Vincent Monluc, Street vendor in old Hanoi, 2018. Watercolour on Paper, 56 x 37 cm.

Vincent Monluc, Street vendor in old Hanoi, 2018. Watercolour on Paper, 56 x 37 cm.

Yoko Ono, Cut Piece, 1964.

Jumping rich centuries of history and tradition, we come at once to externalize the viewpoint of one of the most celebrated artists of the Vietnamese twentieth century, namely Nguyen Phan Chanh, a pioneer of silk painting within his nation's artistic investigation, who, despite his training at the Ecole des Beaux-arts d'Indochine an institution founded at the time in French Indochina, aimed, according to Western taste, at "transforming indigenous artisans into professional artists," managed to maintain a marked focus on a rather old-fashioned and traditional depiction of village life. The above appears forcefully in his works aimed at portraying characters intent on work, dialogue and leisure with a "realism" akin to the older Chinese tradition, which so influenced Vietnam's "primordial" figurative point of view. Taking a concrete example, I invite the viewer to observe the routine scene captured by After duty hours, a work that, made by the aforementioned master around 1967, that is, at the height of the Vietnam War, astonishes for its serenity, although, in reality, behind the tranquility of the subject matter, lies a passionate patriotic message, aimed at celebrating, as in most of the artist's work, the more traditional modesty and simplicity of the country's rural life. This identity "vindication" can be compared with Western art of the same historical period, aimed at explicating, without any delay, but through a sharp and angry a cry of dissent, all the aversion felt by the artists toward the aforementioned war conflict, which from 1955 to 1975 saw Vietnam pitted against the American superpower. Analyzing some of these political externals expressed through creativity, purely following a chronological order, we start by finding ourselves "face to face" with a young Yoko Ono, grappling with one of her first performance works, Cut Piece, an act within which the artist sat alone on a stage, on which, elegantly dressed, she held in her hands a pair of scissors, in order to invite the audience to approach her and cut off a small piece of her suit, and then jealously preserve and guard it. This performance, in which the viewer takes an active role as opposed to Ono's passivity, has been interpreted not only as an original protest against the Vietnam War, but also as a feminist work, explicitly declared against all sorts of violence and discrimination.

Duy Tran, Landscape of Vietnam, 2022. Oil on Linen Canvas, 60 x 46 cm.

Duy Tran, Landscape of Vietnam, 2022. Oil on Linen Canvas, 60 x 46 cm.

Chris Burden, Shoot, 1971.

Between 1967 and 1972, on the other hand, lies the dating of Red Stripe Kitchen, a work from the series "house Beautiful: Bringing the War Home," which, created by the American artist, photographer and art critic Martha Rosler, pursued the aim of fixing in an image an extremely innovative concept, derived from the new popularity, found at the time, of the television medium, which, for the first time in history, brought the conflict, and its violence, directly into the homes of American citizens, so much so that it was renamed as a sort of "living room war." In reality, however, the photomontage, which places the soldiers inside a quiet interior, was cleverly designed by the artist also in order to achieve the disturbance of a reassuring illusion: the distance between the "here" and the "there," which, inexorably lost, immerses the viewer in an unstable and dangerous situation, having its origins in American foreign policy, as well as in the extreme nature of the culture of consumerism. Finally, we come to the most violent interpretation of the conflict, and thus, arguably, most faithful to the actual fact of the war, which is offered to us by the extreme point of view of U.S. artist Chris Burden, revealed in the 1971 performance entitled Shoot. Precisely, it was November 19 of that same year, when, inside the F-Space gallery in Santa Ana (California, USA), the artist positioned himself in front of his friend, to whom, he addressed the fateful words, "Are you ready Bruce?" An instant later, the .22-caliber rifle wielded by the latter simulated death in a split second, leaving the mark of a gunshot hole in Burden's arm, which, in reality, he should have only grazed. Such an anxiogenic, uncontrollable and violent performance was considered one of the most spectacular of the 1970s, to be set back in an American context extremely overburdened by the fantasies and fears aroused by shootings and gunshot wounds, of which the Vietnam War seemed the most logical and tragic sequel.

Gilles Mével, Diptych: Ha Long Bay. Vietnam. Acrylic on Canvas, 80 x 160 cm.

Gilles Mével, Diptych: Ha Long Bay. Vietnam. Acrylic on Canvas, 80 x 160 cm.

Brief history of the art of Vietnam

In addition to Vietnam's rather turbulent war-historical events, of which the facts mentioned above would represent only a "small portion," without even considering the problems due to colonization and globalization, it is possible to speak, on the other hand, of a solid figurative culture, which, over the centuries, has managed to achieve the attainment of its most authentic identity, aimed at encompassing origins ranging from the Stone Age to the present day. Beginning with 8000 B.C., the production of ceramic objects was extensive in this era, which, starting from the Neolithic period, began to be implemented with fine decorative elements, depicting geometric patterns, scenes of daily life or hunting. Subsequently, Vietnam's creative impulse was drastically affected by China, due, both to the presence of Chinese rulers and actual invasions and seizures of power by "Beijing." If the Chinese influence determined the golden age of Vietnamese artistic production, predominantly realized through a rich production of ceramics, the later French colonization, manifested through the establishment of the École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de l'Indochine, brought, with an intensity never seen before, European methods to Vietnam. After the American interventions of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, one has to wait until the 1990s to speak of a new and flourishing Vietnamese artistic impetus, capable of uniting the traditions of two opposing, complementary worlds inexorably united by history: the West and the East.

Phuong.C Nguyen, Nail time, 2018. Painting, lacquer / pigments / wood on Wood, 75 x 60 cm.

Phuong.C Nguyen, Nail time, 2018. Painting, lacquer / pigments / wood on Wood, 75 x 60 cm.

Phuong.C Nguyen: Nail time

When I first looked at Nail time, I thought I was confronted with a 'classic' work of Thai art, which, marked by red colours, traditional clothes and immersed in the nature of everyday gestures, had the flavour of the point of view of well-known artists such as, for instance, Nguyen Gia Trí and Lê Quốc Lộc. There is, however, one small detail that shifts the dating of the aforementioned painting from circa 19th century styles to the present day: the industrially produced enamel bottle, precisely derived from the studies of the Cutex brand, which, in 1911, devised the first liquid enamel formula. Apart from this anagraphic minutiae, however, the work, which as the artist confides to us was executed during his training period and immortalises his cat, does indeed take up the ancient Thai lacquer technique used by the aforementioned popular masters. In fact, it is possible to think of Nail time as a fragment of Nguyen Gia Trí's Women in the Garden, a work in which not one, but as many as eleven maidens, perform routine activities within a flamboyant, or probably autumnal, landscape. This masterpiece, in which the women appear in all their grace, charm and coquetry, revealed by the sinuosity and flexibility of their bodies, almost makes us forget the complexity of the lacquer painting process, known as Sơn mài, which is a very laborious painting process, which involves the application of several layers of coloured and transparent lacquer, which, after being laid on top of each other and drying, must be rubbed down with sandpaper, charcoal powder and human hair in order to achieve the desired colour. Finally, it is important to specify how the lacquer in question is extracted from the cây sơn tree, a life form that inhabits the mountains of Phú Thọ province.

Gilles Mével, Reflets: Vietnam, 2006. Painting, acrylic on canvas, 100 x 80 cm.

Gilles Mével, Reflets: Vietnam, 2006. Painting, acrylic on canvas, 100 x 80 cm.

Gilles Mével: Reflets, Vietnam

Of Mével's painting, we know the dating and technique, we identify the subject that is manifested through figurativism, but we ignore the precise location in which it comes to life and form, enhancing the theme of the double, which is quadrupled by the presence of water reflections from a typical Vietnamese rice paddy field. To satisfy my and your curiosity, I did some online research, searching the sites of well-known travel agencies, in order to come to a hypothetical conclusion: probably, Vietnam was set in the Mu Cang Chai region, the northern area of the country in question, which is considered one of the most important granaries in the country, as it is home to some of the largest and most picturesque terraced rice fields in all of Asia. In this destination, most mass tourism comes to Sapa, which, located near the border with China, enjoys spectacular, tranquil and authentic landscapes. Speaking of art history instead, the color palette used by the artist in Artmajeur immediately made me think of Sai Son Landscape (1970) by Nguyen Tien Chung (1914 - 1976), a Vietnamese painter who won the Ho Chi Minh Prize for Literature - Art in 2000. Just like the subjects of Vietnam, many of Nguyen Tien Chung's masterpieces depict peasants and workers extremely imbued with national identity, yet revealing to us a stark difference: in the case of Sai Son Landscape, a Vietnamese man looks at the clichés of his country, while, in the case of the Artmajeur artist's work, the point of view in question comes from France.

Vincent Villars, Vietnamese landscape, 2001. Oil on canvas, 85 x 105 cm.

Vincent Villars, Vietnamese landscape, 2001. Oil on canvas, 85 x 105 cm.

Vincent Villars: Vietnamese Landscape

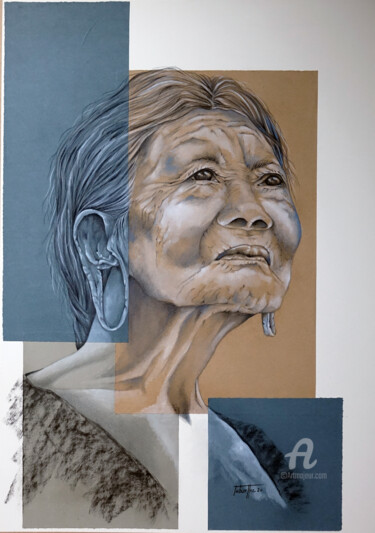

What would have happened if Matisse and Gauguin had visited Vietnam? Villars' Vietnamese landscape answers this question in a hypothetical, original and far-fetched way. It aims to place a traditional character in a red "analogous" to The Dessert: Harmony in Red (1908), a colour scheme within which he assumes the reclining poses of Tahitian Women on the Beach (1891), bringing us back to the example of the École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de l'Indochine and, consequently, to that wind of Western art influences that blew, even later, on the Vietnamese figurative tradition. In fact, at this point, two Vietnamese masters come to mind, whose views were probably influenced, in some of their artistic manifestations, by the figurative production of the 20th century avant-garde, namely: Hoàng Hồng Cẩm and Công Quốc Hà. The former of the two, born in 1959, was a painter who manifested affinities with the current of expressionism, especially when he devoted himself to the depiction of faces in the foreground, while, with regard to broader perspectives, he often complemented the above with purely abstract insights. Regarding Công Quốc Hà, on the other hand, the master, born in 1955, is one of the best-known lacquer painters, who, with his unique and innovative point of view, has breathed new life into traditional Vietnamese art, sometimes presenting affinities with the views of 'naive' art.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli