Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880-1881. Oil on canvas, 129.9 cm × 172.7 cm. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880-1881. Oil on canvas, 129.9 cm × 172.7 cm. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

Impressionism in a Nutshell

How did Impressionism come into being? Like all things, it started with an idea! The artists in question decided to paint the reality around them in a very simple way, leaving aside the more complex and well-trodden historical and mythological subjects, themes that often tended to be associated with a certain pursuit of perfection in visual and therefore executive appearance. Now what mattered, as suggested by the name of the artistic movement born in France around 1860, was the rendering of the impression, or how a landscape, but also an object and a person, appeared to the eye in a limited span of time. In order to make this purpose effective, the way color was applied to the support changed drastically: brushstrokes were now lighter, freer, and the colors more muted, born from execution exclusively en plein air. It was evident from outdoor observation that what the eye perceived was indeed different from what the brain understood, so that by capturing the optical effects of the moment, one moved away definitively from idealized forms and perfect symmetry, giving voice to the world as actually seen by our gaze. In fact, three-dimensional perspective was also silenced, a technical fact that led Impressionism to cease distinguishing the most important elements of a composition from those of lesser significance. All these characteristics turned into criticisms from the academic tradition of the time, which, however, could no longer stop the advance of modern art, as well as the entire philosophy associated with the avant-garde.

Édouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass, 1863. Oil on canvas, 208×264 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Édouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass, 1863. Oil on canvas, 208×264 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Édouard Manet: Luncheon on the Grass (1863)

The work of Édouard Manet, a French painter bridging the gap between Realism and Impressionism, was heavily criticized by his contemporary audience, who were quite disoriented to see glimpses of real life realized on the canvas, in which, at times, even people on the margins of society took shape, treated in the same way as characters from more traditional historical and mythological works. To the above was added the suspicion reserved for his peculiar style, which, anticipating Impressionism, lacked both chiaroscuro and shading, as it juxtaposed patches of color, which, only when viewed from the right distance, generated the shapes envisioned by the artist. Finally, to talk about the master whom many recognize as the father of Impressionism, I have chosen to describe Luncheon on the Grass, a masterpiece from 1863, which deeply scandalized the Salon des Refusés audience, as it presented not only a seated nude woman flanked by two dressed men but also a summary painting technique, regarding the description of forms and background. In addition, the depth of space was innovatively rendered without resorting to traditional perspective, but through suggestions made up of juxtaposed spots of different colors. It is precisely what is represented in this work that would pave the way for what we will see in this top 10: the most important masterpieces of Impressionism!

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1874. Oil on canvas, 48 cm × 63 cm. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris.

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1874. Oil on canvas, 48 cm × 63 cm. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris.

Claude Monet: Impression, Sunrise (1874)

Here is another masterpiece that is not only painting but also tangible history of the Impressionist movement, as Impression, Sunrise was exhibited in 1874 at the former studio of the photographer Nadar, suggesting, with its title, the name of the entire artistic movement. The painting in question, created en plein air to capture what the master saw from the window of his hotel room in Le Havre, reproduces the morning view of the harbor, with the sea traversed by some boats and the horizon showing the industrial life of the urban context. What is described already has all the characteristics dear to the more mature Impressionism, so much so that the view is rendered through juxtaposed, fast, and free brushstrokes, ready to shape all the elements of the composition. In fact, it is only by observing the whole that we can fully understand the nature of the subjects immortalized, which, if taken one by one, almost lose their identity. This makes us understand the artist's real intentions, which were no longer to create a naturalistic scene, but to evoke it through environmental suggestions. Finally, it is good to reveal a secret, that is, what practically allowed Monet to execute the aforementioned masterpiece? So, it is necessary to reveal how the practice of outdoor painting, typically Impressionist, was made possible by the invention in 1841 by John Rand, who created metal tubes to preserve oil colors, which from that moment on could be easily transported anywhere!

Edgar Degas, The Dance Class, 1873-1876. Oil paint on canvas, 83.5 by 77.2 centimetres. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Edgar Degas, The Dance Class, 1873-1876. Oil paint on canvas, 83.5 by 77.2 centimetres. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

Edgar Degas: The Dance Class (1873-1876)

Before discussing the masterpiece at hand, it's important to clarify the identity of the painter who, initially closer to Realism, approached the subjects of modern life in Impressionism from the 1870s onwards, despite always staying away from en plein air painting and the elimination of contour lines. Now that we have clarified what makes the French master an atypical Impressionist, we can move on to the description of one of his most famous canvases: The Dance Class. Even though it was created in the studio, it appears as if created in one go to immortalize the dance foyer of the Paris Opéra, where the artist could gain access through the intercession of his friend, the orchestra conductor. From this privileged place, the painter captured a young ballerina practicing steps under the watchful eye of the famous choreographer Jules Perrot. As for the other girls in tutus, they take advantage of the break to rest, perhaps chat quietly, and adjust their clothing. Everything seems extremely spontaneous and natural because Degas gives new importance to everyday life, sometimes reproducing it with an almost obsessive attention, always ready to synthesize attitudes and behaviors in the most authentic way of being in situations.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880-1881. Oil on canvas, 129.9 cm × 172.7 cm. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1880-1881. Oil on canvas, 129.9 cm × 172.7 cm. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880-1881)

Like Monet, Renoir is a true Impressionist, the author of one of the most famous masterpieces of the artistic movement of our interest, namely: Luncheon of the Boating Party, a canvas from around 1880 in which he depicts friends and acquaintances expertly directed, almost as if on a film set. All this makes up a scene in which, under an awning, rowers and other figures gather around a table, on which it is implied that a meal has just been consumed. The subjects now think about conversing, enjoying the atmosphere of a warm afternoon spent on the Seine, a river that, as seen in the upper left, literally makes its way through the plants, crossed by some boats. However, those mostly highlighted, as they are in the foreground, are a girl playing with a little dog, observed by a rower, and another rower resting against the balustrade on the left. In addition, always close to the viewer, there are also two young people sitting at the table, who have their backs to the noisier figures in the background. Once again, the texture of the painting is made up of broad material brushstrokes, ready to blur the outlines of the forms, whose details are hinted at but not described.

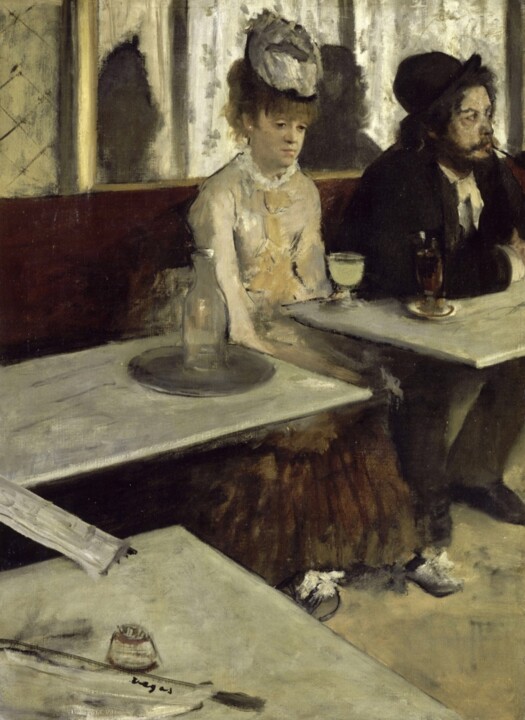

Edgar Degas, Dans un café, 1875-1876. Oil on canvas, 92×68 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Edgar Degas, Dans un café, 1875-1876. Oil on canvas, 92×68 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Edgar Degas: Dans un café (1875-1876)

Here's Degas, yes, him again! After all, it was impossible not to include his Absinthe Drinkers in the ranking, a work that, in addition to documenting a sad reality of the time, was inspired by Émile Zola's novel "L'Assommoir," of which the painter saw some previews. In fact, the writer confessed to the artist how he had talked about the degraded condition in which the Parisian proletariat was living, well personified in the masterpiece by two friends of Degas. However, once the painting was completed, these two individuals complained about how it could damage their reputation, so the painter decided to publicly declare that the two figures were not really alcoholics. In the work, however, the two patrons are seated at café tables, on which alcoholic beverages are placed, even though those depicted seem to almost leave them there, perhaps because, already drunk, they appear to be taken by more profound thoughts, projecting their gazes directly into emptiness. How about a cocktail tonight?

Claude Monet, Water Lily Pond, Pink Harmony, 1900. Olio su tela, 89,5×100 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Parigi.

Claude Monet, Water Lily Pond, Pink Harmony, 1900. Olio su tela, 89,5×100 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Parigi.

Claude Monet: Water Lily Pond, Pink Harmony (1900)

It was impossible not to refer again to the most popular of the Impressionists, undoubtedly Claude Monet, the author of the famous Water Lily Pond, Pink Harmony, dated 1900. In this work, the imposing figure of an arched bridge appears before the viewer, ready to cross a pond of water lilies. The whole scene is illuminated by the rays of the sun, carefully penetrating every leaf, while the flowers reveal their predominant color: pink! In the foreground, we find the shore, characterized by the presence of dense and tall vegetation, which, in some places, merges with the hanging leaves of the willow trees. Once again, it speaks of the light filtering through, creating areas of shadow and areas of light, ready to create a rich alternation of shades that extend over the water and the shores. Where is the subject of Monet's landscape? In Giverny, in the artist's residence, where he personally took care of the various plants in the garden, which he wanted to transform into a green theater, always ready to become the subject of his art, where he also had the above-mentioned Japanese-style bridge built.

Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1877. Oil on canvas, 212.2 cm × 276.2 cm . The art Institute of Chicago, USA.

Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1877. Oil on canvas, 212.2 cm × 276.2 cm . The art Institute of Chicago, USA.

Gustave Caillebotte: Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877)

Gustave Caillebotte's Paris Street; Rainy Day tells and documents the restructuring of the French capital, which took place at the end of the 19th century according to the project of Georges-Eugène Haussmann, ready to manifest itself in the depiction of a large intersection near the Saint-Lazare station, which replaced an older hilly area with narrow, winding streets and dilapidated buildings. This new face of Paris is traversed by the main subjects of the work, a couple of passersby walking arm in arm, sheltering from the rain under an umbrella and crossing paths with another passerby, who finds a place next to the facade of a building on the right. On the left, other people walk, also equipped with umbrellas, gradually avoiding some carriages, which find their reason for being under the presence of large buildings, probably ready to be reflected in the multiple reflections created by the wet stone block pavement. Certainly, these last ones take on the color of the cloudy sky, whose horizon is dominated by the presence of a larger corner building, which appears isolated in the center of the scene. Finally, certainly worth noting is another, but silent, protagonist of the painting: I'm talking about the green lamppost that stands silently behind the figures of the two main subjects.

Mary Cassatt, The Boating Party, 1893. Oil on canvas, 90 cm × 117.3 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Mary Cassatt, The Boating Party, 1893. Oil on canvas, 90 cm × 117.3 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Mary Cassatt: The Boating Party (1893)

Can we talk about Impressionism without celebrating its most illustrious women? I would say absolutely not, so I hasten to mention Mary Cassatt, an American painter and printmaker born in 1844, the author of The Boating Party. This masterpiece, created in Antibes (French Riviera, France), depicts a woman, a child, and a man on a sailboat without a mast but with a canoe-like hull and three seats, an environment rendered with the use of yellow color, which stands out against the darker and wider blue of the sea. In fact, Cassatt uses both bold and more shadowy colors to generate contrasts, which reach their peak in the comparison between the vibrant boat and the blue figure of the rower. Despite the treatment of colors, which aims to fit into the artist's usual style, what differs is the theme of the work, which, while including the familiar one of mother and child, also includes, in the unusual space of the boat, the male figure, often overlooked by the painter. In any case, the roles within the masterpiece seem to be firmly established, so much so that the man focuses exclusively on work (now rowing), and the woman constantly watches over the child. Following this interpretation is the idea of seeing the oar as a dividing line between the male and female worlds, the second of which is indissolubly associated by the artist with nature, creativity, and renewal, realms in which the importance of the mother's role within society is undisputed.

Berthe Morisot, The Cradle, 1872. Oil on canvas, 56 cm × 46 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Berthe Morisot, The Cradle, 1872. Oil on canvas, 56 cm × 46 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Berthe Morisot: The Cradle (1872)

Berthe Morisot was a French Impressionist painter, known for being one of the founders of the movement, as well as the creator of multiple masterpieces in art history, such as The Cradle. This painting, dated 1872 and exhibited at the first Impressionist exhibition held two years later, depicts a young woman in profile, sitting next to a cradle in which a baby is sleeping. The mother is not just a model but one of the artist's two sisters, Edma, immortalized with Berthe's niece, the little Blanche. This double portrait was conceived to consciously address the theme of motherhood, one of the painter's favorite subjects, who enjoyed depicting intimate scenes that always revealed the existing bond of love, especially between mothers and daughters. To make this eternal connection explicit are also the small details in the composition, such as the faces of the two protagonists, connected by a compositional diagonal, as well as the mother's gesture of protecting the little one, both with her gaze and with a veil, and finally, the fact that both subjects have their arms bent.

Claude Monet: Woman with a Parasol - Madame Monet and Her Son, 1875. Oil Canvas, 100 cm × 81 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Claude Monet: Woman with a Parasol - Madame Monet and Her Son, 1875. Oil Canvas, 100 cm × 81 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Claude Monet: Woman with a Parasol - Madame Monet and Her Son (1875)

Help, I can't stop bringing up Monet, but then again, would you dare not to talk excessively about him while discussing the most famous masterpieces of Impressionism? Personally, I have decided to conclude my ranking with one of the most well-known paintings by the most famous of the Impressionists: Woman with a Parasol - Madame Monet and Her Son (1875)! This work, along with its "counterpart" Woman with a Parasol - Madame Monet and Her Son, is kept at the Musée d'Orsay and stands out for the theme it explores. In fact, the French painter was quite renowned for his landscapes, certainly more favored than the exaltation of the human figure, which, in this case, takes the form of Suzanne Hoschedé, the wife of the American Impressionist painter Theodore Earl Butler. The interest in this particular subject arose in a specific context: the master was observing Suzanne as she climbed a hill on Île aux Orties, a place and situation where interesting plays of light were reproducing on the girl's dress. This very vision gave birth to a painting featuring a figure in typical bourgeois clothing of the time, seeking shade from the sun with an umbrella while immersed in a bucolic landscape, in which nature appears lush. Finally, the artist makes it all the more special by giving it a peculiar monumentality, achieved through a low perspective, ready to elevate the image of Hoschedé, whose face, only "outlined," is in shadow, just like most of her body captured from behind.

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli

Olimpia Gaia Martinelli