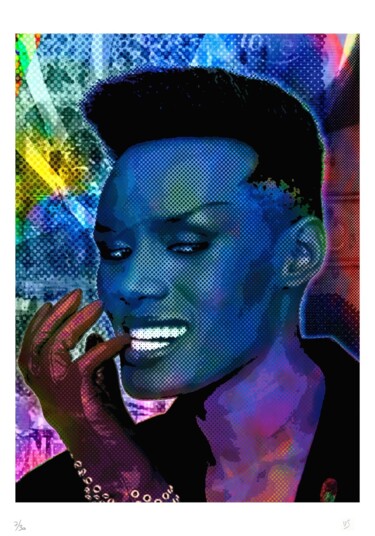

LADY GAGA (2022)Digital Arts by Sobalvarro.

LADY GAGA (2022)Digital Arts by Sobalvarro.

Katy Perry, Beyonce and Lady Gaga...

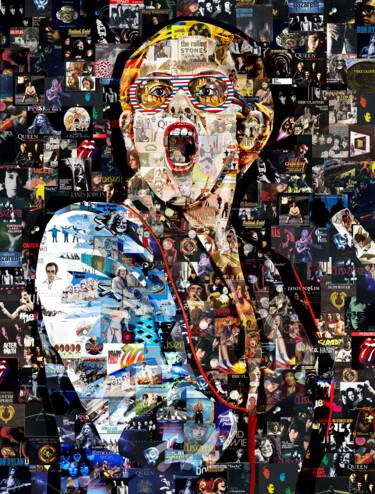

My top ten paintings relate art and music in the way the former of these two forms of expression approaches the latter, immortalizing and making concrete its intangible sound. In fact, it was probably painting that first approached the abstract world of notes, initially through a realism aimed at capturing musical instruments and musicians and, later, by untying itself from the more obvious real datum, just as the example of Kandinsky and Klee taught us. The first of these two masters gave his works names related to music, focusing his work on the balances and tensions between colors, giving rise to chords of different tones, explicitly declaring that painting could develop precisely the powers of music. About the second, however, he, also a musician, was inspired by sound to shape techniques developed through his pictorial investigation. This exaltation of the role of painting, to be understood as a means of rendering the ephemeral art of music par excellence, should not, however, lose sight of how sound, in turn, also inspired the language of the brush, through the more abstract forms of its vocabulary, something that can be seen, for example, in the activity of James McNeill Whistler, a painter who titled many of his works with musical terms. In addition to the latter, artist PJ Crook also looked at music, designing a series of unforgettable album covers that perfectly matched the extravagant and exploratory notes of the band King Crimson.

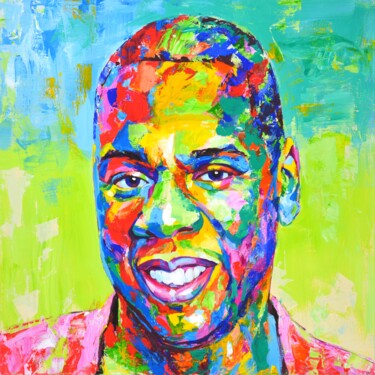

KATY PERRY (2021)Painting by Iryna Kastsova.

KATY PERRY (2021)Painting by Iryna Kastsova.

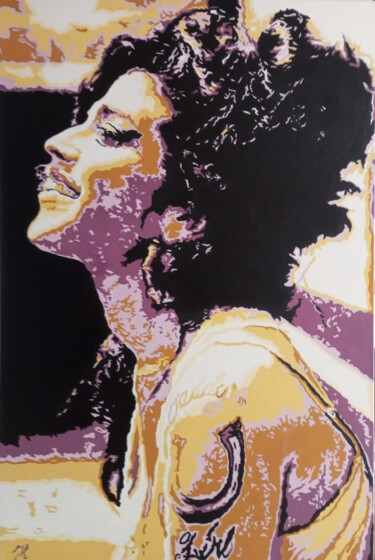

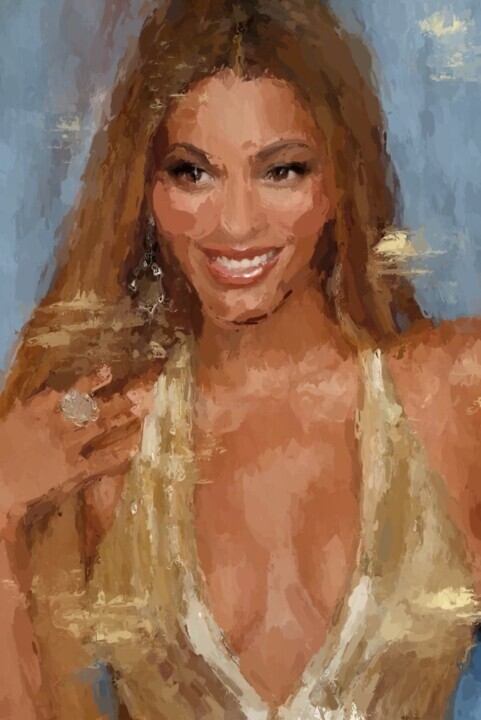

BEYONCÉ, ORIGINAL PAINTING, BEAUTIFUL CELEBRATE SINGER (2023)Painting by Marina Fedorova.

BEYONCÉ, ORIGINAL PAINTING, BEAUTIFUL CELEBRATE SINGER (2023)Painting by Marina Fedorova.

Shifting, as well as continuing, that discourse into the nearer present day, after viewing Artmajeur's artworks depicting Lady Gaga, Beyonce and Katy Perry, much like those executed by Iryna Kastsova, Marina Fedorova and Sobalvarro, it occurred to me how these three singers have sometimes actually moved from the world of music to the world of visual arts. In fact, the first star has collaborated with Jeff Koons, embarked on the "Abramovic method" by recreating the iconic artist's past performances, and has been portrayed by artist-photographer Robert Wilson as some of the most famous figures in the Louvre's collection. As for Beyonce, on the other hand, the singer is known to masterfully mix art-historical references in her videos, magazines and album covers, in a look designed to enhance her image as an assertive goddess. This form of hybridization between the arts stems from the family context in which the artist grew up, where she was encouraged by her mother to reflect on herself through the use of positive, noble and strong images from African, African American and more generally female iconography. Ending with Kety, she has the distinction of having collaborated with painter Will Cotton to design the video California Gurls and with sculptor Urs Fischer, a Swiss artist whom she involved in the promotion of her album Witness, spurring him to create a plasticine sculpture refracting Perry herself. Finally, after publicizing even the less popular references to art by the music world, I return to my top 10, aimed at illuistrating how the most popular painters of all time have captured musicians, sheet music, and musical instruments.

Top 10: paintings of musicians

Édouard Manet, The Fifer, 1866. Oil on canvas, 160×98 cm. Museo d'Orsay, Parigi.

Édouard Manet, The Fifer, 1866. Oil on canvas, 160×98 cm. Museo d'Orsay, Parigi.

10. The Fifer (1866) by Édouard Manet

Against a neutral and empty background, in which the floor is almost indistinguishable from the upper part of the support, depicting, perhaps, the wall of an interior, is placed the figure of a young piper, who, from his clothing, is inferred to be stationed with the Imperial Guard, a peculiarity that leads one to think that such a model was procured for the artist by Commander Lejsne, although some critics have entertained the hypothesis that he is Léon-Édouard Koëlla, the alleged son of Manet and Suzanne Leenhoff. In spite of these chatty identifying suppositions, what is really important is the manner in which the aforementioned subject is treated, aimed at making explicit the French master's intention to transcend the canons of figure painting through the elaboration of a simplified language, which, at the time, was perceived as somewhat provocative in its mode of rendering forms, given by the juxtaposition of two-dimensional backgrounds. Finally, returning to the effigy, it is important, more than his identity, to emphasize how he is a figure of clear Hispanic inspiration, a country to which Manet also began to look for inspiration from the works housed at the Prado Museum in Madrid, a place where he especially admired the work of Velázquez, being particularly impressed by the masterpiece titled Pablo de Valladolid.

Edgar Degas, The Orchestra of the Opéra, 1868. Oil on canvas, 56,5×46 cm. Museo d'Orsay, Paris.

Edgar Degas, The Orchestra of the Opéra, 1868. Oil on canvas, 56,5×46 cm. Museo d'Orsay, Paris.

9. The Orchestra of the Opéra (1868) by Edgar Degas

The perspective cut of the masterpiece in question, aimed at "decapitating" the upper part of the dancers' bodies, portrayed in order to make us understand where we are, while focusing attention on the subject of the orchestra, seems to have been borrowed from the newly born photographic art, a technique that Degas used as a source of inspiration for many of his paintings, also experimenting with a familiar and extemporaneous relationship. Returning to the masterpiece in question, L'orchestre de l'Operà mainly depicts some of the musicians of the famous Paris theater, placing at the center the portrait of an oboe player, who is surrounded by other instrumentalists, who are observed, in an almost eerie way, by a lone figure in the background, portrayed inside a side stage. It is important to point out that the above-described approach to the subject matter was somewhat novel and unconventional for the time, as in the paintings of the same age the subject investigated was generally that of the stage, while there are in fact few depictions of the orchestra, which can be found in the work of Doré and Daumier. Moreover, we do not know whether the choice of such a subject was favored by the fact that the aforementioned musicians were actually acquaintances of Degas, so much so that among them are composer Emmanuel Chabrier and oboist Désiré Dihau, who lived right next door to the painter's atelier once he was back from Italy.

8. Man with Violin by George Braque

A somewhat confused view of forms, within which only the chiaroscuros appear with clarity, aimed at originating, as the title necessarily makes clear, the figure of a man with violin, a subject rendered through Braque's most typical Cubist optics, capable of rendering effigies through the juxtaposition of decomposed forms, which, in this case, take on the appearance of a stringed musical instrument, whose presence is intuitable in the lower, illuminated part of the support. The intent of this peculiar point of view on reality is surely to go beyond the more traditional geometric design of the image, favoring a description of forms that goes beyond mere observation, stimulating the viewer to imagine things never before perceived. This conception of art accepts a component of abstraction, whose main interest is realized in the figurative decomposition, aimed at becoming a precise statement of aesthetic ideal, in which the man and the violin are identifiable very hardly and, certainly, by means of few details capable of guiding the deciphering of forms.

7. Piano Lesson (1916) by Herni Matisse

Unlike most of the masterpieces in the history of art, designed to reveal the relationship between man and music through the more popular depiction of the sinuous movement in succession of the hands of the effigies, turning their "caresses" on a specific musical instrument, Matisse's masterpiece conceals, behind a score, this recurring vision of tactile encounter. I am talking about Piano Lesson, a 1916 painting by the French master, in which the event indicated by the title itself is captured, which, taking place in the living room of the painter's house in Issy-les-Moulineaux, captures the artist's youngest son, namely Pierre, while he is intent on practicing on the aforementioned instrument, surrounded by the sculpture made by his father, titled Decorative Figure (1908) and positioned at the bottom left of the support, and the painting by the same author, depicting a woman on a stool. Everything is narrated by means of naturalistic stylistic features that are prograssively abandoned, as they are deprived of details and enriched with wide backgrounds of "abstract" color, having the purpose of evoking that precise instant, in which light suddenly reveals itself in an interior, taking shape in the green triangle located near the French windows door, as well as in the same geometric figure that appears on the face of the young protagonist of the work.

Amedeo Modigliani, The Cellist, 1909. Oil on canvas, 73,5×59,5 cm. Private collection.

Amedeo Modigliani, The Cellist, 1909. Oil on canvas, 73,5×59,5 cm. Private collection.

6. The Cellist (1909) by Amedeo Modigliani

Before analyzing The Cellist, it is good to make clear some key points of the figurative investigation, with regard to the genre of the portrait, carried out by the Italian master in question, a typical drug-addicted and alcoholic cursed painter, who understood the human subject as a concrete possibility of interweaving relational exchanges, aimed at giving voice to an intrusive talent ready to capture the most intimate aspects of the effigy, revealing them in a sort of inner mirror. For this reason, in most cases, the artist captures his subjects frontally, highlighting their features and their often blind eyes. In the case of The Cellist, however, the elusive perspective with which the protagonist's face is captured deprives us of a careful externalization of his inner self, which is captured, rather, in the intimate relationship he has with his instrument. In addition, The Cellist is also one of Amedeo's few masterpieces in which the subject is caught up in something else, as he is extremely concentrated in the execution of an action, rather than being a static model waiting to be portrayed.

Marc Chagall, The Fiddler, 1913. Painting, 188 × 158cm. Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

5. The Fiddler (1913) by Marc Chagall

March Chagall's "musical portrait" goes beyond the mere depiction of an educated personage while intent on playing music, as it also represents a clear evocation of the cultural heritage of the painter's homeland, which is nostalgically recalled, both by the likeness of the aforementioned player and the rustic village in which he labors to practice. Adding to the above are also Chagall's religious beliefs, which, referring to the figure of the Chabad Hasidim, recognize music and dance as a means of attaining communion with God, so much so that the violinist himself was considered to be a necessary presence within ceremonies and festivals. Although the painting in question reflects the proximity of its creator to his native country, it was completed in 1913, that is, when the painter was in France, a place where he also assimilated some of the Cubist stylistic features, to bring to life the aforementioned depiction, which, set precisely in Vitebsk, summarizes in a single character that battle existing within every average individual, aimed at contrasting the passage of the different life stages.

4. Music I (1895) Gustav Klimt

With Klimt we come to know a type of depiction of music, which, up to this point in the top 10, has been somewhat neglected, namely the allegorical one, rendered through the depiction of two main subjects: a woman holding a lyre and her counterpart, rendered in the guise of a sphinx painted on the right side of the stand, intended to represent that Egyptian mythological creature who, half-woman and half-lion, is able to unite in herself the polarity of the animal and spiritual worlds, as well as those of instinct and reason. As for the lyre player, on the other hand, she, the subject of two other works by the artist, such as a panel published in Ver Sacrum in 1901 and a scene from Beethoven's Frieze, was created as a synthesis of the theories of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Richard Wagner, aimed at identifying music as the superior art, since it is capable, independently of words and images, of transmitting knowledge to man. All this complex narrative is conveyed to the viewer through precise stylistic devices, which concur in mixing figuration and ornament, as well as two-dimensionality and relief, becoming clear manifestos of the artist's youthful style, inextricably marked by Art Nouveau.

Jan Vermeer, The Music Lesson, 1662. Oil on canvas, 74.6 cm × 64.1 cm. Queen's Gallery, London.

Jan Vermeer, The Music Lesson, 1662. Oil on canvas, 74.6 cm × 64.1 cm. Queen's Gallery, London.

3. The Music Lesson (1662) by Jan Vermeer

Before analyzing the masterpiece dated 1662, it is worth explicating how music is a somewhat recurring theme in the work of Vermeer, a painter who interpreted this subject, one of the most iconic in Dutch Golden Age painting, within no fewer than twelve of the thirty-six works of art by his hand currently known. This figurative choice could be linked to the fact that works with a musical theme found a fair amount of success among the artist's clients, who, members of high society, had certainly had musical training. The type of paintings in question were also well-known and sought-after because they often contained mischievous, as well as captivating, references to romantic intrigue, designed to increase the interest held in such depictions. What has just been ascertained would also be reflected in The Music Lesson (1662), a masterpiece in which the mirror reveals how, in fact, the maiden is more interested in observing the gentleman at her side, rather than the piano. Reinforcing these suppositions would also be the Latin motto that appears on the virginal: "music is companion to joy and balm to sorrow," intended to allude, both to the soothing powers of music and to sentimental vicissitudes.

Pablo Picasso, The Old guitarist, 1903. Oil on panel, 122.9 cm × 82.6 cm. Art Institute of Chicago.

2. The Old Guitarist (1903) by Pablo Picasso

It is impossible to talk about the Old Blind Guitarist without referring to the blue period to which the masterpiece itself belongs, which can be traced back to a three-year time span from 1901 to 1904, and which is devoted to externalizing, through art, a profound grief that seized the artist, indelibly marked by the death of his friend Carlos Casagemas, a painter who committed suicide because of his unrequited love for the French model and dancer Germaine Pichot, the protagonist of many of Picasso's canvases. Adding to the nefarious event above are Pablo's economic difficulties, who finds in the color blue a means of atoning for his sadness, captured pricipally in the depiction of outcasts, restless and dramatic subjects. The Old Blind Guitarist fits well into what has just been described, himself presenting an expression of unequivocal drama and suffering, which is countered by his guitar: a musical instrument that represents life and salvation, as art, per se, is always understood as a means of overcoming adversity and seeing visible, again, the beauty of the world.

Caravaggio, The musicians, 1597. Oil on canvas, 87,9×115,9 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Caravaggio, The musicians, 1597. Oil on canvas, 87,9×115,9 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

1. The Musicians (1597) by Caravaggio

The oil on canvas by the Italian master makes concrete on the pictorial support the vision of a pagan allegory, aimed to take shape in the likenesses of three young musicians dressed in the old-fashioned way, who find their place in a cramped environment. What is described seems difficult from being interpreted in an erotic key, although this would be possible, as the presence of the figure of the winged cupid, who is intent on plucking a bunch of grapes, would seem to indicate a reunion of an intimate nature, aimed at erupting into an amorous passion, typical of the ambiguity of Caravaggio's early works. The eroticism in question is brought to life by the bodies of idealized young people, with rather delicate and refined faces, in which only the character playing the cornet, arranged in the center, would seem to be ascribable to the genre of the portrait, and precisely of the self-portrait, so much so that it could depict the young Caravaggio himself, given the affinity that the latter presents with other contemporary paintings, in which the painter had captured his own features. As for the clothing, on the other hand, it is not at all strange that the master made reference to antiquity, since at the time young musicians dressed in the classical style, that is, as Eros, Bacchus, or angelic singers, just as might have been the case during the performances beloved by the painter's greatest patron: cardinal del Monte. Finally, within the great Italian art-historical tradition, it is worth highlighting how painters of the caliber of Giorgione and Titian generally used to arrange musical subjects in outdoor, pastoral and allegorical settings, while Caravaggio shifted the theme to an interior, innovatively bringing together portraits captured from the natural and allegorical depictions.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli