Art De Noé, Tribute Basquiat, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 70 x 70 cm.

Art De Noé, Tribute Basquiat, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 70 x 70 cm.

“Hollywood Africans”

"I don't think about art while I'm working. I try to think about life."

Basquiat's words perfectly summarize the point of view taken by his artistic investigation, which, rich in multiple symbols and meanings, often at first glance concealed by "crude" and "unfocused" stylistic devices, pursued the goal of offering the viewer an "objective," and sometimes "dramatic," cross-section of the society in which the American writer and painter lived and practiced, synthesizable, in part, by the richness of the content gathered in the 1983 painting entitled Hollywood Africans. In fact, the latter masterpiece, part of the permanent collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, represents a courageous and sincere denunciation of the ways in which African Americans were represented in the entertainment industry of the time, highlighted, first and foremost, by the very title of the painting, which, in a concise and direct way, juxtaposes the two main terms of "comparison" and "confrontation." Within the canvas, on the other hand, the aforementioned story is told by referring to an episode from the same year, which saw the artist, already famous in New York and beyond, as the protagonist of a trip to Los Angeles, during which, accompanied by the rap musician Rammmellzee and the graffiti artist Toxic, he stopped off in Hollywood, where the three friends, in addition to admiring the footprints of movie stars, had their pictures taken in a photo booth. It is precisely the latter image that has been reproduced, as a sort of "synthetic trinity," in Hollywood Africans, where the aforementioned faces find their place within a yellow background, which, replete with highly symbolic and allusive writing and drawings, is somewhat reminiscent of the walls of our suburban streets. Unlike urban reality, however, in which the multiple graffiti refers to different messages, Basquiat's masterpiece refers to a single social theme, having the purpose of denouncing how the white elite of the film world of the time had blatantly stereotyped black actors. In fact, the annotations "TOBACCO," "SUGAR CANE," and "GANGSTERISM" indicate the prevailing "ghettoization" of African-American people into specific roles within the entertainment world of the 1980s, to which the artist wants to ideally rebel by also bearing the date 1940, which, written at the top of the painting, probably refers to the year that actress Hattie McDaniel became the first African American to win an Oscar, for playing the racial caricature of "Mammy" in Gone with the Wind (1939). Finally, the story of the bitter prejudice narrated by the masterpiece continues through the presence of allusive erased inscriptions, which were deliberately "removed" by the artist in order to make them even more visible, as it is well known how our attention lingers more on what is less easy to read, reach or interpret.

Serge Berezjak, The bird, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 110 x 85 cm.

Serge Berezjak, The bird, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 110 x 85 cm.

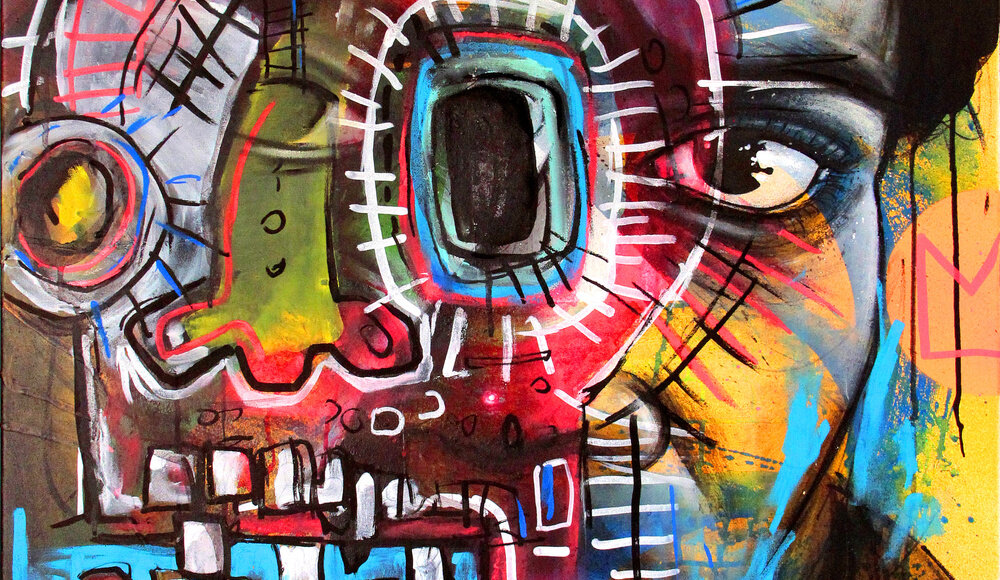

Pol Attard, Black anger, 2018. Acrylic / pencil / pastel on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Pol Attard, Black anger, 2018. Acrylic / pencil / pastel on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Basquiat's Symbolism

However, Basquiat's symbolism is not exhausted in the aforementioned narrative, as there are additional, significant and recurring images in his work, which, having become a hallmark of his personal research on reality, are well exemplified in the frequent depiction of human bodies, crowns, boxers and heads (or skulls). About the first type of symbolic representation, it is good to highlight how Basquiat's interest in anatomy is Leonardo-derived, despite the fact that his bodies are paradoxically meant to criticize the excessive presence of the human figure within art history. In regard to the three-pointed crown, however, this iconic and extremely recurrent motif in the American artist's work most likely alludes to fame, wealth, power, and royalty. When the latter ornament rests on the head of certain figures, on the other hand, it is meant to indicate the artist's propensity to recognize such figures as authorities, that is, as alternative models in stark contrast to the more canonical ones imposed by society. Finally, when the crown finds placement on the head of the painter himself, he wants to refer to his ambition, determination and perseverance, qualities having the purpose of leading him to the attainment of notoriety and respect from artistic society. As for boxers, these figures tell the story of the fascination African American athletes exerted on Basquiat, a love that is made explicit through the creation of prominent and muscular figures, realized through celebratory marked lines and expressive colors. Finally, the heads painted by the painter turn out to be highly representative of the identity, and in particular the origins, of the artist himself, as they are evocative of those African masks, which, previously fetishized by masters such as Picasso, return to represent a more genuine cultural recuperation.

Patrick Santus, Think stupid, 2007. Acrylic / colored pencils / chalk / pencil / ink / charcoal / gouache / marker / crayon / ballpoint pen / gel pen on canvas, 150 x 150 cm.

Patrick Santus, Think stupid, 2007. Acrylic / colored pencils / chalk / pencil / ink / charcoal / gouache / marker / crayon / ballpoint pen / gel pen on canvas, 150 x 150 cm.

Pol Attard, Captive, 2020. Acrylic / spray / marker / collages on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Pol Attard, Captive, 2020. Acrylic / spray / marker / collages on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Basquiat's impact on the art world

Speaking of the relationship between Basquiat and the art of his time, it is well known how the American master, among the most important exponents of graffiti art, also associated with neo-expressionism, quickly came to success, becoming a protagonist of the vibrant New York art scene, where, between the late 1960s and the 1980s, he managed to "transfer" graffiti from the most disparate urban contexts to museum halls. The relevance of the creative flair of the aforementioned painter continues to be felt within contemporary art, expressing itself through the work of artists, who, animated by the same impulse of denunciation, strongly desire to give voice to the unresolved dramas of racism and marginalization. Indeed, we can take as an example the work of the well-known Bansky, who, in 2017, on the walls adjacent to the Barbican center in London, created Boy and Dog, a graffiti against racism inspired by Basquiat's Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump (1982). Finally, it is worth pointing out how references to the latter master's artistic investigation continue in the production of other contemporary artists, such as, for example, Aboudia and Huma Bhabha, as well as in the work of Artmajeur painters, as evidenced by the works of T. Angot, Spaco and Stan.

T. Angot, Human evolution, 2022. Acrylic / spray on canvas, 81 x 65 cm.

T. Angot, Human evolution, 2022. Acrylic / spray on canvas, 81 x 65 cm.

T. Angot: Human evolution

Just as stated by the artist himself, Angot's production turns out to be indelibly marked by the influence exerted by three iconic artists, namely Picasso, Basquiat and Miro. Speaking of Human evolution, this acrylic on canvas reveals the interpretive modalities of the example drawn from Basquiat's lesson, evidently manifested in the inscriptions, the crown and the "stylized" man, which find location, predominantly, in the right side of the work. With regard to the latter figure, it appears to represent an original and topical remake of the crowned character of Grillo, that is, one of the two protagonists of Basquiat's 1984 painting. These figures, arranged in the first and third artwork's panels, forcefully impose themselves in the viewer's vision, ideally decreeing themselves as the emotional protagonists of the narrative. In reality, however, Grillo rejects a cohesive interpretation, since the viewer, in order to understand the meaning of the painting, must necessarily move around the work, becoming aware of all its parts, even the more abstract ones. Similarly, the eye of the observer of Human evolution must take in both the more realistic and the more "stylized" parts of the work, merging them into a single intent: to spread the variety of artistic experimentation, the result of human evolution itself.

