of the aforementioned sculpture, which finds new life in a context of twentieth-century derivation.

Jelena Petkovic, Cleopatra, 2018. Oil on linen canvas, 81 x 60 cm.

Jelena Petkovic, Cleopatra, 2018. Oil on linen canvas, 81 x 60 cm.

Jelena Petkovic: Cleopatra

Picking up on Petkovic's own words, the Cleopatra painting was created as an explicit homage to the fascinating and magnetic personality of the most famous ruler of ancient Egypt, who was depicted without referring to a particular event, but through a celebratory close-up portrait, aimed at making visible, in addition to the features of the rich effigy, multiple symbols of her civilization of belonging. In fact, among the emblems depicted, a papyrus sheet, having the purpose of alluding to wisdom, and the Ankh, a cross symbolizing life, which Cleopatra clutches in her left hand, stand out blatantly. In addition, geographical references are also found within the work, as the fluttering of the sovereign's dress is reminiscent of the waves of the Nile, while intense rays of sunlight illuminate a pyramid in the background. Within the history of art, another woman has portrayed Cleopatra; in fact, in an oil on canvas of 1620, Artemisia Gentileschi portrayed the sovereign, who, in this case more lascivious and dramatic, is deprived of any royal attributes, presenting herself as a simple woman. Finally, this character is placed by the Italian artist within a dark environment, where it is also possible to glimpse, if one pays close attention, the presence of an asp, the animal that was the cause of the legendary death of the aforementioned.

Edgar Garces, Nefertary / the nubian goddess, 2019. Digital photograph on canvas, 180 x 120 cm.

Edgar Garces, Nefertary / the nubian goddess, 2019. Digital photograph on canvas, 180 x 120 cm.

Edgar Garces: Nefertary / the nubian goddess.

Nefertari (1285 B.C.E. - 1255 B.C.E.), great royal bride of Ramesses II, was one of Egypt's best-known and most powerful rulers, having an influence comparable to that of Nefertiti and Cleopatra, although she did not reign independently. Probably, her celebrity is also due to the fact that she was able, both to read and to write, skills that, during her time, were truly exceptional. Precisely through these talents, she was able to maintain a lively correspondence with other rulers of her time, using her knowledge in the service of diplomacy. Her appearances are knowable through the contemplation of the wall paintings present at QV66, or the tomb of Nefertari, which, having its location in the Valley of the Queens in Egypt, was discovered in 1904 by Ernesto Schiapparelli, an Italian Egyptologist and historical director of the Egyptian Museum in Turin. In the contemporary context, the features of the ancient queen are revived through the Pop art narrative of Garces, whose photography makes explicit reference to the figure of Nefertari in order to allude to the serenity of the most ancient human nature, a peculiarity highly desirable for the future of the world.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli