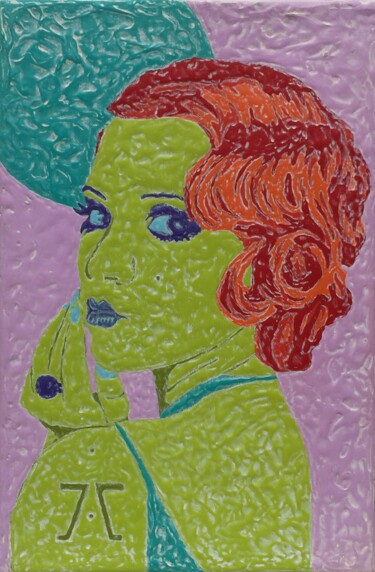

"ANNÉE FOLLE"

On Request

Florence H

"Sirène, esprit des Os"

Acrylic on Canvas | 15.8x15.8 in

$850.58

Prints available