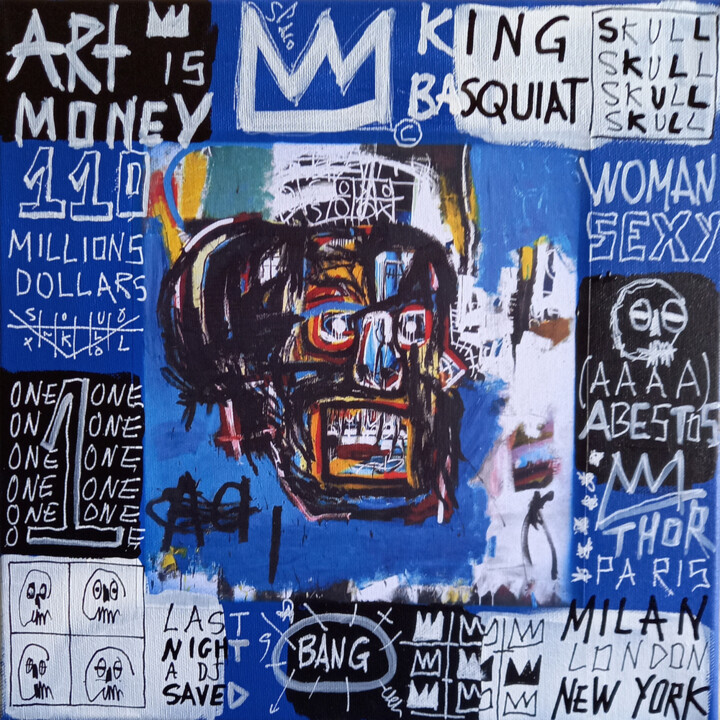

Spaco, Spaco 110M Basquiat, 2022. Collages / acrylic on canvas, 30 x 30 cm.

Spaco, Spaco 110M Basquiat, 2022. Collages / acrylic on canvas, 30 x 30 cm.

Spaco: Spaco 110M Basquiat

Spaco's work represents an original remake of Untitled, Basquiat's 1982 painting, which, in this 2022 version, is enriched with an unprecedented "frame" of lettering and crowns, aimed at celebrating, and summarizing, the American master's most popular stylistic features. Returning to Untitled, the masterpiece, sold in May 2017 by Sotheby's for $110.5 million to Japanese businessman and art collector Yusaku Maezawa, represents one of the American master's many powerful images of giant skulls made by the American master, which, having the peculiarities of repeatable icons as logos, have become one of Basquiat's artistic symbols par excellence. In addition, the impact and replicability of such a kind of memento mori, seems almost to make note of the force with which, in the artist's time, graffiti, previously intended only for defaced subway walls or bathroom stalls, made its way into the art world.

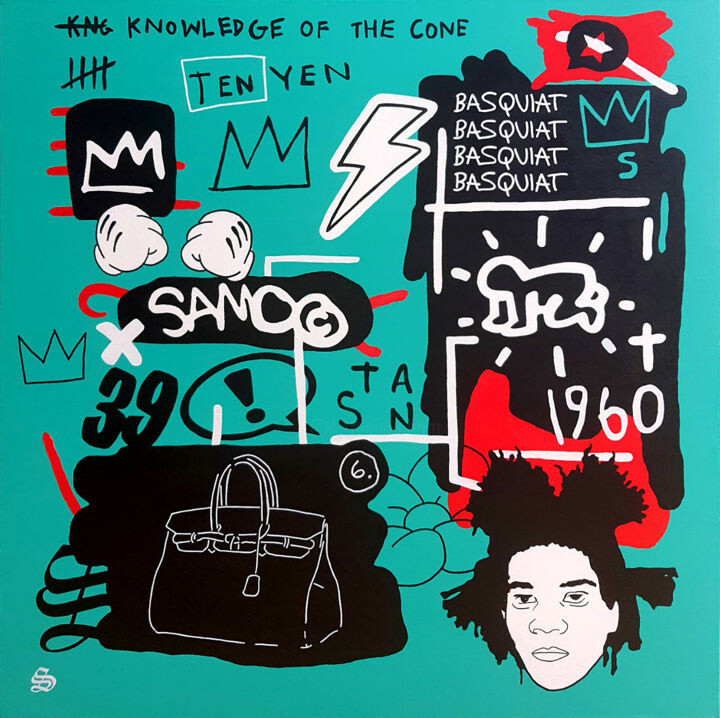

Stan, Basquiat by Stan, 2021. Acrylic / marker on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Stan, Basquiat by Stan, 2021. Acrylic / marker on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

Stan: Basquiat by Stan

Stan's painting is inclusive, just like Basquiat's works, of multiple messages, images and, consequently, symbols and allusions. In fact, one arranges on the canvas: Basquiat's portrait, probably Basquiat's year of birth (1960), some crowns, the SAMO tag, some writing, erased lettering, Miki Mouse hands, and Keith Haring's Radiant Baby. About the SAMO writing, this abbreviation of the words "Same Old Shit" was the pseudonym under which Basquiat and writer Al Diaz tagged in New York from 1978 to 1980. In fact, it was in the late 1970s that this tag began to spread through Soho and Tribeca, where, enriched with the copyright symbol, it also became famous for being accompanied by catchphrases, which, seemingly meaningless, represented a way of poking fun at the false beliefs fed by society. Despite their popularity, this pair of writers, whose admirers included Keith Haring, parted ways in 1980, that is, when Diaz made it explicit that he only wanted to give interviews with the press anonymously, while Basquiat would have preferred to reveal the duo's identity. Consequently, as of that time, the tag was still briefly used only by Basquiat, who, instead of the usual philosophical phrases, wrote only, "SAMO is dead."

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli