SMOKING VAN GOGH (2019)Fotografia da Mathilde Oscar.

SMOKING VAN GOGH (2019)Fotografia da Mathilde Oscar.

Reverse introduction

"It's really me, but gone crazy." - Van Gogh

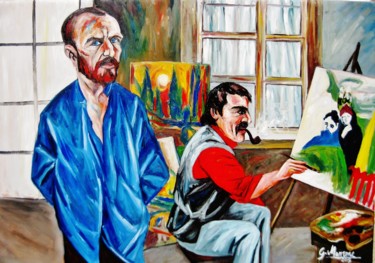

My introduction to the contrary takes the latter meaning in that it aims to omit, only temporarily, both the description of Vincent Van Gogh's multiple self-portraits and the analysis of their historical-artistic, technical, emotional, and stylistic context of belonging, in order to generate a preliminary narrative aimed at presenting the figure of the Dutch artist as it was seen by other great masters of the time, including, John Peter Russell, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Paul Gauguin. In fact, it is precisely the work of the latter that appears to us as a complementary vision, which, to be juxtaposed with Vincent's self-portraits, allows us to understand how, despite the fact that the latter produced masterpieces within which his inner state decisively imposed itself on the real datum, he always remained faithful to the rendering of his most authentic features, even demonstrating that he had the courage to portray himself in the most traumatic moments of his life. Think about it: today, who would put a photo of himself on Instagram depicting him in a moment of full mental breakdown, without flaunting the best version of himself? Only a few life daredevils like Vincent would! Coming back to us, the quotation that opens this art-historical account takes up precisely the words Van Gogh exclaimed when he saw Gauguin's work depicting him, an 1888 image that is undisputedly true of the great postimpressionist, in that it represents a true psychological portrait, where striking details emerge, such as, for example, the half-closed eyes, the deformed head, the low forehead, the face and the crushed nose. It is precisely the latter that have handed down to us the figure of a man tense, fatigued, but devotedly focused on his beloved sunflowers. Finally, parallel to Vincent van Gogh painting sunflowers (1888), the ten Vincent self-portraits I selected offer us the continuation of this figurative narrative "begun" by Gauguin, which will surely be deepened by further introspective and revealing artistic investigation.

Top 10

"It is said-and I am willing to believe it-that it is difficult to know oneself, but neither is it easy to paint oneself." - Van Gogh in a letter to his brother Théo, September 1889.

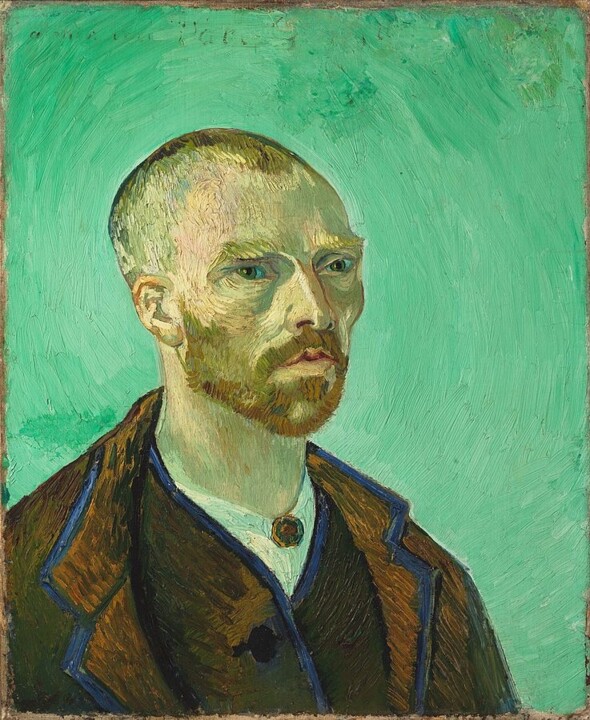

Van Gogh, Self-portrait (dedicated to Paul Gaguin), 1888. Oil on canvas, 61.5 x 50.3 cm. Cambridge: Fogg Art Museum.

Van Gogh, Self-portrait (dedicated to Paul Gaguin), 1888. Oil on canvas, 61.5 x 50.3 cm. Cambridge: Fogg Art Museum.

10. Self-portrait (dedicated to Paul Gaguin) (1888)

Just to carry forward what was made explicit in the introduction, I wanted to quote Vincent's 1889 quote, which, revealing of his serious approach to the genre of the self-portrait, also allows us to imagine the difficulties related to a "four-handed" experimentation with the genre, the result, once again, of one of the most iconic friendship stories in art history: that between Van Gogh and Gauguin. In fact, the self-portrait placed at number ten in my ranking, predating the two artists' dispute, was born at the suggestion of Vincent, who, following the custom of Japanese printmakers to exchange works with each other, suggested to Paul that he make two self-portraits and then, later, do the same. Gauguin, who finished the work first, in addition to portraying himself in the guise of the protagonist of Victor Hugo's novel Les Misérables, accompanied the self-portrait with an affectionate dedication for his friend, who, when he saw the masterpiece arrive, decided to add to his self-portrait the phrase: to my friend Paul Gauguin. Finally, regarding the style of the work, the 1888 painting is definitely inspired by the oriental world, an influence particularly noticeable in the choice of a pale green background, which, without presenting of any shadow, brings out the earthy colors of the effigy.

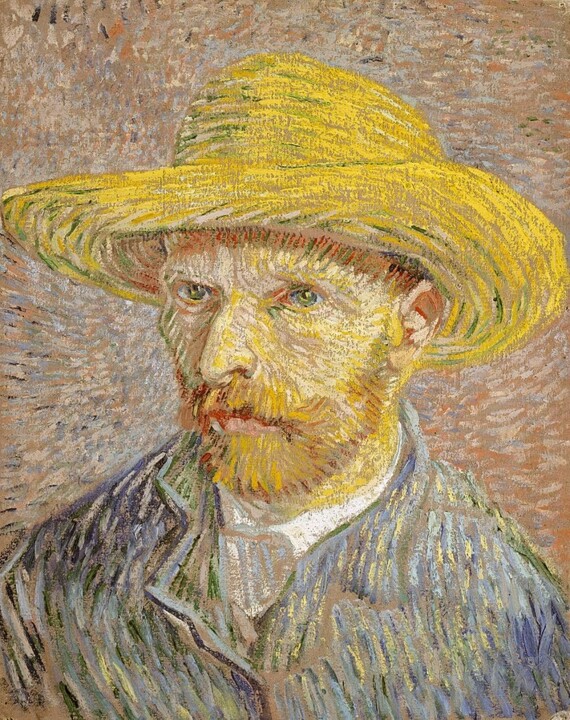

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (obverse: The Potato Peeler), 1887. Oil on canvas, 40.6 x 31.8 cm. New York: MET.

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (obverse: The Potato Peeler), 1887. Oil on canvas, 40.6 x 31.8 cm. New York: MET.

9. Self-Portrait with Straw Hat (1887)

If the self-portrait of 1888 speaks to us of friendship, this one of 1887 represents a real stylistic reflection, since on the back it presents another masterpiece, namely the oil painting of The Potato Peeler, a painting that, dated about 1885 and executed in Nuenen (Netherlands), is a clear example of gloomy and social painting, aimed at immortalizing mainly humble characters portrayed while performing daily actions, narrated through a realism that deforms physiognomies and environments in an expressionistic sense. Van Gogh, who was so poor that he could not buy himself new canvases, painted on the verso of The Potato Peeler, precisely two years later and during his second stay in Paris, the Self-Portrait with Straw Hat, a masterpiece where a remarkably lightened palette is accompanied by sharply visible brushstrokes of different directions and sizes, capable of lending movement and depth to the work. Finally, briefly describing the masterpiece, Vincent appears in the center of the painting frontally and slightly to the left, while his gaze, which is not directed toward the viewer, points in the same direction as his face. Despite this lack of eye-crossing between the effigy and the viewer, Van Gogh's physiognomy appears immediately recognizable, unmistakably marked by a long, sharp nose and eyes of a bright iridescent color.

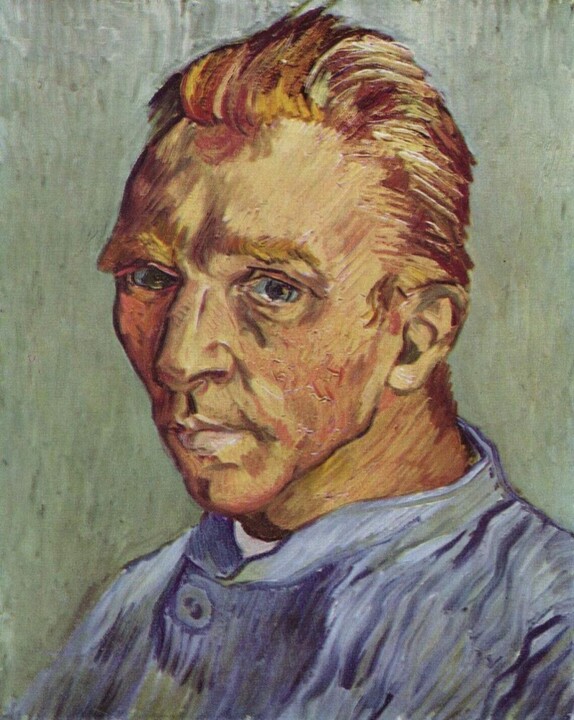

Van Gogh, Self-portrait without beard, 1889. Oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm.

Van Gogh, Self-portrait without beard, 1889. Oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm.

8. Self-portrait without beard (1889)

Many have lingered over the contemplation of Vincent's works without ever having known how he appeared deprived of his iconic reddish beard, therefore, I take this opportunity to demonstrate to you, through the description of the master's Self-Portrait Without a Beard, how Van Gogh, along with many other men of our acquaintance, appears decidedly younger, sometimes almost like a grown boy, after shaving their hirsute faces. Following this physiognomic revelation, I imagine shocking to many, I proceed with the description of the masterpiece, a self-portrait that many have indicated is probably the last one executed by the master, who, he thought fit to give it as a gift to his mother. Probably the artist realized the importance of the bond with the latter by making it stand out after the painful "explosion" of his relationship with Gauguin, an episode that, probably, justifies the melancholy with which this work is charged, becoming a disturbing image, a witness to a life that was beginning to crumble because of the master's mental anxieties. Finally, I report a curiosity: Self-Portrait without Beard is one of the most expensive paintings of all time, so much so that back in 1998 it was in New York for $71.5 million, so much for melancholy!

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait as a Painter, 1887-1888. Oil on canvas, 65.1 × 50 cm. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait as a Painter, 1887-1888. Oil on canvas, 65.1 × 50 cm. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

7. Self-Portrait as a Painter (1888)

How to admire Van Gogh's work without referring to the highest Dutch painting tradition? In fact, a good two hundred and twenty-three years before the aforementioned master, another, of equal fame, painted himself in his role as a painter, I speak of Rembrandt, author, in 1665, of Self-portrait with palette and brushes, a painting that depicts him now in his sixties at work in his studio, a setting in which the presence of some circles, often interpreted as Kabbalistic symbols or stylized globes, is detectable. In the 1888 masterpiece, similarly, Vincent is presented as a painter, who, equipped with palette, brushes and easel, gives proof of being a modern artist, as he is skillfully attentive to the use of bright and complementary colors, clearly distinguishable in shades of red, green, yellow, blue and orange, shades partly present in the same composition of the masterpiece. Finally, I recall other famous self-portraits of painters in their studio, including, Velázquez's Las Meninas, Manet's Self Portrait with a Palette, Courbet's The Painter's Studio, and Jan Vermeer's The Art of Painting.

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Grey Felt Hat, 1887. Oil on cotton, 44.5 cm x 37.2 cm. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

6. Self-Portrait with a Felt Hat (1887)We introduce to Self-Portrait with Felt Hat (1887) by revealing some curiosities about this super-exploited genre by the artist, beginning with the total number of this type of work, of which no less than thirty-five are known! In contrast, only one photograph of Vincent has come down to us, depicting him at the age of nineteen in a truly tough guy, or, to put it better, rather gruff expression. Another important piece of information is about why the artist tried his hand at self-portraiture, a genre exhaustively investigated because the artist, who was penniless and struggling to find models, wanted to practice painting people at all costs. As for the 1887 masterpiece, however, it, made during the master's Parisian period, represents the artist's interest in the pointillist technique, which he clearly applied in his own way, as well as the use of complementary colors, juxtaposed with each other through long brushstrokes in blue, orange, red and green. Precisely unlike the pointillists, Vincent used a distinct type of mark for each area of the canvas, capable of giving rise to a system of lines related to the object or texture depicted.

Van Gogh, Self-portrait with bandaged ear and pipe, 1889. Oil on canvas, 51 × 45 cm. Zurich: Kunsthaus Zürich.

Van Gogh, Self-portrait with bandaged ear and pipe, 1889. Oil on canvas, 51 × 45 cm. Zurich: Kunsthaus Zürich.

5. Self-portrait with bandaged ear and pipe (1889)

This self-portrait represents the effects that a great disappointment, literally the end of a dream, brought to the routine, psyche and physicality of Vincent Van Gogh, who was extremely scarred by the renunciation of starting a common home, as well as a fellowship of art and existence with his friend and painter Paul Gauguin in the well-known yellow house in Arles. In fact, while at first the two had managed to live together in the latter place, soon differences in character drove them apart, culminating in a furious quarrel, which led Vincent, on precisely the date of December 23, 1888, to cut off his left ear and subsequently be hospitalized with a diagnosis of epilepsy, alcoholism and schizophrenia. Precisely one month after this episode of mutilation Van Gogh gave birth to the aforementioned self-portrait, which, as can be seen from the bandaged right ear, instead of the left, was executed by the artist in the mirror, a reflective object on which he is caught in a three-quarter view with a perhaps now resigned expression, which goes well with the more dynamic circles, waves and signs constructed by the smoke of his pipe, having placement on a support where complementary colors were mainly spread.

4. Self-Portrait 1889

To the masterpiece of 1889, which wants Vincent once again portrayed in his role as a painter, we give the task of telling us about the artist's life throughout that year, a period possibly summarized by the master's own words, which he confessed to his dear brother Theo: "I am not really mentally ill, I feel like working and I don't get tired." In fact, after the ear episode, Van Gogh was admitted to the Hotel-Dieu in Arles, to be released on January seven, 1889, a period in which he returned to his beloved yellow house, enjoying the support of Joseph Roulin and his ever-present brother Theo, presences that allowed him to experience moments of serenity in which the master was able to lucidly and ironically assess the surrounding reality, which were sadly accompanied by serious relapses into illness, responsible for another hospitalization as well as the subsequent petition of the citizens of Arles, who wanted him eternally interned. Despite these external pressures it was Vincent who wanted to be hospitalized again, this time at Maison de Santé in Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, an old convent used as a psychiatric hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, a place where Vincent matured a certain awareness: "observing the reality of the life of the insane in this menagerie, I lose the vague terror, the fear of the thing and little by little I can come to consider madness a disease like any other."

Van Gogh, Self-portrait, 1887. Oil on cardboard, 42 × 33.7. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago.

Van Gogh, Self-portrait, 1887. Oil on cardboard, 42 × 33.7. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago.

3. Self-portrait (1887)

On the podium, precisely in third place, is a self-portrait that tells us about Vincent's Parisian sojourn, which, taking place between 1886 and 1888, saw the artist devote himself to the production of at least twenty-four self-portraits, of which, the one that is the object of our attentions stands out to our gaze because of its modest size, its support in board rather than in the recurring canvas, and its thickly dabbed brushstroke, a peculiarity now found in multiple subjects of the same genre and not. Still on the subject of technique, it seems evident how the reference to pointillism actually takes an opposite direction, for if Seurat's method was based on objective and cold science, Van Gogh's was pervaded by the artist's inner world, which in this particular case was manifested in the skillful juxtaposition of particles of green, blue, red and orange, hues intended to give life to a timeless background against which the well-known and emotional effigy stands out. Finally, the languid and profound gaze cast by the masterpiece makes us think of the artist's own statements, who once again revealed to his brother Theo: "I prefer to paint people's eyes to cathedrals...As solemn and imposing as the latter may be, a human soul, be it that of a poor peddler, is more interesting to me."

Van Gogh, Self-portrait with bandaged ear, 1889. Oil on canvas, 60 × 49 cm. London: Courtauld Gallery.

Van Gogh, Self-portrait with bandaged ear, 1889. Oil on canvas, 60 × 49 cm. London: Courtauld Gallery.

2. Self-portrait with bandaged ear (1889)

Since we have already exhaustively discussed Van Gogh's well-known left ear, I would proceed in the presentation of the 1889 masterpiece by dwelling on one detail of it. Starting from a more general description to get to the salient point, in Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear Vincent depicts himself facing to the right, equipped with a heavy dark coat and a furry hat, while his fixed gaze seems to be hallucinated, or perhaps, to put it better, he would seem to be lost in the deep inner sphere of his being. What we are now interested in, however, is the Japanese print that appears to hang on the wall depicted in the background, which has been identified as a work by Sato Torakiyo, reproduced by the Dutch master by shifting the figures and silhouette of Mount Fuji to the right. It is precisely this last oriental masterpiece that leads us to reveal the passion Van Gogh nurtured for Japanese art, so much so that the artist even managed to create his own personal collection of prints, which he was able to collect, as these were at the time on the market at modest prices. Among the various works purchased by the Dutchman, the famous Shin-Ōhashi Bridge in the Rain by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797 - 1858) definitely stands out, a print that is symbolic of an interest that grew in the artist once he arrived in Paris, a city that, mirroring the fashion of the time, offered a large repertoire of oriental prints, including, among others, those that Vincent loved to admire at the gallery of Siegfried Bing (1838 - 1905), a Franco-German merchant who had set up shop on the rue de Provence.

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1889. Oil on canvas, 65 cm × 54 cm: Paris: Musée d'Orsay.

Van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1889. Oil on canvas, 65 cm × 54 cm: Paris: Musée d'Orsay.

1. Self-Portrait (1889)

At number one we find the popular Self-Portrait of 1889, a work through which I dissociate myself from the more general criticism, which, wanting to play the game tell me you're crazy without telling me you are, points to the compulsive ornamentation present in the painting's background as a blatant warning of a latent psychotic state. But what if the artist's obvious mental complexity is simply an aspect to add to his already free and innate creative drive? In the sense, is it possible for a moment to disassociate Vincent from his disorders, perceiving him simply as a healthy carrier of cretivity? Certainly, oftentimes mental illness has fostered the development of artistic talent, but do we want to eclipse the flair gift by talking exclusively about this? Moreover, according to this reasoning all "madmen" should be undisputed geniuses of art! My complex questions certainly cannot be answered by me, although I believe that the "decoration" that the work presents cannot be exhaustively attributed to a delusion, but perhaps, rather, to the strength of the combination of a fragile mind and an extraordinary imagination, characteristics through which Vincent was able to reinvent the genre of portraiture, giving free rein to the innermost, and sometimes impulsive and irrational motions of the human soul, showing them without any shame.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli