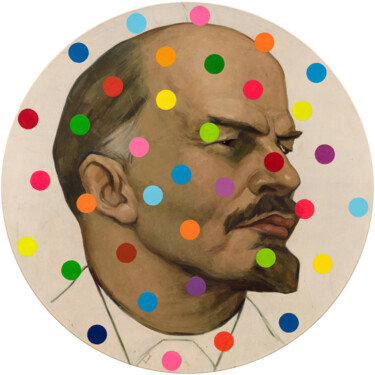

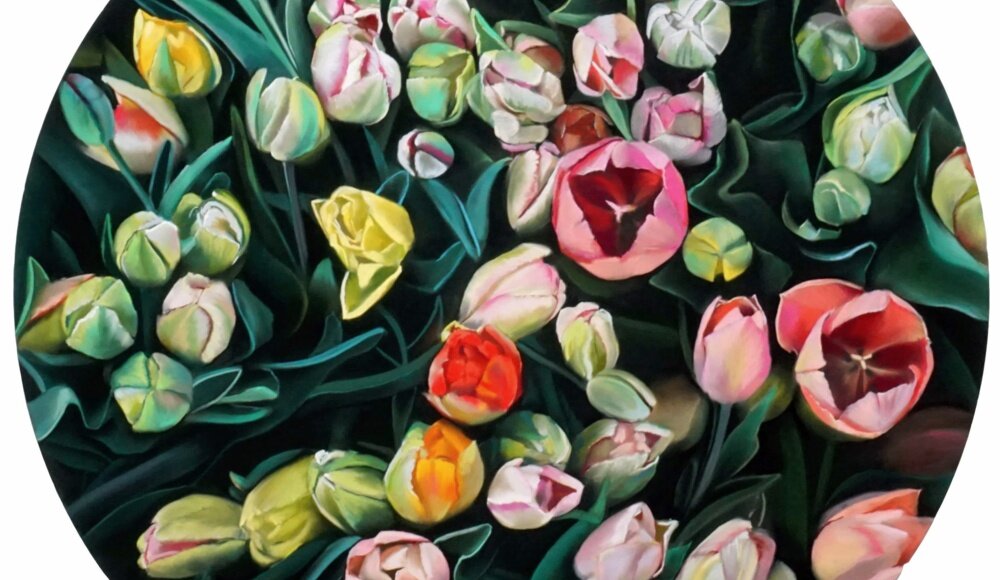

"TULIP CARPET" (2020)Painting by Oxana Babkina.

"TULIP CARPET" (2020)Painting by Oxana Babkina.

Certainly, within the immense breadth of the narrative of art history, works of rectangular or square format stand out in popularity and recurrence, which have often overshadowed the less common round or, even other shaped media. In fact, there is a time when circular supports, called "tondi" (the italian word for round), enjoyed a particular fortune, I am talking about the Renaissance era, a period when, referring to the imago clipeata of ancient Rome, the circle returned to being a popular figure, as well as an undisputed symbol linked to the idea of perfection. In order to demonstrate to you what has been said, it will suffice for me to refer to the round masterpieces kept within a single Italian city: Florence, the Tuscan capital in which the Renaissance dream began and never ended, because even today the city lives on the indelible luster of a time that was, constantly reminded by its solemn buildings and monuments, often collected in the city's most important institutions. Precisely with regard to the latter, I want to start this story, which will take us on a tour of the greatest masters of the time, from the Uffizi Gallery, one of the most important museums in the world, which holds one very well-known tondo in the history of art, namely Michelangelo's Holy Family (1504-06), a tempera on panel painting aimed at depicting the three sacred figures who symbolized par excellence the right family model: St. Joseph, the infant Jesus and the Madonna. Such figures, caught in a moment of serene family life, represented a highly popular subject of Renaissance culture, which underwent multiple variations, as, in this case, it was "associated" with the image of some naked young people, who, placed in the background of the panel, interact with each other under a small portion of the sky. In addition to what we see, the aforementioned masterpiece, also known as the Tondo Doni, tells us of other anecdotes from a bygone era, as it was conceived in the period in which the Florentine co-presence of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael materialized, artists who brought a burst of growth to the already lively environment of the capital, which in the first decade of the century experienced a season of the highest cultural fervor.

Michelangelo, Tondo Doni, c. 1506. Tempera on panel, 120 x 120 cm. Florence: Uffizi.

Just ahead of Michelangelo's aforementioned masterpiece is Botticelli's Madonna of the Magnificat (1483-85), a tempera on panel painted on a round support, also preserved in the Uffizi, whose title derives from the same word that the Child Jesus points to on the open page of a book, where part of the canticle written in Luke's Gospel appears, in a clearly legible way, whose first sentence reads precisely "Magnificat anima mea Dominum" (My soul magnifies the Lord). That scene, in which the Virgin crowned by angels also appears, takes place in front of a window, which, as if to divide the heavenly realm from the earthly world, opens onto a clear country landscape. Finally, speaking of a small detail worth noting, the grains of the pomegranate in the masterpiece, brushed by the fingers of the main protagonists, recall the blood shed by Jesus for human salvation. Turning instead to another, more joyful moment in the life of Christ, it is imperative to consider the last Uffizi work in this review, namely the Adoration of the Magi Tornabuoni (1487), a tondo by Domenico Ghirlandaio in which, keeping in mind the example of Botticelli and Leonardo, the artist created a composition in which the characters, who are placed behind the Holy Family, leave an empty space at the ideal center of the scene, within which the group of the Madonna and Child is set in a pyramidal pattern. Further meanings of the work can be traced to the architectural subjects of its background, within which the shed has been carved out of a large and ancient ruined portico, a tacit symbol of the decline of the pagan religion from which Christianity was born. After the sacred families par excellence, we can move on to a decidedly profane, but nonetheless high-level lineage, as the generator of two inescapable tondi in the history of art, traceable to the work of Filippo Lippi and his son Filippino, the creators of the Tondo Bartoli (1452-53) and the Tondo Corsini (1481-82).

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Adoration of the Magi Tornabuoni, 1487. Tempera on panel, diameter 172. Florence: Uffizi.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Adoration of the Magi Tornabuoni, 1487. Tempera on panel, diameter 172. Florence: Uffizi.

Regarding the former, the work, preserved at the Palatina Gallery in Florence, represents one of the earliest Renaissance tondi, which was probably the "model" for the aforementioned Botticelli masterpiece, as well as the work of other well-known artists of the latter 15th century. In particular, how do I and think that the master of The Birth of Venus took his cues from Lippi? Easy! Just refer to the small but significant detail of the pomegranate, from which, in the case of the 1452-53 work, the Child has extracted a grain to show it to his mother, a gesture to be interpreted as a clear allusion to the Virgin's fertility and royalty. Finally, other scenes related to the life of Mary were painted in the background of Lippi's work, notably the Meeting at the Golden Gate of Joachim and Anne and The Birth of the Virgin. Going from father to son, we conclude our "circular" narrative by arriving at the figure of Filippino Lippi, author of the greatest tondo of the Italian Renaissance: The Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Angels, otherwise known as the Tondo Corsini, a painting at the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze certainly noteworthy for the innovative way in which the architecture and the floor do not go along with the shape of the support, aimed at also accommodating a shaded background, to be recognized as one of the first testimonies of the impact of Leonardo's painting in a painting of the period. Finally, it is good to keep in mind how the success of the roundels within art history, although presenting ups and downs, has lasted until the present day, just as can be seen in the works of some of Artmajeur's artists, such as, for example, Valérie Depadova, Laetitia De Meyer, and Margarita Ivanova.

ROSE - 635 (2022) Painting by Aykaz Arzumanyan.

ROSE - 635 (2022) Painting by Aykaz Arzumanyan.

RESTING WITH FLOWERS (2022)Painting by Valérie Depadova.

RESTING WITH FLOWERS (2022)Painting by Valérie Depadova.

Valérie Depadova: Resting with Flowers

Unfortunately, as in the case of the egg and the hen, we do not know whether for Depadova's painting the round or the depicted subject was born first, that is, whether the artist envisioned a sleeping woman to be gathered within a circular support, or whether the latter made her think of an effigy gently gathered upon herself. What seems most certain, however, is the "childlike" style of the painting, which immediately brings to mind the stylistic features of naïve art, an artistic production decidedly marked by a remarkable conceptual simplification, as well as a "modest" executive technique, which, aimed at "ignoring" the overall perspective and compositional framework, eschews any connection with the cultural and academic reality of the society in which it is produced. At this point a question arises: to which popular naïf artist is it possible to "juxtapose" the work of the aforementioned Artmajeur painter? Certainly the theme of sleep unites The Rest with Flowers with Henri Rousseau's The Sleeping Gypsy (1897), a masterpiece that immortalizes, in its foreground, a woman dressed in a long, colorful dress, intent on sleeping serenely while holding a stick, which rests one of its ends on a desert land. Within the latter arid setting, in addition to several objects, we glimpse the figure of a lion, intent, probably, on watching over the gypsy woman's rest. Similarly, some floating flowers approach the "silhouette" of the protagonist of Depadova's painting, probably lulling the effigy's sweet sleep with their scent.

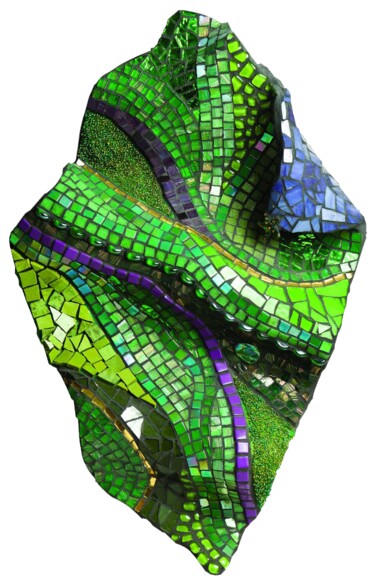

"WONDERLAND II" (2023) Sculpture by Laetitia De Meyer (LDM).

"WONDERLAND II" (2023) Sculpture by Laetitia De Meyer (LDM).

Laetitia De Meyer: Wonderland II

Do you remember the colorful cereals you greedily ate as a child, tossing them in large numbers on an expanse of milk, in which they piled up floating and swaying sinuously? Lo and behold, the multitude of chubby S-shapes, cleverly arranged on the round stand of Wonderland II, made me think of the aerial vision of the filled cup I had as a child, awakening in me, at the same time, a great awareness. In fact, if we refer to the artist's words, De Meyer's sculpture represents not only a cheerful round and colorful work, as it was conceived as a clear warning of the excessive consumption of plastic on our planet, which, progressively invaded by the latter, will probably be deprived of its most succulent dishes, forcing us to feed on the material of consumerism par excellence. At this point I bring up the rhetorical question of Artmajeur's artist, who after this sad revelation reiterates the point by wondering, and asking the viewer, if life in plastic is really that great? Imagining ourselves substituting less tasty dishes for cereal, we surely answer no, although the work's somewhat optimistic colors give us hope that the human fairy tale always has a happy ending, offering our kind future rainbow visions, similar to those captured by John Constable, Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt.

Margarita Ivanova: Circle birch

Referring to Ivanova's words, Circle birch, part of a series of works inspired by the bark of the birch tree, juxtaposes the latter plant with the human life cycle, marked by the endless chain in which the multiple existences, which, so vast in their numbers, are not possible to know in their beginning and end, succeed one after the other. Therefore, I believe that, even if in the smallest way, humankind can be likened to an almost eternal cycle of portraits, aimed at depicting the connotations of the earth's inhabitants in their diversity, which can be summarized, in a very small way, in the tondi depicting some well-known representatives of humankind: the four Evangelists, skillfully immortalized by Pontormo and Bronzino in the Capponi Chapel of the church of Santa Felicita in Florence. Concerning the latter oil on panel paintings, datable to about 1525, they were commissioned by Ludovico Capponi from Pontormo, although Vasari recalls the intervention in the cycle of the master's pupil, namely Bronzino, so much so that today it is only certain the attribution of St. John to the former and St. Matthew to the latter, while on the other two masterpieces hovers the "mystery" of the author. In any case, despite the slight stylistic differences, the tondi are clearly part of a unified program, having as their subject half-length figures in unusual and refined poses, which, often leaning forward, also represent undeniable Michelangelo debts.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli