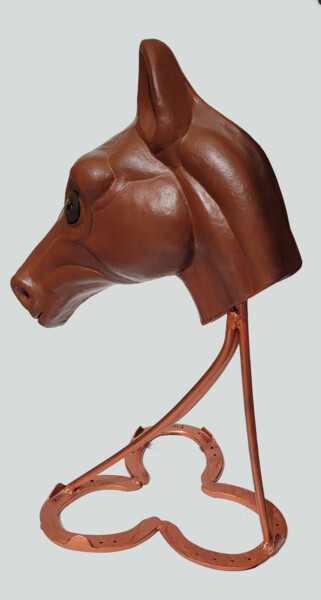

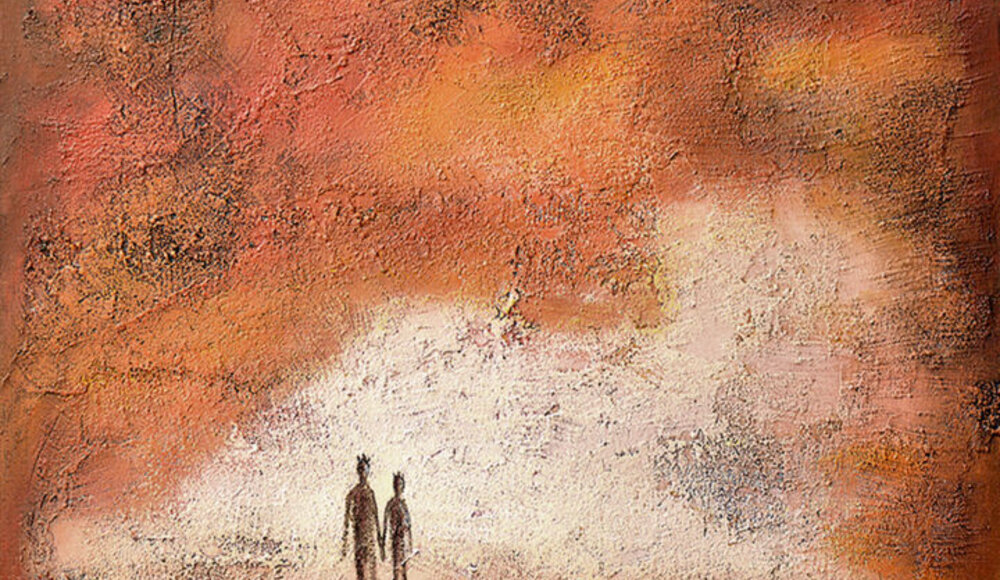

Picrate, The big night, 2022. Acrylic / pigments on linen canvas.

Picrate, The big night, 2022. Acrylic / pigments on linen canvas.

Georges Braques and the brown

"It starts out looking like it has nothing to say, but then brown always ends up making love to chestnuts and autumn."

The words of Fabrizio Caramagna, the Italian "wonder-seeker" born in 1969 and specializing in the creation of successful aphorisms, powerfully synthesize the inability of first impressions to capture the full potential of things and people, as well as summarizing the close connection between the color brown and the autumn reality, well exemplified precisely by the dusk of falling leaves. It is precisely this latter association that often makes the aforementioned nuance appear limited to a specific context, as well as monotonous and unglamorous, compared to the other colors in the color circle. In reality, brown has demonstrated its relevance over the centuries in the artistic sphere, an area in which it has been used predominantly to bring to life crepuscular or dark tones, as well as for the creation, through the shades of burnt sienna and burnt umber, of subtle gradations of chiaroscuro. In other contexts, such a combination of red and green became the protagonist of some masterpieces of art history, within which it shaped the main subjects of the canvas, as, for example, George Braque's Man with a Guitar (1912). The pictorial surface of the latter painting, literally dissected into chiaroscuro fragments, houses at its center the key holding the guitar string, while the presence of the male figure, difficult to identify, is possible to imagine only by referring to the work's title. In fact, Man with a Guitar requires a considerable effort of interpretation, as the viewer has to abandon the search for references to the known world, in order to be led by the mechanisms of reason, aimed at reconstructing a new and unprecedented contemplative dimension. About the use of color, on the other hand, the work re-proposes a chromaticism dear to the French Cubist, who, starting in 1907, that is, during the phase of Primitive Cubism, subjected the images to a process of drastic simplification, aimed at reducing the palette to only shades of green and brown, a process well expressed by the masterpiece Case a L'Estaque (1908). Later, and more precisely during the period of Analytical Cubism (1909-1922), the French master devoted himself to the production of a variety of still lifes, in which the objects, which appear as if reassembled after dismemberment, are made with an equal prevalence of brown, green and gray tones, such as, for example, those in: Violin and Palette (1909), Piano and Mandola (1909-10) and The Clarinet (1912). This type of artistic investigation follows in the works of Synthetic Cubism, enriched by the presence of numbers and letters that are arranged around the figures, in order to "feed" the aesthetic narrative with recognizable figurative elements, pursuing the clear intention of distancing oneself from the movement of abstractionism. Finally, it is good to highlight how such recurrence of brown can also be found in Picasso's cubist work, so much so that it is possible to compare two related paintings made by the aforementioned masters, such as Ma Jolie (1911-12) and The Portuguese (1911-12). Precisely in this context, it emerges, once again, how the prevalence of brown and gray was again used with the purpose of breaking down and fragmenting the reality around us, through skillful chiaroscuro, aimed at generating images too complex to be interpreted through the mere use of sight.

Ilya Volykhine, Kaituhi - writer's block lll, 2022. Oil on canvas, 140 x 120 cm.

Ilya Volykhine, Kaituhi - writer's block lll, 2022. Oil on canvas, 140 x 120 cm.

Luis Guinea (Luison), Dna portrait. Ana Zubizarreta, 2002. oil on canvas.

Luis Guinea (Luison), Dna portrait. Ana Zubizarreta, 2002. oil on canvas.

Brown in art: from prehistory to today

The presence of brown within the history of art boasts a very ancient tradition; in fact, umber, a natural clay pigment composed of iron oxide and manganese oxide, with which the aforementioned color was obtained, was used, both in prehistoric times, that is, in paintings dated 40,000 B.C., and in Upper Paleolithic art, well exemplified by the walls of the Lascaux cave, dating back some 17,300 years. The popularity of the autumn color followed in ancient Egypt, where female figures in funerary paintings were often executed with a skin tone achieved through the use of shadow earth. Such a "tanned" complexion was also successful in the Greek and Roman worlds, where a subtle reddish-brown tint was produced that, made with the ink of a variety of cuttlefish, was later used by the greatest Renaissance masters. In the Medieval period, on the other hand, brown, associated with the humble robes of Franciscan monks, was rarely used in art, as brighter and more regal hues, such as red, blue and green, were preferred. The great comeback of the chestnut color occurred around the 17th century, when the likes of Rembrandt used this hue to create chiaroscuro effects, but also to bring to life a background in which the figures emerged with great prominence. In conclusion, speaking of the 19th and 20th centuries, approaches to the aforementioned hue were different during this period, so much so that brown, hated by the Impressionists, was instead much loved by Gauguin, a painter who created luminous brown portraits of the people and landscapes of Polynesia. Finally, the history of brown continues up to contemporary times, thanks to the original and unprecedented views of Artmajeur artists such as Oleksandr Balbyshev, Radek Smach and Marc Mugnier.

Oleksandr Balbyshev, Melting Lenin, 2016, Oil on canvas, 90 x 70 cm.

Oleksandr Balbyshev, Melting Lenin, 2016, Oil on canvas, 90 x 70 cm.

Oleksandr Balbyshev: Melting Lenin

In Ukrainian painter Balbyshev's painting, Lenin's face appears fragmented, just as if it had been first painted and then, at a later time, erased from the surface of the brown canvas, following impulses and reasons, which seem obscure at first glance. In reality, as made explicit in the artist's own description of Melting Lenin, such a mode of portraying the politician alludes to the impact that Marxist and Leninist ideology had on the Russian art world, turning it into a mere medium of political propaganda, devoid of free evolution. In addition, Balbyshev, in immortalizing Lenin, also wonders how the figurative investigation of the said country might have been if there had not been this period of oppression, a question that, alas, cannot be answered. Speaking of art history, on the other hand, it is known how even Rembrandt used to use brown color as the background of his paintings, in fact, the spreading of a few coats of Bologna chalk and smoothed animal glue, received a layer of white lead in linseed oil mixed with black, shadowy earth or burnt sienna.

Radek Smach, Brown abstract painting va766, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 80 cm.

Radek Smach, Brown abstract painting va766, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 80 cm.

Radek Smach: Brown abstract painting

Brown abstract painting brings back an iconic chromaticism from art history, as the work was made with shades akin to those in Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), a painting by Jackson Pollock dated 1950. In this "modern version" of the mid-twentieth-century masterpiece, the principle of dripping technique is dispensed with, as the colors are regularly, and studiously, spread over the paint medium, rather than "randomly" superimposed by "messy" drips. Despite these differences, the imposition of shades of brown bring to mind, in both works, the atmospheres of autumn, which, in Pollock's case, are explicitly mentioned by the very title of the work. In particular, Autumn Rhythm evokes that season through the energetic movement triggered by the combination of lines and drops of color, aimed almost at claiming the vitality of a time of year often associated only with hibernation or sweet sleep. In the Artmajer artist's work, on the other hand, the studied composition hints at a more traditional autumn, that is, earthy, cozy and routine, marked by an atmosphere that urges introspection, recollection, self-care and protection, aimed at transforming the individual and making him or her "bloom" only in the coming spring.

Marc Mugnier, Wooden spheroid, 2020. Wood sculpture, 40 x 40 x 40 cm.

Marc Mugnier, Wooden spheroid, 2020. Wood sculpture, 40 x 40 x 40 cm.

Marc Mugnier: Wooden spheroid

Mugnier's spherical sculpture was created by assembling pieces of waxed oak, pursuing the goal of revealing some of the mysteries of the nature that surrounds us. In fact, precisely through the use of organic substances, the artist, who, creates a connection with the most authentic matter, wants to transmit the memory of our planet, accompanying it with a strong message of peace and respect for the world in which we live. On the other hand, with regard to the relationship that the viewer should have with Wooden Spheroid, Mugnier is keen to point out that, apart from the message in support of nature, there are no other intentions in his work than to stimulate the free interpretation of the viewer. Finally, from an art-historical point of view, the Artmajeur artist's work is reminiscent of Ben Butler's sculptures, built through the assembly of hundreds of pieces of wood, which, arranged in strange formations, do not follow a definite plan, other than to imitate natural formations.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli