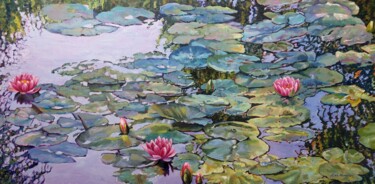

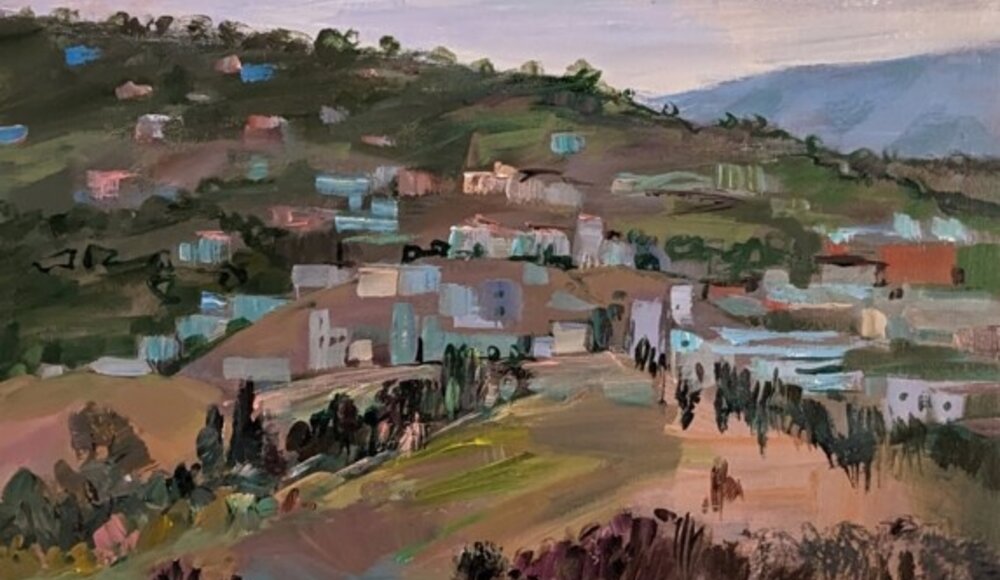

Armen Ghazayran, View from the window, acrylic on cardboard, 50,8 x 40,6 cm.

Armen Ghazayran, View from the window, acrylic on cardboard, 50,8 x 40,6 cm.

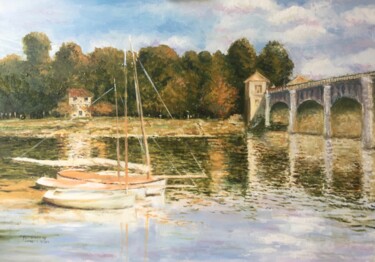

When people talk to us about Impressionism, generally, we are reminded of the image of the "typical" bearded and somewhat "clochard" French painter, who, intent on painting with his hands smeared with color, sheltering under a parasol or a hat, is ready to capture the changing seasons, lights, shadows and colors, times to manifest themselves on the same subject or multiple. Such mental representation, probably vitiated by the very features of Claude Monet, "bo$$" of the artistic current par excellence, lead one to reflect on the fact of how, French Impressionism, imposed itself forcefully in our conception, often "eclipsing" the curiosity of knowing "foreign" interpretations of the same trend. The theme of the depiction of women within the landscape genre seems perfect for comparing the Parisian style with the American, Italian and Spanish styles, i.e., just a few of the multiple points of view that have emerged on the aforementioned current. Starting with the most famous master, Monet's Walk on the Cliff (1882) literally immerses the figure of the woman in nature, a physical world within which, the fusion and chromatic harmony lead to the perception of the human being as an "extension" of the cliff itself. In addition, to the above description are added the typical traits of Monet's female interpretation, who, in masterpieces of the caliber of The Walk (1875) and The Poppies (1873), had already represented women equipped with the "scenic" dresses of the time accompanied by "fluttering" hats and sun umbrella. Such a mode of female representation seems to be "studied," in order to enrich the landscape with delightful figures, who, well-dressed, bring to nature the grace of the most placid and "superficial" femininity, understood as a silent form to be contemplated in its beauty. Returning for a moment to the masterpiece Walk on the Cliff, it is important to recount how, the iconic painting, housed at the Art Institute in Chicago, represents a genuine fruit of the master's sensibility, who created a fresh, immediate, deep and luminous composition, within which three distinct masses can be identified, namely that of the sky of the sea and the cliff, in which he skillfully inserts the figures of the two women, the sails in the sea and the clouds in the sky. A vision of the female gender focused more on an "introspective" and "intimate" interpretation, albeit still delicate and studiously elegant, is instead provided to us by a later work of 1872, which, titled Spring, frames more closely the image of Camille Monet, who, silent and absorbed in reading, is caught in a typically domestic scene, taking place in Argenteuil, a village northwest of Paris to which the painter moved with his family in 1871.

Claude Monet, Walk on the cliff, 1882. Oil on canvas. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago

Claude Monet, Walk on the cliff, 1882. Oil on canvas. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago

John Singer Sargent, The Black Brook, c.1908. Oil paint on canvas. London: Tate.

John Singer Sargent, The Black Brook, c.1908. Oil paint on canvas. London: Tate.

American Impressionism "responded" to Monet by eliminating the book and, as a result, increasing the emotional charge of the effigy, who finds herself "lost" within her own interiority, just as seen in John Singer Sargent's The Black Brook (1908) and Mary Cassat's Portrait of a young girl (1899). Speaking of the first masterpiece, the pensive and lonely subject portrayed by the well-known American painter is the artist's niece, Rose-Marie Ormond, who, at the time, was 15 years old and sat beside a brook in Aosta, a town in northern Italy. It is precisely this naturalistic setting that serves the painter as the second focus of the work, which pursues the intent of capturing the movement of light and shadow on the stream, the flowers, and the girl's dress, through a thick and unelaborate pictorial "stroke." As for Mary Cassat, her "analogous" interpretation of the female figure takes place at or near Château Beaufresne, that is, in the vicinity of the house the artist had purchased in 1894 in the valley of the Oise River, about fifty miles northwest of Paris. Such a view, however, is enriched by an elevated vantage point, which renders the space flattened and without a horizon, features intended to suggest the important influence that Japanese art exerted on the overseas painter. Speaking of Italy, on the other hand, the painting of the Macchiaiolo Giovanni Fattori becomes evidence of how, to the typical parasol parasols and "scenographic" poses in Monet, more intimate and solitary attitudes can be accompanied, aimed at depriving the subject, in part, of its more frivolous femininity. Such an "objective" was pursued by the Tuscan artist in Lady in the Open Air (1866), an oil on panel painting preserved at the Pinacoteca di Brera (Milan), in which the idea of recollection is given to us by the use of a predominantly dark palette, which, tending to brown, envelops the effigy as a sort of melancholic "aura" aimed at bringing silence, solitude and reflection. In addition, the woman's face is darkened by the shadow of the parasol itself, under which, mysteriously, the features of a faceless figure are revealed, that is, without eyes, mouth, nose, etc. Nevertheless, to brighten the woman's thoughts intervenes the providential sun, bright star that gives its best to make the white of the long dress of the table's protagonist shine. Finally, speaking "Spanish," we come to one of the best-known exponents of Impressionism on the Iberian Peninsula, Joaquín Sorolla, who, in Instantánea, Biarritz, a work of 1906, shows great affinities with Monet, having created a typically summer painting, in which the protagonist, dressed in white and depicted in the center of the work, is almost certainly the artist's own wife, Clotilde Garcià del Castillo. The woman, realized with rapid brushstrokes and flicks of color, characterized by a few chromatic touches having the purpose of making the figures, seems to be the distant Spanish cousin of the Camille Monet of The Promenade (1875), a work that Monet made from a different figurative, spatial and luminous framing. The tale of the world's Impressionism continues through the work of Artmajeur artists who interpreted one of the most iconic currents in art, such as Yue Zeng, Xuan Khanh Nguyen and Natalya Savenkova.

Yue Zeng, Landscape study #9 straw bales, 2021. Oil on canvas, 27,9 x 35,6 cm.

Yue Zeng, Landscape study #9 straw bales, 2021. Oil on canvas, 27,9 x 35,6 cm.

Yue Zeng: Landscape study #9 Straw bales

Zeng's oil painting depicts, through multiple and fleeting brush strokes of a purely Impressionist manner, an expansive and sunny wheat field, within which, on the right, the figure of the undisputed protagonist of the work is outlined, namely one of those typical straw bales that, multiple and silent, are arranged on the rural landscapes, conveying to the viewer all the incommunicability inherent in the presence of an inanimate being. Such a description could be partly "recycled" in order to describe one of the undisputed masterpieces of the aforementioned movement, which immortalized a similar subject: haystacks. The work in question, created by Monet, titled Haystacks, End of Summer and dated 1890, is part of a series of paintings in which the French master, as was his wont, dissected the same subject matter by immortalizing it from multiple luminous viewpoints. In this particular case, the artist specifically went to a field not far from Giverny, a location in which he operated during several months, in order to faithfully record the changing weather conditions. Among the many achievements, the one of 1890 stands out for its rendering on the canvas support of a landscape bathed in sunlight, within which the presence of two solitary sheaves of wheat stalks imposes itself, among which, the one on the right, being closer to the viewer, turns out to be much larger than the second, despite the fact that the latter is actually a little further away. Finally, the two dumb clusters of wheat almost seem to be looking romantically at the horizon, on which, in the distance, their presence is replaced by that of trees and hills, overhung by a sky cleared of clouds.

Xuan Khanh Nguyen, Row of red trees #12, 2023. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 50 cm.

Xuan Khanh Nguyen, Row of red trees #12, 2023. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 50 cm.

Xuan Khanh Nguyen: Row of the red trees #12

Frederick Childe Hassam U.S. Impressionist painter born in 1859 created Celia Thaxter's Garden, Isles of Shoals, Maine in 1890, a painting that represents the culmination of his production, which took place during the summers of the late nineteenth century, spent at the location of Appledore Island (New Hampshire), at the sumptuous garden of the poetess Celia Thaxter, a close friend of the artist. The concept behind the success of this work is precisely the color contrast, which the painter has synthesized in the depiction of the red of the flowers and the white of the rocky terrain, which, in the distance, provide a perspective backdrop along with the ocean. The sensations provided by the aforementioned tonal match originate a clear stimulation of the senses, which, ignited by the red and softened by the pastel tones, is intended to reiterate the wild appearance of the flowers, triumphant over the horizontal balance of the quiet background. This description has points in common with Artmajeur Nguyen's artist's painting, whose work, titled Row of the red trees #12, appears to show "overgrown" flowers, which, having become red trees, impose themselves in the composition, capturing the viewer's attention, as they are enhanced by the calmness of the surrounding chromaticism. Adding to this the artist's own words, the "flamboyant" acrylic would pursue the intent of telling the story of the routine of Vietnamese schoolgirls who, dressed according to local tradition, concretize, through art, the narrative of the simplest daily life.

Natalya Savenkova, Italy painting Riomaggiore, 2022. Oil on canvas, 30 x 40 cm.

Natalya Savenkova, Italy painting Riomaggiore, 2022. Oil on canvas, 30 x 40 cm.

Natalya Savenkova: Italy painting Riomaggiore

The skill of a painter is to capture the beauty, or meaningfulness, of the real, carefully scrutinizing with his eyes what surrounds him, in order to "recompose" it into revealing visions, capable of demonstrating to humanity the power of creation. These phrases, with a rather romantic tendency, seem to take on a "minor" value, if one finds oneself in a place of the caliber of Riomaggiore (Liguria, Italy), a tourist destination par excellence in which nature, first, imposed itself as a masterful artist, capable of combining views and colors, worthy of a contemporary Pygmalion who, after creating such a masterpiece, should have fallen in love with it without allowing man to enjoy it. It is precisely in this context that the artist's work appears almost facilitated, as the Cinque Terre offer in all their variations, excellent visual cues ready-made. Within the history of art, an example of "this art within art" is offered to us by the production of the Florentine Macchiaiolo Telemaco Signorini, who, after falling in love with Riomaggiore, settled there in the second half of the 19th century, a period during which he immortalized the village from different points of view and angles, expressing his love for the place through these words: "Among that precipitate of vaults and stairs we descended into the narrow gorge of the port of call, to the marina, and there was the awakening of our senses." Artmajeur artist Savenkova seems to make such a "composition" resonate in her view of Cinque Terre, offering us a perspective that reminds us, in a unique and original way, of the Ligurian landscapes of the Tuscan master.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli