Who was Robert Frank?

Robert Frank (1924- 2019), a Swiss photographer and documentary filmmaker, achieved American citizenship and is known for his remarkable contributions to the field. His renowned piece of work, a book called The Americans published in 1958, garnered immense recognition for its fresh and insightful portrayal of American society from an outsider's perspective, earning Frank comparisons to the contemporary French philosopher de Tocqueville. The book revolutionized the realm of photography by redefining its capabilities and expressive potential. In fact, it is widely regarded as the most influential photography book of the 20th century. Following his success in photography, Frank ventured into film and video, where he continued to push boundaries by experimenting with techniques such as manipulating photographs and creating photomontages.

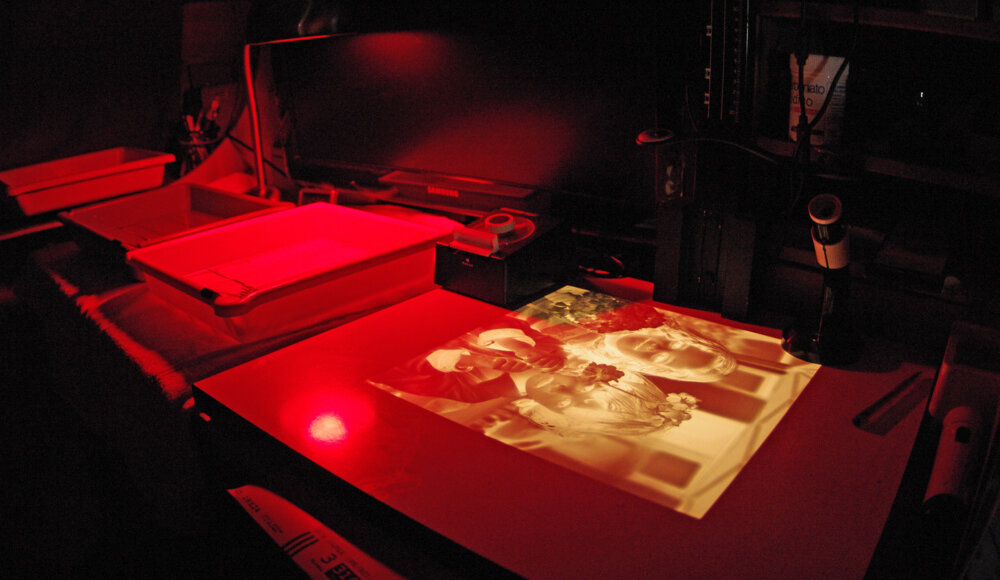

A photographic darkroom with safelight. Photo credits: Inkaroad, via Wikipedia.

A photographic darkroom with safelight. Photo credits: Inkaroad, via Wikipedia.

Historical context and initial experiences in the field of photography

Frank was born into a Jewish family in Zürich, Switzerland. His mother, Rosa (sometimes referred to as Regina), held Swiss citizenship, while his father, Hermann, originally from Frankfurt, Germany, became stateless after losing his German citizenship due to being Jewish. In order to ensure their safety during World War II, Frank and his family applied for Swiss citizenship. Although they remained protected in Switzerland, the looming threat of Nazism deeply influenced Frank's understanding of oppression. Seeking an escape from his family's business-oriented environment, he turned to photography and received training from several photographers and graphic designers. In 1946, he created his first handmade book of photographs titled "40 Fotos."

In 1947, Frank emigrated to the United States and secured a job as a fashion photographer for Harper's Bazaar in New York City. In 1949, his work was featured alongside Jakob Tuggener's photographs in Camera magazine, positioning both artists as representatives of the "new photography" of Switzerland. Tuggener served as a role model for Frank, introduced to him by his mentor, Zurich commercial photographer Michael Wolgensinger. Tuggener's artistic approach, free from commercial constraints, deeply resonated with Frank.

Frank embarked on travels to South America and Europe, creating another handmade book of photographs capturing his experiences in Peru. He returned to the United States in 1950, which proved to be a significant year for him. He met Edward Steichen and participated in the group exhibition "51 American Photographers" at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Additionally, he married Mary Lockspeiser, an artist, with whom he had two children.

Initially, Frank held an optimistic view of American society and culture, but his perspective quickly shifted as he encountered the fast-paced and money-centric nature of American life. He began to see America as a desolate and isolated place, a sentiment that became evident in his later photography. Frank also became dissatisfied with the control exerted by editors over his work. He continued to travel and briefly moved his family to Paris. In 1953, he returned to New York City and worked as a freelance photojournalist for magazines such as McCall's, Vogue, and Fortune. During the 1940s and 1950s, he associated with fellow photographers Saul Leiter and Diane Arbus, contributing to the formation of what Jane Livingston referred to as The New York School of photographers (distinct from the New York School of art).

In 1955, Frank gained further recognition when Edward Steichen included seven of his photographs in the renowned Museum of Modern Art exhibition "The Family of Man." These photographs, taken in Spain, Peru, Wales, England, and the US, resonated with viewers and contributed to the exhibition's success, which was seen by millions of people worldwide.

The Americans

Drawing inspiration from fellow Swiss artist Jakob Tuggener's book Fabrik, Bill Brandt's The English at Home, and Walker Evans's American Photographs, Robert Frank received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1955 from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. This grant enabled him to embark on a journey across the United States, capturing photographs that depicted various layers of American society. His travels took him to cities such as Detroit, Dearborn, Savannah, Miami Beach, St. Petersburg, New Orleans, Houston, Los Angeles, Reno, Salt Lake City, Butte, and Chicago. Accompanied by his family for part of the trip, Frank took a staggering 28,000 shots, from which he selected 83 for publication in his groundbreaking work, The Americans.

During his travels, Frank encountered incidents that shaped his perspective on America. He faced anti-Semitism in a small town in Arkansas, where he was subjected to mistreatment by a policeman and temporarily detained. In other Southern locations, he was given an ultimatum to leave town within an hour. These experiences likely contributed to the somber and critical tone that permeates his work.

Upon his return to New York in 1957, Frank met Beat writer Jack Kerouac, who showed great interest in his photographs from the journey. Kerouac offered to write an introduction for the American edition of The Americans and became one of Frank's lifelong friends. Frank also formed a close bond with Allen Ginsberg, and his documentation of the Beat subculture reflected his exploration of the tensions between the optimistic facade of the 1950s and the underlying class and racial disparities. His unconventional photographic techniques, including unusual focus, low lighting, and unconventional cropping, set his work apart from the mainstream photojournalism of the time.

Initially, Frank faced challenges in finding an American publisher due to his departure from traditional photographic standards. Les Américains was first published in 1958 by Robert Delpire in Paris as part of the Encyclopédie Essentielle series, featuring accompanying texts by renowned writers. The American edition was eventually published in 1959 by Grove Press, receiving mixed reviews initially. However, the endorsement by Kerouac helped increase its exposure and reach a broader audience. Over time, The Americans became a seminal work in American photography and art history, with Frank becoming closely associated with the project. It is considered one of the most influential photography books of the 20th century.

In 1961, Frank had his first solo exhibition titled "Robert Frank: Photographer" at the Art Institute of Chicago, followed by a showing at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1962. He received further recognition through dedicated issues of the French Journal Les Cahiers de la photographie in 1983, showcasing critical discussions on his work as a gesture of admiration.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of The Americans' initial publication, a new edition was released in 2008, featuring uncropped photographs and alternative perspectives for some images. The occasion was marked by a celebratory exhibition titled "Looking In: Robert Frank's The Americans" at the National Gallery of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The exhibition showcased Frank's original Guggenheim Fellowship application, vintage contact sheets, letters exchanged with Walker Evans and Jack Kerouac, and collages assembled under Frank's supervision, providing insight into his creative process. An accompanying book, also titled "Looking In: Robert Frank's The Americans," offered a comprehensive examination of the iconic work. Additionally, a book called "By the Glow of the Jukebox: The Americans List" featured favorite images selected by notable photographers who visited the exhibition at SFMOMA.

A camera obscura used for drawing, via Wikipedia.

A camera obscura used for drawing, via Wikipedia.

Insights:

The Americans (photography)

"The Americans" is a groundbreaking photography book by Robert Frank that had a profound impact on American photography in the post-war era. Originally published in France in 1958 and later in the United States in 1959, the book presented a distinctive perspective by capturing both the upper and lower echelons of American society from a detached viewpoint. The collection of photographs depicted a complex portrait of the time, reflecting skepticism towards prevailing values and conveying a pervasive sense of solitude. Frank's work in "The Americans" was seen as a departure from commercial constraints, showcasing a fresh and rebellious approach akin to the spirit of the Beat Generation.

Background

In 1949, Walter Laubli, the new editor of Camera magazine, published a significant portfolio featuring photographs by Jakob Tuggener and a young Robert Frank. Frank had recently returned to Switzerland after spending two years abroad, and his portion of the magazine showcased some of his earliest pictures from New York. The magazine presented them as representatives of the "new photography" movement in Switzerland.

For Frank, Tuggener served as a role model, introduced to him by his boss and mentor, Michael Wolgensinger, a commercial photographer from Zurich. Wolgensinger believed that Frank would not fit into the commercial photography system, and he recommended Tuggener as an artist whom Frank truly admired. Tuggener's photo book, "Fabrik," published in 1943, inspired Frank with its poetic sequencing and absence of text, resembling a silent movie. This book later influenced Frank's own work, particularly his renowned publication, "Les Américains," released in 1958 in Paris by Delpire.

Frank's creative vision was also shaped by other sources of inspiration, including Tuggener's book, Bill Brandt's "The English at Home" from 1936, and Walker Evans's "American Photographs" from 1938. These works, along with recommendations from photographers like Edward Steichen and Alexey Brodovitch, led Frank to secure a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1955. The fellowship provided him with the opportunity to travel across the United States for two years, capturing photographs that represented all layers of American society. During this time, he took a staggering 28,000 shots, but only 83 of them were ultimately selected for publication in his iconic work, "The Americans."

Frank's journey through America was not without challenges. While driving through Arkansas, he was unjustly thrown in jail for three days, accused of being a communist based on arbitrary reasons such as his appearance, Jewish heritage, possession of letters with Russian-sounding names, and his foreign-sounding whiskey. In another incident, a sheriff in the South warned Frank that he had only an hour to leave town. These experiences highlight the difficulties and prejudices he faced during his photographic journey.

Introduction, style and critical view

Upon his return to New York in 1957, Robert Frank encountered Beat writer Jack Kerouac on the sidewalk outside a party and shared his travel photographs with him. Kerouac was immediately enthralled and offered to write an introduction for the American edition of Frank's book, "The Americans." Frank's photographs captured a contrast between the glossy image of American culture and wealth and the underlying issues of race and class, diverging from the more conventional approaches of contemporary American photojournalists. His unconventional use of focus, low lighting, and unconventional cropping techniques further set his work apart. However, the initial reception of the book in the United States was harsh, with criticism aimed at both its tone, perceived as derogatory to national ideals, and Frank's photojournalistic style, which introduced technical imperfections. In contrast, Walker Evans's "American Photographs," which directly inspired Frank, featured meticulously framed images captured with large-format view cameras. Despite initially poor sales, Kerouac's introduction helped "The Americans" reach a wider audience due to the popularity of the Beat phenomenon. Over time, the book became a seminal work in American photography and art history, becoming closely associated with Frank's legacy.

Sociologist Howard S. Becker has analyzed "The Americans" as a form of social analysis, drawing parallels between the book and Tocqueville's examination of American institutions, as well as the cultural analysis by Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict. Becker argues that Frank's photographs, taken in various locations across the country, repeatedly explore themes such as the flag, automobiles, race, and restaurants. Through the weight of the associations in which he embeds these artifacts, Frank transforms them into profound and meaningful symbols of American culture.

Undeveloped Arista black-and-white film, ISO 125/22°. Photo credits: Shirimasen, via Wikipedia.

Undeveloped Arista black-and-white film, ISO 125/22°. Photo credits: Shirimasen, via Wikipedia.

Publication history

Frank initially faced challenges in finding an American publisher due to his deviation from conventional photographic standards. The first publication of "Les Américains" took place on May 15, 1958, in Paris as part of the Encyclopédie Essentielle series by Robert Delpire. The book included writings by Simone de Beauvoir, Erskine Caldwell, William Faulkner, Henry Miller, and John Steinbeck, which were juxtaposed with Frank's photographs. Some critics felt that the photos primarily served as illustrations for the writing. The cover featured a drawing by Saul Steinberg.

In 1959, "The Americans" was finally published in the United States by Grove Press. However, the text from the French edition was removed due to concerns that it conveyed a tone too critical of American values. The American edition included an introduction by Kerouac and simple captions for the photos, following the layout style of Walker Evans' "American Photographs."

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the book's original publication, a new edition was released by Steidl in 2008. Frank actively participated in the design and production process, utilizing modern scanning techniques for his original prints and employing tritone printing. The book featured a new format, selected typography, and a redesigned cover. Frank personally made adjustments to the cropping of many photographs, often including additional information, and selected slightly different versions for a couple of images.

Films

After the publication of "The Americans" in 1959, Robert Frank shifted his focus to filmmaking. One of his notable films was "Pull My Daisy" (1959), a collaboration with Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and other figures from the Beat movement. The film was initially praised as an improvisational masterpiece, but it was later revealed that it had been carefully planned and directed by Frank and his co-director, Alfred Leslie.

In 1960, Frank stayed in artist George Segal's basement while working on the film "The Sin of Jesus," which received a grant from Walter K. Gutman. The film, based on Isaac Babel's story, centered around a woman working on a chicken farm in New Jersey. Originally intended to be shot in six weeks, the production ended up spanning six months.

Frank's most well-known documentary film is "Cocksucker Blues" (1972), featuring the Rolling Stones during their tour. The film depicted the band's indulgence in drugs and group sex, capturing both the excitement and the boredom of their fame. Mick Jagger reportedly told Frank that the film was excellent but feared that if it was shown in America, the band would be barred from the country. The Stones sued to prevent its release, and the copyright ownership became a subject of dispute. A court order limited the film to be shown only five times per year, in Frank's presence.

Frank's photography also appeared on the cover of the Rolling Stones' album "Exile on Main St." Some of his other films include "Me and My Brother," "Keep Busy," and "Candy Mountain," the latter of which was co-directed with Rudy Wurlitzer.

Death

In the 1970s, Robert Frank shifted his focus back to still photography after his earlier ventures into film and video. He published his second photographic book, "The Lines of My Hand," in 1972. This work is often described as a visual autobiography and primarily features personal photographs. However, Frank moved away from traditional photography techniques and began creating narratives through constructed images and collages. His later works incorporated words, multiple frames of scratched and distorted images, and unconventional techniques. Despite his experimentation, none of his later works achieved the same impact as his seminal work, "The Americans." Some critics argue that by the time Frank delved into constructed images, it was no longer groundbreaking due to Robert Rauschenberg's introduction of silkscreen composites.

In his personal life, Frank went through a significant transition. He separated from his first wife, Mary, in 1969 and remarried sculptor June Leaf. In 1971, he moved to Mabou, Nova Scotia, in Canada, where he split his time between his coastal home and his loft in New York City. Tragedy struck when his daughter, Andrea, died in a plane crash in Tikal, Guatemala, in 1974. Around the same time, his son, Pablo, was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Frank's subsequent works often explored the profound impact of these personal losses. In memory of his daughter, he established the Andrea Frank Foundation in 1995, which offers grants to artists.

Frank gained a reputation for being reclusive, particularly following the deaths of his daughter and son. He declined numerous interviews and public appearances but continued to accept unique assignments, such as photographing the 1984 Democratic National Convention and directing music videos for artists like New Order and Patti Smith. He continued producing films and still images, organizing retrospectives of his artwork, and his work was represented by the Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York since 1984. In 1994, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., hosted a comprehensive retrospective of Frank's work titled "Moving Out."

Robert Frank passed away on September 9, 2019, at his home in Nova Scotia, leaving behind a significant legacy in the world of photography.

Selena Mattei

Selena Mattei