Following our analysis of Artistic References in TV Shows and Artistic Tributes in Movies, we continue to explore the close links between Art and Pop Culture: this time, we rediscover our classics through comics : let's wet our fingers and turn the page, here we go !

1. Art and Comics

This article is supposed to be contemplative. But before anything else, we can't let you discover these references without some context. That's why, in this introduction, we'll try (as best we can) to dissect nuances and differences between what we consider as "great" art and comics.

At first glance, the ultimate distinctions between what is called "Fine Art" and Comics Art can be found in the accessibility of these two medias. One is considered a luxury product, rare and often expensive, while the other is generally more affordable, produced in large quantities. The similarities, on the other hand, reside in the creative process of the author (a draftsman and a painter work under roughly the same conditions), as well as in the originality and collectability of the final artwork.

The frontier between these two artistic domains remains tenacious, although it has been reduced over time, notably with the emergence of Pop Art in the 1960s.

We can also see a revaluation of works from iconic cartoonists by art institutions such as gallerists, museums and auction houses. Motivated by profit, they respond to a growing demand from comic book lovers, who now have the resources to acquire the frustrating temptations of their childhood.

In 2021, we can legitimately ask ourselves what difference there is between a Mickey comic strip in a book or magazine, and a Mickey comic strip painted on canvas.

Apart from a few changes in color and layout, there's no real distinction between these two artworks. Yet the drawing on the left is available for sale at $50 on Amazon, while Roy Lichtenstein's artwork on the right is valued in some millions, and its rare reproductions are selling for a few thousand.

Andy Warhol, Ten Marilyns, 1963-1967.

Andy Warhol, Ten Marilyns, 1963-1967.

Even if illustrated books have existed for several centuries, the comic book, as we understand it today in Occident, was born at the beginning of the 20th century. At that time, it was obviously very far from the art world. Its creators, its commissioners (newspapers and periodicals) and its public considered this medium to be destined for the masses, as it was easily reproducible thanks to the innovations of printing. For a long time, cartoonists saw themselves more as journalists, columnists or satirists, using their talent with the pencil to convey an idea, a touch of humor or information. In the United States, the triumph of comics began very early, notably with the appearance of the first superhero, Superman, in 1938.

There, it was common (even mechanical) for cartoonists to throw their original panels and sketches directly into Manhattan dumpsters, right after printing. A curious example of the interest these artists had in their drawings: far from underestimating their style, they often had no idea of the value of their work, and didn't really consider themselves artists, but rather producers of drawings and ideas (in a production line), dedicated to the general public.

The post-war period and the beginning of the 60s saw the emergence of the Pop Art trend. Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein appropriated comic book illustrations to create monumental and polished artwork that quickly became very successful. Pulpy and popular mirror of our cultural conscience, these artists recycled the codes of the comic strip to distill a colorful satire of society. Surrounded by collectors, gallerists and merchants, their artwork quickly sold at very high prices, allowing (in spite of themselves) a revaluation of the primary work, the one produced by the cartoonists they themselves copied (or "honored") to realize their Pop Art paintings.

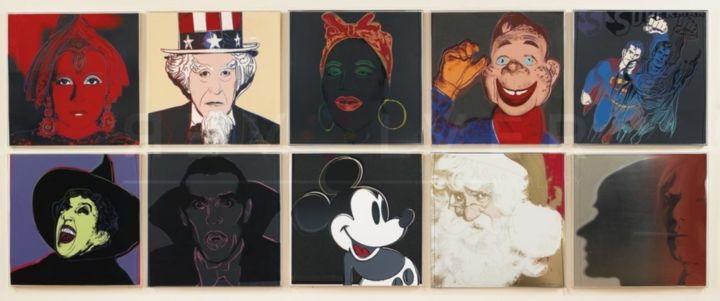

Except for a small number of early fans, few people remember Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the teenagers who created Superman. However, we all know the eccentric and provocative artist Andy Warhol, who used the character of Superman in his "Myths" Series. He's the subject of retrospectives in many museums and his artistic practice is documented by an overabundance of more or less critical writings. A severe difference in treatment between these discreet and forgotten innovators, creators of an empire as imaginary as lucrative, and malicious, triumphant and (somewhat) megalomaniac plagiarists.

Andy Warhol, Myths Series, 1981.

Andy Warhol, Myths Series, 1981.

Despite injustices of the past, the financial gap between comics and fine art is narrowing drastically. Nowadays, it's quite common to see original comics plates at auction in prestigious auction houses. Some of them even reach stratospheric prices, especially when it comes to prestigious licenses such as Superman in the US or Tintin in Europe. As an illustration, in 2021, a drawing by Hergé for the cover of the Tintin album, The Blue Lotus, broke the world auction record for comics, sold for 3.175 million euros including fees (Artcurial). We also find more and more creators who wear the double hat of cartoonists and artists.

For some people, the distinction between contemporary art and comics can be found in the notion of abstraction: where art separates the form and the content (the meaning) of the artwork, comics put the form, the drawing, at the service of the content: it illustrates an idea. Although this analysis is already weakened by centuries of figurative art, it can also be swept away by certain major changes in the comics world. Since the second half of the 20th century, comics have been pushed towards less narrative and more experimental paths. We find, for example, more and more graphic novels where the drawings are at the heart of the story and replace words. Comics, like any form of art, are constantly evolving and overturning the slightest boundaries that are set for them.

Now, it's time to contemplate! To make it easier for you to read, we've decided to structure this (non-exhaustive) list by separating the references to ancient artworks (religious paintings, Renaissance) and tributes to relatively more recent artwork (from 1800 to today). These two distinctions seem necessary because they don't serve the same purpose: ancient references highlight a posture or an idea, while modern references highlight a way of life, a culture, or a simple aesthetic tribute.

2. Ancient references: allegory serving the plot

This first compilation of references will allow us to glimpse how designers appropriate the codes of emblematic masterpieces to quickly spread an idea, by drawing on our unconscious cultural references.

Because if there is a collective consciousness, there is also a collective unconscious. This one is full of figures, images and iconography that we all discern, without sometimes knowing their name.

- The Pietà

Michelangelo, Pietà, 1499. St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City.

Michelangelo, Pietà, 1499. St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City.

Major theme of the religious iconography whose most iconic figure is certainly this sculpture of Michelangelo, the Pietà represents the Virgin Mary crying the death of her son Jesus, with his corpse spread on the knees.

The aesthetics and dramatic postures of this religious theme quickly induce an idea in the reader's brain: that of mourning. The reader can then, consciously or not, identify the plot of a comic book by identifying these ancient postures on the cover of the album. A good tip for cartoonists who want to highlight the death of an important character: there are more than thirty comics with these characteristic features of the Pietà.

- The Last Supper and the Vitruvian Man

Leonardo Da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495-1498. Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan.

Leonardo Da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495-1498. Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan.

Here's another iconic artwork and overabundance in the graphic literature. What is convenient with da Vinci's fresco is that absolutely everyone knows it.

Legion of Super-Heroes #2, Giffen et Levitz - DC Comics

Legion of Super-Heroes #2, Giffen et Levitz - DC Comics

Alice in Wonderland, Gill et Gregory (Couverture de Jason Embury)

Alice in Wonderland, Gill et Gregory (Couverture de Jason Embury)

Besides looking particularly nice to repurpose, the scenography of this artwork allows the designer to emphasize different points: first he can highlight the gathering of different heroes (logical), but he can also present the heroes according to their order of importance, arranging the main protagonists in the center of the table, and then scattering the background characters more in the distance, on the extremities. He can also hint at a potential betrayal, using the figure of Judas.

The Vitruvian Man allows an anatomical representation of the character, particularly interesting for superheroes with special abilities, like Spiderman and his dark version, Venom.

- The Birth of Venus

The use of this powerful artwork by Sandro Botticelli is rarer, but it is recurrent enough to be highlighted. Indeed, it' s mostly used to highlight a story based on a female character. It's no surprise to anyone, comics have long suffered from sexist vices, and there are few female characters as well developed as their Adam's apple counterparts.

Fine arts have also suffered a lot from this systemic misogyny: if you are interested in the subject, we recommend our recent articles (4 Extraordinarily Badass Women Who Changed the Very Patriarchal History of Art, 4 Women Artists Overshadowed by their Husband's Fame) which try to put some parity back in the debate.

3. Modern tributes: symbols of society and culture

In this second compilation, we're going to make a small overview of emblematic artworks: paintings representative of the American culture and society ("American way of life"), but also works representative of the French culture, and some pure aesthetic tributes.

- The American Way of Life

American culture is full of founding myths that symbolize its unity and values. In painting too, symbols abound, with varying degrees of historical veracity. Since the golden age of comic book culture in the early 1940s, many artists have appropriated these paintings to serve their purpose. By compiling the most repurposed artwork, we discover the common core, the iconic masterpieces of American history:

- Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942.

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942.

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942.

Guy Gardner: Warrior #29 - "It's my party and I'll fight if I want to", Beau et Jimenez - DC Comics

Guy Gardner: Warrior #29 - "It's my party and I'll fight if I want to", Beau et Jimenez - DC Comics

Even if Edward Hopper has always refused the label of painter of the American Way of Life, we must admit that his artworks convey a characteristic atmosphere of the urban and lonely America of the mid-20th century. A godsend for artists who can readapt the codes of his emblematic artwork: Nighthawks.

- Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930.

Perhaps even more iconic than Hopper's artwork is American Gothic by painter Grant Wood, which presents rural America in the 1930s.

A symbol that has become a cliché in our time, so many detour have anchored this artwork in the founding myths of America.

- Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, The First Thanksgiving, 1912.

It's hard to get more cliché than this artwork by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, which depicts the first "thanksgiving", mixing a bunch of altruistic settlers with a tribe of docile and greedy Indians, determined to share the turkey together. A (very) idealized representation of the American history, and historically (very) inaccurate.

- Emanuel Leutze, Washington crossing the Delaware, 1851.

- James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Whistler's Mother, 1871.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Whistler's Mother, 1871.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Whistler's Mother, 1871.

- Andrew Wyeth, Christina's World, 1948.

- The emblematic couple-paintings of French culture

In France, too, we see some tasty remakes of cultural symbols of national unity.

Our little French-speaking nugget, Astérix, has given us the pleasure of reinterpreting our main revolutionary myth: La Liberté guidant le Peuple, as well as our dramatic myth, installed next door at the Louvre Museum: The Raft of the Medusa. An ideal readaptation to illustrate the difficulties of the worst pirates in the history of piracy.

- Just for pleasure

Finally, we compile here some unclassifiable references: Sometimes, tributes simply highlight the talent or influence of an artist, and are more an exercise in style than a real interest in the story.

This is notably the case of the "Avengers Art Appreciation" project accompanying the movie release of the Avengers blockbuster in 2012: dozens of illustrators had fun imagining comic book covers inspired by legendary artists and emblematic icons of art history.

Bastien Alleaume (Crapsule Project)

Bastien Alleaume (Crapsule Project)